O’Reilly recalled in night of song and poetry

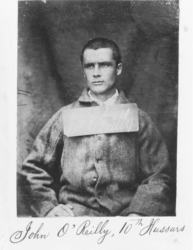

Though John Boyle O’Reilly has been gone for more than 100 years, the story and verse of the legendary Irish poet and Pilot editor came to life again for one recent night in Boston.

The Eire Society of Boston and the Irish-American Cultural Institute hosted singer Sean Tyrrell performing “Cry of the Dreamer: The Amazing Story of Irish Hero John Boyle O’Reilly” Oct. 13 at Copley Square’s Park Plaza Hotel.

Tyrrell, a native of Galway, said he was living in the Bronx in the late 1960s where he was playing with other Irish musicians, when he first encountered O’Reilly’s writing.

It was in a used bookstore where he discovered a copy of “1,000 Years of Irish Poetry,” which included the poem “A Message of Peace,” he said. “I was totally amazed by the contents and the style.”

Over the years, he continued to delve into the poems and the life of the man who wrote them, he said.

Putting the poems to music, Tyrrell said he released a 1994 album, “Cry of the Dreamer,” a title taken from one of the three poems that he included on the album, along with “A Message of Peace” and “Only from Day to Day.” Those songs and others, along with the narrative of O’Reilly’s life, became the 90-minute one-man show he now performs.

The poem, “Cry of the Dreamer,” with the lines: ‘‘From the sleepless thoughts’ endeavor/I would go where the children play/For a dreamer lives forever/And a thinker dies in a day,’’ was written by O’Reilly and inspired by his seeing a cloud-cast Ireland for the last time aboard the American ship “The Bombay” on passage from Liverpool to Philadelphia in 1870, Tyrrell said.

Upon landing in Philadelphia O’Reilly made his way to Boston, where he became the editor and then part owner of The Pilot, which was then in private hands. O’Reilly remained with the paper until he died at his home in Hull in 1890 at age 46, Tyrrell explained.

O’Reilly’s first assignment for The Pilot was to cover the convention in New York City of an Irish revolutionary group, the Feinians, he said. It was a group the poet knew well. It was as a member of the group in Ireland that O’Reilly began his journey.

O’Reilly and a cadre of Feinians realized that one-third of the British Army was made up of Irish soldiers, so they joined themselves with the intent of politicizing their countrymen-in-arms and taking over regiments from within, he said.

In O’Reilly’s own regiment he had commitments from 80 of the 100 soldiers, including non-Irish soldiers, Tyrrell said.

But, before the plot could be executed, an Irish soldier named Foley turned in the conspirators.

“It was not the first time an Irish rebellion was sold out by one of its own,” he said.

Tyrell added that it was a testimony of O’Reilly’s character that when he encountered his betrayer years later, penniless and asking for help, O’Reilly gave him money, clothes and his good wishes.

O’Reilly was at first sentenced to death for treason, but the sentence was commuted to hard labor in a series of prisons. Ultimately, he found himself a member of a labor gang building roads in Western Australia, Tyrell said.

When O’Reilly landed in Freemantle, Australia a guard called him out: “Number 9843, you Feinian bastard! You know why you are here and I will not let you forget it,” he said.

To which O’Reilly replied, “Once I was an English soldier. Now, I am an English felon and I am proud of the exchange.”

When he told the prison chaplain his intention to escape, the priest agreed to help him, as long as he promised not to attempt a break into the wilderness by himself, he said. O’Reilly agreed.

After the priest arranged for an American whaling ship, Vigilant, to pick O’Reilly up, the young man bolted for the beach and a waiting rowboat, he said.

Waiting in the boat, O’Reilly watched as the Vigilant sailed passed him and he had to return to the beach, where he hid out until the priest could arrange for another attempt. Two weeks later, he was picked up by another American ship, the Gazelle, he said.

Years after his own escape, Tyrrell said O’Reilly received a letter from his comrades begging him to not let them be forgotten. Moved by the plea, the poet raised $20,000 to hire a New Bedford whaling boat, the Catalpa, and make the rescue.

Once in Australia, an agent of O’Reilly’s, posing as a rich American businessman, went ashore to make arraignments for the escape. Meanwhile, the Catalpa sat anchored out at sea.

After a number of delays, the right moment arrived. The Fienians broke from work parties for waiting wagons, which took them to the small boat waiting on the beach that they rowed through a storm and heavy seas until they were picked up by the Catalpa.

Tyrell said the escape was remarkable because the British, in their bigotry toward the Irish temperament, assumed any rescue would come in the form of a warship and an armed landing party making an assault on the prison.

What was even more remarkable, was that though nearly 5,000 Irish supporters and donors were aware of the plot, not one revealed the scheme to the British, he added.

Back in Boston, O’Reilly continued to publish collections of poetry and became one of the country’s best known Irishmen, he said. O’Reilly sparred with boxer John L. Sullivan and taught fencing at Harvard. He was friend to Mark Twain and President Grover Cleveland, and when the Statue of Liberty was dedicated in 1886, Joseph Pulitzer commissioned him to write a poem for the occasion.

When Oscar Wilde came to America on his speaking tours, he was often introduced by his friend O’Reilly, he said.

As his own reputation grew, O’Reilly embarked on his own national speaking tours, Tyrell said. In 1890, he completed his most successful tour where he lectured on Irish Art and Literature, and drawing audiences of three or four thousand. He returned home exhausted and overwrought by anxiety.

Since the birth of their second of four children, O’Reilly’s wife, Mary, was under the constant care of doctors for dubious ailments, and was regularly prescribed tranquilizers, Tyrrell said.

Soon after returning from this last speaking tour, O’Reilly went to the drugstore to pick up his wife’s medicine. The chemist purportedly noticed his hands shaking and told him, “John, you should take some of this yourself.”

That night, Mary awoke realizing that O’Reilly was not in bed, he said. She went downstairs and found O’Reilly sitting in a chair in the living room with a book. A lit cigarette sat in the ashtray.

“John, why don’t you come to bed?” Tyrrell said Mary asked him.

“Mary, I have just taken some sleeping potion. I think I will just sleep here on the sofa,” O’Reilly reportedly replied.

Tyrrell said Mary did not like the look on her husband’s face and she ran out to get help.

“For two hours, two doctors worked on him, but there was nothing they could do,” he said. O’Reilly died due to an apparent overdose.

The death was ruled an accident, but it could have been medical malpractice, since the chemist did not give O’Reilly proper dosage instructions, he said.

The performance ended, but the night did not. Although, Tyrrell left the room and turned a corner, out of the sight of the audience members as they filed out, he soon joined them at a private section at M.J. Connors, an Irish pub on the hotel’s ground floor.

In some places, pondering the tragic ending of a glorious life would cast a pall over the room. But, with the members of the Eire Society, some of whom brought their own O’Reilly collectibles and mementos to the event, it was it more a celebration and an excuse to tell one more story.