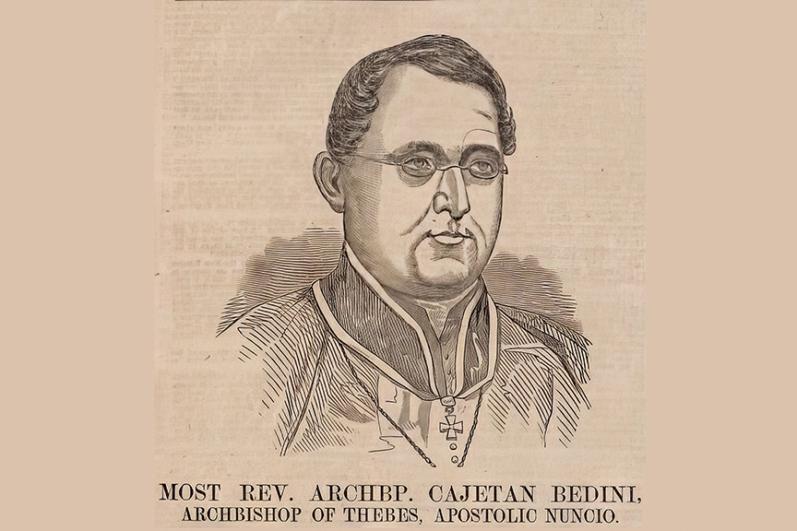

The 1854 visit of Archbishop Gaetano Bedini

On Tuesday, Jan. 31, 1854, Bishop John Fitzpatrick of Boston recorded in his journal "it is supposed in the city that his Excellency Mgr. Bedini Apostolic Nuncio will sail from Boston to-morrow. The sectarian bigots in various parts of the U. States leagued with foreign red-republican refugees from Europe have made it a point to insult him on his passage."

His entry references a visit by Archbishop Gaetano Bedini to the U.S. from June 30, 1853, through Feb. 4, 1854.

Archbishop Bedini was born in Italy on May 15, 1806, and was ordained Dec. 20, 1828, and named to a succession of posts, including Papal Nuncio to Vienna (1838), Apostolic Nuncio to the Imperial Court of Brazil (1846), Secretary of State to the Vatican (1848), Prolegate to Bologna (1849), and Extraordinary Pontifical Commissioner of the four legations of Bologna, Ferrara, Forti, and Ravenna. He was consecrated Titular Archbishop of Thebes and Apostolic Nuncio to Brazil in Rome in May 1852.

While supposedly on his way to Brazil, he first arrived in the U.S. and conducted a fact-finding mission for the Holy See, which wanted to know more about this country, where, over the past years, the Catholic population had grown exponentially and whether it warranted the establishment of an apostolic nunciature in Washington, D.C.

His visit began in Washington, where he delivered a letter from Pope Pius IX to President Franklin Pierce, which was read aloud in the Senate. He then continued to visit cities throughout the country and even passed through Canada before returning to New York City to prepare for his return to Rome around the time of Bishop Fitzpatrick's journal entry of Jan. 31.

A noteworthy aspect of Archbishop Bedini's tour was the anti-Catholic sentiment and public displays to that effect that his presence evoked. It can be attributed to a combination of the notoriously anti-Catholic Nativists or "Know-Nothings," which were near the height of their political influence at the time, and elements of the German and Italian communities who blamed him for the execution of a priest in Bologna while he was stationed there.

Returning to Bishop Fitzpatrick's journal, he noted that riots had taken place in Cincinnati, Wheeling, Baltimore, and New York, and that "the same class of rascals have been preparing for him a similar reception here. But the Nuncio is not with us. The B(isho)p is informed that the rabble intend to circumvent his house to-night."

The next day, he recorded that a mob did indeed come to his home around midnight but, fortunately, was "small and the whole affair a failure." At most, he estimated the crowd to be 200 people, and half of them, he believed, were simply there to watch with curiosity and without "any intention of offering insult or taking part in the spirit of the proceedings."

The crowd "groaned and called for the Butcher Bedini" but after about 45 minutes, they gave up and dispersed without any notable incident. He said there were rumors that before going to his house, the crowd burned the Nuncio in effigy, but, he states, "the report is doubtful" as the police said they did not come across any such activity.

Of the police, he said they were out on the streets in force but did not make any arrests nor identify any of the individuals who composed the mob but, in his words, "winked at the whole matter and perhaps enjoyed the sport as they considered it." It is likely they did not want to escalate a situation that amounted to a harmless demonstration.

Though there was little to report of the previous night, Fitzpatrick records that he was visited by a young German during that day who warned of a group of Germans who were dissatisfied with the result of the previous evening and planned to come again that same night. As a precaution, the bishop notified Mayor Jerome Smith of Boston and the police chief, but there were no further disturbances.

Although these days passed without any incident, Bishop Fitzpatrick felt compelled to write a letter "strictly true in all its statements of the facts" since "none of the Newspapers has denounced the outrage with any degree of boldness."

His letter criticizes the newspapers for the coverage of the events, alleging they "contain many exaggerations, and which appear to him calculated to injure, without just cause, the fair and well-deserved reputation of our city."

He argues that Archbishop Bedini was not burned in effigy as suggested, that the crowd did not exceed 200 in number, much less than reported, and that civil authorities should have done more to prevent the crowd from assembling.

Though, he concludes, he does not pass judgment on those whose job it is to govern and has "neither complaint to make nor defence (sic.) to offer." He simply hopes that he has succeeded in clarifying that no major demonstration took place "by which dishonor or blame can be legitimately attached to the people of Boston."

In his diary he reveals that the letter "conceals the conviction of the writer that many thousands of the inhabitants of Boston, although they sympathize fully with the feelings of the mob and hatred for Catholicity, were deterred by shame and human respect from manifesting this disposition in a public manner."

On the afternoon of Thursday, Feb. 2, the same day he submitted his letter for publication, Bishop Fitzpatrick departed Boston for New York, where Archbishop Bedini was staying as a guest at a private home on Staten Island. The following day, the latter quietly embarked upon a steamer bound Europe, and one day later, the former returned to Boston.

He claims the reason for Archbishop Bedini's quiet departure was due to threats received in retaliation for his alleged involvement in the execution of the priest in Bologna. The following week, The Pilot published a biographical sketch of Msgr. Bedini "merely to narrate a few facts concerning his public career during the last four years." It refutes this story once again, stating at the time the event occurred, Bologna was occupied by the Austrian Army and under martial law. Although he was nominally the Prolegate and Papal Commissioner for Bologna, he and the local justice system were powerless during the occupation. It further notes that following the occupation, he remained in Bologna and was beloved by the people there.

It continues that during his visit to the U.S., a plot to assassinate Archbishop Bedini existed and failed only because one of the conspirators repented and came forward to warn him. The article closes that the event of his visit should mortify Americans and make them aware of the risks "foreign anarchists" pose to the nation.

It concludes "when the country finds that its good name has been seriously compromised in the face of the world by a small clique of refugees who assaulted with murderous intentions an innocent and an inoffensive man, a stranger, a clergyman, and a representative of a friendly Power . . . (the instigators will) have harmed only themselves and, as usual, their actions will turn out to be beneficial to the interests of the Church which they so blindly hate."

Archbishop Bedini did not continue to Brazil as suggested earlier, but returned directly to Rome and delivered a first-hand report on the Catholic Church in the U.S. Although an apostolic delegation would not be established in Washington until 1893, he is said to have inspired the establishment of the Pontifical North American College in Rome, which opened five years later, in 1859.

Reading of this incident today and Bishop Fitzpatrick's writings, there appears to be a clear attempt to name specific elements as the cause for the agitation without calling into question all Bostonians or Americans, even if his private sentiments, believed the majority, harbored anti-Catholic sentiments. This distinction is even more pronounced in The Pilot, which divides these groups into "foreign anarchists" and "Americans."

It is hoped this short feature highlighting Bishop Fitzpatrick's perspective of these events will encourage readers to learn more about the Archbishop Bedini visit to the U.S. and the cultural elements that existed at the time.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.