Escaped Irish rebel Patrick O'Donohoe calls on Bishop Fitzpatrick

On Aug. 2, 1853, Bishop John Bernard Fitzpatrick noted in his journal that "Patrick O'Donahue (sic.), known as one of the Irish patriots of 1848, recently escaped from Australia whither he had been sent by the English government as a convict under sentence of treason and rebellion, calls to see the Bp."

While perhaps forgotten by history, Patrick O'Donohoe would have been a name familiar to many citizens in Boston in 1853. As English rule in Ireland grew increasingly oppressive throughout the 19th century, Irish immigration to Boston became a route out of the devastating famine and tumultuous political atmosphere. This resulted in a large demographic shift in Boston through the mid-1800s. Even after crossing the Atlantic, many Irish immigrants continued to closely follow the politics and news of their homeland, resulting in significant media attention dedicated to following Irish news.

It is because of these demographic shifts and the large Irish population that the name Patrick O'Donohoe was well-known in Boston prior to his arrival and visit with the bishop in 1853. O 'Donohoe entered the public sphere in 1848 as a member of the failed Young Irelander Rebellion that sought to stand up to the injustices imposed by the English government. Joined by William Smith O'Brien, Terence MacManus, and Thomas Francis Meagher, O'Donohoe and his nationalist peers were arrested by the English government. The rebellion and subsequent punishment of the rebels garnered international support and newspapers from Ireland, Australia, and Boston followed the tale of the Irishmen. While O'Donohoe and his peers were initially sentenced to be hanged, the punishment was altered by the crown, and the men were instead sent to penal colonies on the island of Tasmania off Australia, known at the time as Van Diemen's Land. Despite the harsh punishment, public support for the Irishmen remained unwavering. According to The Boston Pilot, as the men arrived by special train to be deported to the penal colonies, "a very large crowd had assembled outside the terminus, and as the cars passed . . . The people cheered loudly, and followed them."

Public support continued for O'Donohoe and his fellow state prisoners, as evidenced by the reporting of The Boston Pilot. For the next five years, O'Donohoe and his fellow prisoners engaged with the press, mainly through a paper known as The Irish Exile. In one letter, reprinted in The Boston Pilot in 1851, Meagher and O'Donohoe lamented the mistreatment of the prisoners in the penal colonies, referring to the government as one "of gags and gangs . . . All this miserable, plebeian (sic.), fifth-rate Government wanted was, to have the entire band of the Irish Rebels unconditionally and completely in their power." Echoing this, O'Donohoe stated that "I have two broken ribs, and cannot cough without great pain. I really never felt so ill in body and mind." However, he added that once he was deemed healthy by the government doctor "off I go -- in grey of course, and for my daily labor" in the prison chain gang.

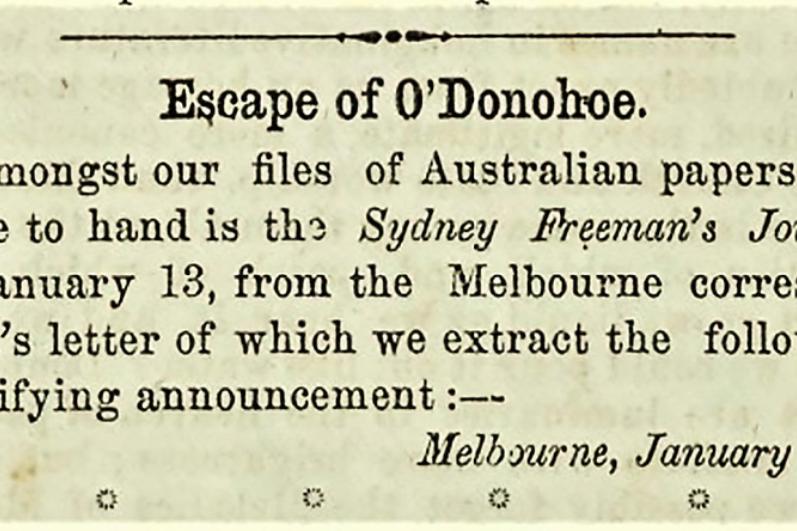

While local newspapers in Boston continued to provide updates on the "State Prisoners," as O'Donohoe, Meagher, O'Brien, and MacManus were often referred to, the narrative changed in June 1853. "Another of the Irish State Prisoners has escaped from Van Diemen's Land . . . To add another to the thousands of Irishmen whom Saxon rule and Saxon wrongs have expatriate from their dear old land," The Boston Pilot reported, breaking the news of O'Donohoe's escape to citizens of Boston.

Although reports of O'Donohoe's escape didn't appear in newspapers until June, his escape began in February. As he and his fellow rebels had done before, he published his account in local newspapers, using the journal he had kept along his journey. The rather lengthy account, published in The Boston Pilot on Aug. 6, 1853, demonstrates the intense circumstances of O'Donohoe's flight from prison. In one segment, O'Donohoe captures the physical discomfort of his escape in vivid detail. Trapped within the ship engine, O'Donohoe "was thus ensconced in a compartment about seven feet in length, three in width, and two in height; and by its formation I was obliged to lie in a recumbent posture . . . When the furnaces came to blaze in full strength, the heat and want of air made the den very insupportable. I dreaded instant death by suffocation or apoplexy." Despite the poor conditions, his ship being struck by lightning, and contracting dysentery, O'Donohoe arrived safely in San Francisco on June 22, 1853.

It is in this context that Patrick O'Donohoe, the escaped Irish rebel from 1848, called on Bishop Fitzpatrick to meet. Despite the international support that O'Donohoe had garnered through his reports to The Irish Exile and subsequent newspapers, Bishop Fitzpatrick's journal casts a rather unpleasant image of the Irishman. Noting that O'Donohoe appeared "evidently in a state of high excitement caused partly by fatigue of traveling and partly by liquor," the bishop added a rather scathing remark that "he seems to be a man of hot impulses, honest purpose, sound Catholic faith and small brains, in no respect fitted to be the counselor or leader of a people."

Just weeks later, O'Donohoe once again found himself in the local newspapers. This time, however, it was not for rebelling against oppressive governmental regimes. Instead, he was charged with intentions of fighting a duel and forced to go to trial in Boston at the end of the same month he arrived, perhaps due to the "hot impulses" noted in Bishop Fitzpatrick's journal.

JOY ZANGHI IS AN ARCHIVIST FOR THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.