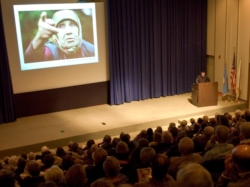

French priest speaks on search for graves of Nazi victims

A French priest described his eight-year quest searching for the lost mass graves of Nazi victims in Ukraine through the testimony of the elderly peasants who witnessed the atrocities to a Boston Public Library audience Sept 25.

“As a boy, I asked my grandfather what it was like inside the camps. He told me in the camps it was awful, but, outside the camps it was worse,” said Father Patrick Desbois, the secretary to the French Conference of Bishops for relations with the Jewish community and an advisor to the Vatican on Judaism.

This short answer was all he ever learned about his grandfather’s deportation from France to the Rawa Ruska camp in Ukraine, but his curiosity has led him to discover 850 sites where Nazis buried the Jews they murdered between 1941 and 1944 in the countryside of Ukraine, he said. It is estimated the Germans killed 1.5 million Ukrainian Jews.

Because the Nazis allotted one bullet for each execution, the priest said he compared the number of cartridges with the bodies he finds. Due to the Germans’ strict one-to-one ratio, many of the victims were not dead when they were put into the earth. “The villagers tell me how the dirt moved because the people were still alive.”

The project began in 2001 with the support of the Archbishop in Paris, the late Cardinal Jean-Marie Lustiger, a convert from Judaism whose own mother was killed in the concentration camps, he said. Since then he has partnered with the U.S. Holocaust Museum in Washington, which provides the priest with funding support and access to its 5 million pages worth of archives from Soviet-led investigations after the end of the Second World War.

For decades the Soviet Union’s stories of Nazi atrocities in Ukraine were discounted as KGB propaganda, but the priest now finds that those post-war investigations, depositions and trials line up nearly 100 percent with the stories told by the peasants, he said. “It is converging proof.”

The Soviet reports are actually more accurate than the German records, which were often written to impress bureaucrats in Germany, he said.

Using the maps and testimonies from the Soviet archives, he travels into each village in a modest blue minibus and stays until all of the graves are discovered.

The priest said he knocks on doors and speaks to people after Mass. Sometimes the villagers come to him with their stories. “One woman brought her husband to me and told him: You were there. I was there. Now, you must tell the priest what happened.” The man showed the priest where five children of the village were buried.

One mass grave he found contained 5,000 bodies and it was in the middle of the village, he said. “They were not in the forest. The farmers knew they were there. They knew because they saw everything.”

Time is now the enemy, Father Desbois said. Not only are the youngest witnesses in their late 60s, but the sites are now prey to grave robbers, who dig up the remains and plunder jewelry, effects and gold fillings.

When the priest uncovers a grave, he is always accompanied by an Orthodox rabbi, who lights a candle for each body found and who then presides over a proper Jewish burial for the victims.

One grave at a time, he is unmaking what was a continent of extermination, he said.

The priest said his work is undoing the intention of the Nazis. “They lay unknown and unmarked. This is was what the Nazis wanted -- as if they never existed.”

Father Desbois said he is encouraged in his work by the reaction to his new book, “The Holocaust by Bullets: A Priest’s Journey to Uncover the Truth behind the Murder of 1.5 Million Jews” and the media coverage he has received, including NBC Nightly News, Time magazine and The New York Times.

In June, French President Nicolas Sarkozy presented him with his nation’s highest civilian award, the Legion of Honor, which the priest wears as a bright red thread on his lapel. After the ceremony, the president spoke with the priest for 25 minutes asking about his work and expressing his pride that such work was being done by a French priest, he said.