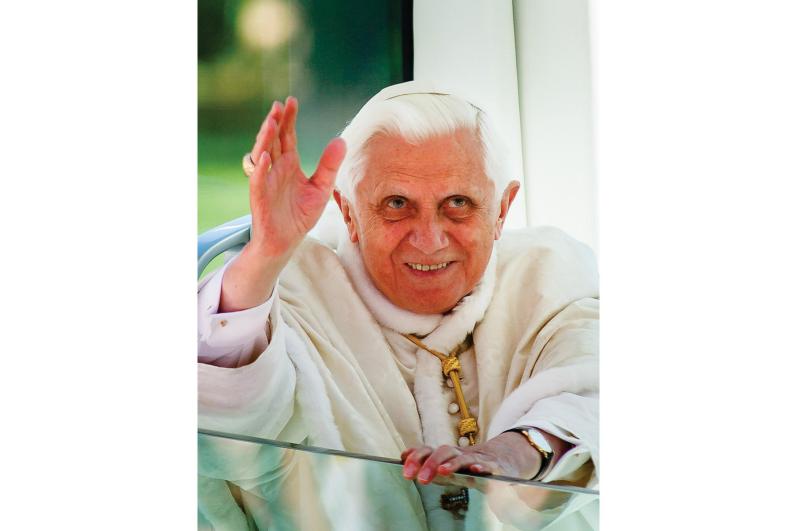

Cardinal O'Malley reflects on Pope Benedict's legacy

As he was preparing to depart for Rome to attend the funeral of Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, Cardinal Seán P. O'Malley spoke to The Pilot Jan. 2 about his experiences with the late pope and his impact on the Church. The interview has been edited for clarity.

Q. You had many personal interactions, first with Cardinal Ratzinger and then with Pope Benedict XVI. How would you describe him -- his character and demeanor?

He was certainly a very gentle and kind person. He was extremely brilliant intellectually but very respectful of other people. He didn't use his brilliance as a way of overwhelming or putting people down. He was always searching for the truth and always searching to be faithful to the traditions of the Church. But he was always kind and respectful, even to those who did not share his convictions.

Q. Some coverage of his passing describes him as a fundamentalist and as "God's Rottweiler." What is your reaction when you read such descriptions?

Well, it's a complete distortion of his personality and his character. Anyone who had the opportunity to be with Cardinal Ratzinger or Pope Benedict realizes that that is a very false characterization of him.

Q. Can you underline a particular theme of his theological writings that impressed you the most?

First of all, as someone had said years ago: Huge crowds used to go to Rome to see John Paul II, but huge crowds came to Rome to hear Benedict XVI because Benedict had a wonderful way of preaching the Gospel and explaining the doctrines of the faith with a strong pastoral dimension and in a way that helped people to understand the teachings of the Church.

Certainly, he was very anxious to promote a hermeneutic of reform and continuity in the Church. Some people try to see the (Second) Vatican Council as blowing everything up and starting all over again, but that was not what the council was about. And certainly, Pope Benedict was a very strong supporter of the council but saw it as a part of the trajectory of the history of the Church. His participation at the council and his involvement in starting the theological journal Communio with (Henri) de Lubac and (Hans Urs) von Balthasar were an indication of his theological ideas and his commitment to teaching the faith with clarity.

His writings, particularly his Christological writings, his three volumes on the life of Christ, are so moving and a real testament to his deep faith. I always tell people that I think a hundred years from now, priests, religious, and others will be reading his writings in the breviary like the great Doctors of the Church of the past. He certainly was very Christocentric in all of his theology, very much influenced by St. Bonaventure. His books and sermons will be one of the most important parts of his legacy in the Church. His theological reflections and teachings will continue to be read and help to mold people's hearts and minds in the Catholic faith.

Q. How important was his role, first as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and then as pope, in the painful path to address the issue of sexual abuse of minors by clergy?

He was the first prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith that really dealt with this issue, and, of course, the emblematic figure of all of this was the terrible case of Father (Marcial) Maciel in Mexico, whom Cardinal Ratzinger worked to remove. He introduced many changes to the CDF to begin to make them more capable of dealing with the cases coming to the discipline selection. Before, the CDF was basically dealing with theological reflections, and he saw the need to address the problem of abuse, and, as I said, it was right at the beginning of the crisis.

When he became pope, he was the first pope to meet with victims, and I was involved in taking victims and survivors from Boston to Washington, where we met with him in the nunciature. That was a very moving experience, and I think it made a tremendous impact on Benedict himself. Later on, he also met with victims of abuse in Australia, and he said that he had no words to describe the pain and harm inflicted on the survivors.

He also was the first to write a pastoral letter on the sexual abuse crisis in 2010 concerning the situation in Ireland, and he sent a number of cardinals to be visitators in different aspects of (the Church in) Ireland. I was sent on an apostolic visitation to Dublin, and Cardinal Dolan visited the seminaries in Ireland.

So, there were a number of steps that Pope Benedict took around the whole area of sexual abuse. He removed 400 priests from ministry, and I think the Holy Father's decision to resign, in part, was his realization that someone else would need to come in with more health and energy to be able to address a lot of these terrible problems that the Church was facing. In many ways, I think his decision to step down was part of his desire to see the reforms of the Church go forward in a way that he didn't think he would be able to do. So, there was a lot of humility in his own realization of the needs of the Church and his own capabilities to address those specific needs. Certainly, his theological prowess and his great intellect were such a gift to the Church, but I think Benedict understood that, at this moment in history, there were other kinds of crises that would require someone else to address.

Q. In Pope Benedict's recently released spiritual testament, he addresses the issue of faith and reason, particularly calling Catholics to hold on to the faith and not to be confused by some statements from science that seem to be at odds with the faith. Can you speak to that concern?

I think this is something that we already see in the writings of John Paul II, who, of course, had him as a very close collaborator. But certainly, in today's world, some people are making science the new religion, and this is very perilous. The Catholic point of view is that there is not a contradiction between faith and reason. There is a more fundamentalist strain of Christianity outside the Catholic Church that sees any attempt to explain Christian beliefs in light of science as a betrayal and as a lack of faith. But the Catholic position has always been that there is one truth, and so science and faith are going to lead us to the same place.

Science is always dealing with things that are measurable. Things that are measurable are improved when the instruments of measurement improve but never reach the absolute truth that faith speaks to us about. So, science allows us to discover a lot about the world around us, but it does not tell us what the value of things are, who we are, why we are here, and what our mission is.

For a man like Benedict, who saw the terrible injustices and violence of the Second World War, where so many of the marvels of technology and science were put at the service of aggression, violence, greed, and inhumanity, it becomes very clear that a scientific approach is not enough. We need to deal with the morality that comes from a faith perspective that allows us to discover the dignity of each and every human person.

Q. How consequential do you think Pope Benedict's legacy will be for future generations?

tI think his legacy will be very important because his writings continue to generate so much interest -- and they will continue to do so. He wrote about themes that are important to modern people. And he helped people to understand the teaching of the faith and the continuity of our tradition in a way that helps people to see the truth of the faith not as, as he put it in one of his writings, as a weight that drives us down but that lifts us up. I think that he will continue to be one of the great lights of Catholic theology moving forward.