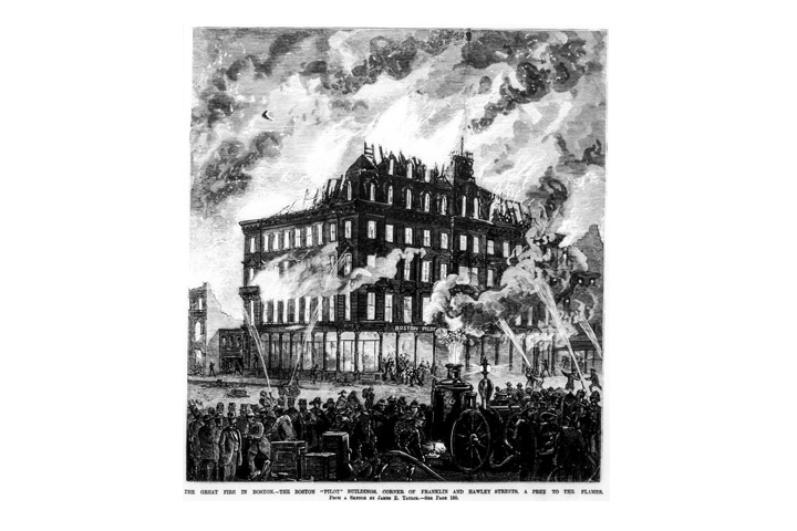

The Pilot building is destroyed in the Great Fire of 1872

This month marks 150 years since the Great Boston Fire of 1872, which killed 30 people, reduced Boston's commercial district to rubble, and caused nearly 75 million dollars of building and personal property damage. Among the buildings destroyed in the fire was the The Boston Pilot building on Franklin Street.

On the evening of Nov. 9, 1872, Patrick Donohoe, the founding editor of The Pilot was at the annual dinner of the Boston Press Club. During the evening's festivities, he was called upon to make a brief speech. He stood and reflected on his career, on how far he had come since his days as a young printer's apprentice at the Boston Transcript. During the speech, a colleague from The Pilot would later write, "Every one present saw in mental vision the magnificent evidence of his successful career, The Pilot Building on Franklin street, which was to be a pile of ruins before morning."

Around 9 p.m., a messenger arrived at the dinner and informed Donohoe that a fire had broken out and was raging on Summer and Otis Streets. The Boston Fire Department would later determine that the fire had started around 7 p.m., in the basement of a dry goods store at the corner of Kingston and Summer Streets. Donohoe proceeded to the Pilot building, alarmed but not overly worried, since his building was at the far end of Franklin Street, a fair distance from Summer and Otis Streets.

Donohoe arrived to find his building engineer in the basement, filling a tank with water. By 9:45 p.m. the engineer "had 40 pounds of steam in the gauge; and all then being ready, the rubber hose was carried to the roof by the elevator, and poured in an abundant stream over the asphaltum covering and the sides of the building nearest the approaching fire."

The Pilot's managing editor, John Boyle O'Reilly, had accompanied the engineer to the building's roof. He remained there for hours, watching the fire consume building after building, getting ever closer to the Pilot building itself. His first-hand account of the fire, later printed in The Pilot, is vivid, conveying a sense of the cold dread he felt as he waited for the fire to approach his office.

When he and the engineer arrived on the roof, O'Reilly wrote, "Franklin street was alive with yelling firemen, panting and puffing steamers . . . The gaudy steamers were like toys beside the looming masses of smoking (sic) granite which they presumed to master." As it advanced, "the amazing strength of the fire was fairly shown. The massive granite structures on the south side of Franklin Street, felt its dread presence, and smoked and cracked . . . Masses of granite sprang from their places with a report, as if shot from a cannon."

Just after midnight, the fire reached the Pilot building's mansard roof, forcing O'Reilly to abandon his post. Arriving at the first floor of the building, he found Patrick Donohoe. "How is it?" Donohoe reportedly asked him, "Any chance?"

"No, sir," O'Reilly said, "The roof has caught slightly already. We'll be driven away in an hour at most."

"God's will be done," Donohoe quietly replied.

The Pilot building fell around 4 a.m. in the morning on Nov. 10. Many buildings followed, as the fire continued to rage uncontrolled until the middle of that day. Boston's fire chief, John Damrell, and Mayor William Gaston resorted to intentionally blowing up buildings in the path of the fire in an attempt to rob the blaze of its fuel. Citizens packed buildings with gunpowder kegs, but the projectiles from the explosions caused yet more difficulties for the firefighters and resulted in civilian injury.

Every fire company in Boston was involved in fighting the fire, as well as companies from nearly every neighboring city and town. Eventually, companies from every New England state except Vermont were on scene. A company from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, is widely credited with saving the Old South Meeting House on Washington Street.

In the end, the scale of the destruction was unimaginable. Thirty people, including at least 12 firefighters, died in the fire. Sixty acres of ash and rubble were piled where more than 600 buildings once stood. Total building and property losses amounted to $75 million, the equivalent of roughly $1.5 billion today.

Yet, the rebuilding process was swift in the heavily-insured business district, and within a few years, a new commercial area sprung from the ashes. Some of Boston's great architectural treasures, including Trinity Church, were constructed in the aftermath of the Great Fire. New fire codes were adopted and the budget of the city's fire department was increased in an effort to prevent future tragedies of the scale of 1872.

But for Patrick Donohoe, the Great Fire marked the beginning of a period of misfortune that would last for the rest of his life. In 1872, Donohoe had been the richest Catholic in New England. His office and publishing house on Franklin Street was noted for its grandeur. His home on Boylston Street was one of the city's social hubs, the site of frequent parties and events.

In the Great Fire, Donohoe's losses amounted to more than $350,000, or about $8 million today. The Pilot resumed operations on Washington Street but was burned out again in May of 1873. A third office opened on Boylston Street, but this, too, was burned out. The instability in the insurance market caused by the Great Fire meant that each time an office burned, Donohoe received less assistance. At the same time, unwise investments and real estate speculation caused his bank, the Emigrant Savings Bank, to collapse, plunging Donohoe into deeper debt. Although he went on to claw his way out of debt and financial ruin, he never recovered the monetary or social standing that he once enjoyed.

VIOLET HURST IS AN ARCHIVIST FOR THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.