Faith

The pastoral implications of SC (37-40) are very evident in the treatment of the cultural adaptation of the liturgy (later to be called "inculturation"), perhaps the most adventurous section in the document.

SJ

Another important principle for reform that was to have enormous pastoral consequences was the desire to enrich the liturgy's use of Scripture, expressed in a general mandate to broaden the use of the Bible. (Sacrosanctum Concilium 24) Further, in order to show the connection between actions and words in the liturgy, SC 35.1 states: "In sacred celebrations a more ample, more varied, and more suitable reading from Sacred Scripture should be restored." With regard to the Eucharist, the constitution is even clearer: "The treasures of the Bible are to be opened up more lavishly, so that richer fare may be provided for the faithful at the table of God's word. In this way a more representative portion of the holy scriptures will be read to the people in the course of a prescribed number of years." (SC 51) Eventually, this mandate led to a three-year Sunday cycle of readings that included the Old Testament for the first time during most of the liturgical cycle as well as a two-year cycle of weekday readings. A similar recommendation to increase the amount of Scripture is made with regard to the Liturgy of the Hours (SC 92).

The exact nature of the reform to be undertaken provides for a fourth pastoral principle. Here, the constitution requires distinguishing between "unchangeable elements of the liturgy divinely instituted and a judgment regarding liturgical developments out of harmony with the nature of liturgy itself so that the rites might themselves be able to communicate more clearly 'the holy things, which they signify.'" (SC 21) Moreover, the document stresses that the revision of these elements is to proceed with caution on the basis of historical, theological, and pastoral study. The most delicate formulation comes at the end of SC 23: "Finally, there must be no innovations unless the good of the Church genuinely and certainly requires them; and care must be taken that any new forms adopted should in some way grow organically from forms already existing." Precisely what constitutes "organic" development was to become a bone of contention in the post-conciliar reform.

Another principle that was contended after the council had to do with the presentation of the rites: "The rites should be distinguished by a noble simplicity. They should be short, clear, and free from useless repetitions. They should be within the people's powers of comprehension, and normally should not require much explanation." (SC 34) Critics labeled this approach to liturgical reform "modernist" and criticized for being based on a naÏve and outdated anthropology that did not take into account the complex nature of ritual.

The pastoral implications of SC (37-40) are very evident in the treatment of the cultural adaptation of the liturgy (later to be called "inculturation"), perhaps the most adventurous section in the document. In light of the church's sharp rejection of liturgical adaptation in China and India in the 17th century, this section of the constitution is indeed revolutionary. A "rigid uniformity" (37) of the rites is to be avoided and "legitimate variations" (38) permitted, and "(i)n some places and circumstances, however, an even more radical adaptation is needed." (40) Those more radical adaptations needed to be approved by the territorial episcopal conferences but the radical adaptations in consultation with the Vatican.

It is hard to imagine that the celebration of the Eucharist in the rites of the various churches in union with Rome (e.g. Melkite, Ethiopic, Syrian, Byzantine) at the beginning of many daily sessions did not open the eyes of the council fathers to the historical reality of "legitimate variations" in the worship of the church.

Finally, and more of a pastoral strategy than a principle, attention is given to liturgical education and formation. In the first place, centers for training liturgical professors are to be established (SC 15). In addition, the study of liturgy in its various aspects (historical, pastoral, theological, juridical) is to be made a compulsory subject in seminaries, and seminarians are to be formed spiritually in the liturgy as well. (SC 16-17) Those already ordained are to be educated in the liturgy so as to serve and form their people. (SC 18-19) Moreover, national and diocesan liturgical commissions are to be established to implement the liturgical reform set in motion by the council. (SC 44)

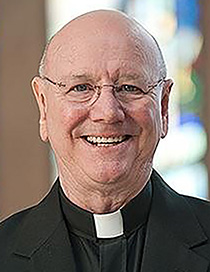

- Father John F. Baldovin, SJ, is professor of Historical and Liturgical Theology at Boston College School of Theology and Ministry.

Recent articles in the Faith & Family section

-

7 reasons to pray for the cardinals in conclaveJaymie Stuart Wolfe

-

Legacies in Ordinary TimeLucia A. Silecchia

-

What are my Easter duties?Jenna Marie Cooper

-

On the Camino: Jentillaks and jazzMark T. Valley

-

From the Eternal CityArchbishop Richard G. Henning