Of purgatory

There are Christians who regard themselves as needing to be persuaded that purgatory exists and Christians who have long since been convinced in faith that it does exist and have for many years acted on that principle. I suggest that the defense of the doctrine of purgatory today should consist mainly of the report of the second group about their happiness rather than arguments aimed to shift, if possible, the commitments of the first.

The arguments addressed to the first, what might be called the "rational defense of purgatory," require a lot of background support. Let us suppose or prove that God exists. Let us suppose or prove that human happiness can be found only in a possession of God. But only the completely good, the "perfect," which our Lord enjoined all of us to be, can endure to be in the presence of God. But hardly anyone (if experience counts for anything) is completely good upon death. (Read an account of the "heroic virtues" of some canonized saint and use that as your standard, your "canon.") And yet many who die while not completely good are in a state of grace, enjoying friendship with God. Therefore, there must be some divine provision for the cleansing -- the purgation -- of the faults, flaws, and lingering blemishes of such souls after death.

Add: there are passages in Scripture and the writings of early Christians that support the practice of praying for the dead, but our prayers are unnecessary for souls either in heaven or in hell. And saints, popes, councils, and Mary in her apparitions, have taught the reality of purgatory. Add also: What could be more natural, if we pray for one another now, to continue to pray for others after they die? And wouldn't it be a fitting "divine economy" if, after departed souls have been helped by our prayers, they should, in turn, when in safety, assist us by their prayers in gratitude?

These arguments are wholly sufficient. And yet, there are arguments, and there is life. The best reasons for an age of unbelief, for a people who typically do not search for arguments and then decide to live on the basis of the best arguments, are the "reasons of which the reason knows nothing," which are shown in the lives of believers and appeal to the heart. These require no background support and make this offer to our unbelieving friends: You can have this happiness, too, if you believe.

St. John Henry Newman was one of the best advocates of this "apologetics of the imagination and of the heart." Although a master reasoner, he scorned arguments as the mode of conversion, the approach of the time known as "evidences of Christianity." Another was Francois-Rene de Chateaubriand (1768-1848), a generation earlier than Newman, whose masterwork, "The Genius of Christianity," almost on its own turned back the anti-clerical, laicizing momentum of the French Revolution and prepared the way for Christian romanticism. Given the analogies between our own time and post-Revolutionary France, Chateaubriand deserves new attention.

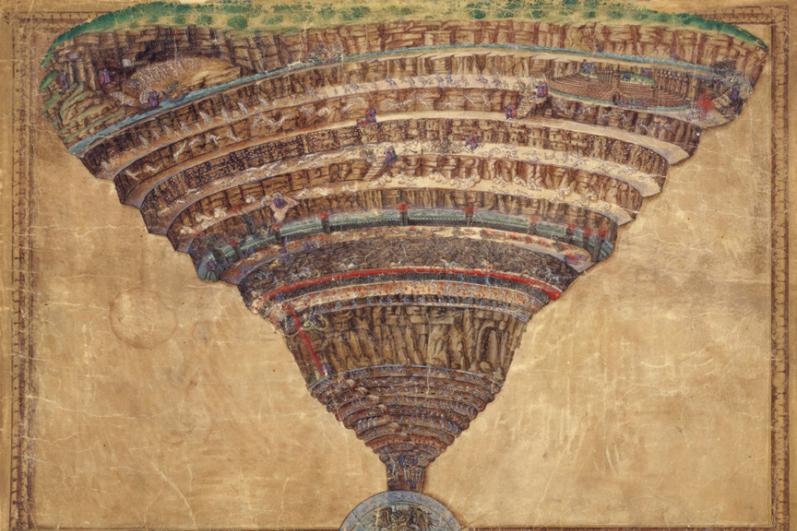

Chateaubriand's remarks on purgatory might be used as a commentary on Newman's great poem, "The Dream of Gerontius," about a man's experience when he dies and is greeted by his guardian, who leads his soul up to the throne of God, where he is judged worthy of entering purgatory. "Nothing, perhaps," Chateaubriand says, "is more favorable to the inspiration of the muse than this middle state of expiation between the region of bliss and that of pain, suggesting the idea of a confused mixture of happiness and suffering." Purgatory is more poetic by its nature than heaven or hell "because it possesses a future, which they do not."

The doctrine of reincarnation, Chateaubriand observes, has been believed for the same reason that Christians believe in purgatory. But, he says, in language later echoed by Chesterton in "Orthodoxy," "Whatever can be measured by the human mind is necessarily circumscribed. We may admit, indeed, that there was something striking and true in the circle by which the ancients symbolized eternity, but it seems to us that it fetters the imagination by confining it always within a dreaded enclosure. The straight line extended ad infinitum would perhaps be more expressive, because it would carry our thoughts into a world of undefined realities and would bring together three things, which appear to exclude each other -- hope, mobility, and eternity."

Children whose imaginations are healthy easily picture purgatory and become concerned for souls there, beginning with family members. No doubt purgatory was a more lively object of prayers when family members more often died young. Purgatory testifies to a love stronger than death. "How admirable the intercourse between the living son and the deceased father -- between the mother and the daughter -- between husband and wife -- between life and death!" Chateaubriand aptly comments, "What a beautiful feature in our religion, to impel the heart of man to virtue by the power of love, and to make him feel that the very coin which gives bread for the moment to an indigent fellow-being, entitles perhaps some rescued soul to an eternal position at the table of the Lord!"

The best reasons for believing in purgatory are found in the happiness that belief in purgatory brings to Christians. A lively belief leads to a lively happiness, which in turn can be seen by others. "I want that happiness" is how Christianity spreads.

- Michael Pakaluk, an Aristotle scholar and Ordinarius of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas, is a professor in the Busch School of Business at the Catholic University of America. He lives in Hyattsville, MD, with his wife Catherine, also a professor at the Busch School, and their eight children. His latest book is "Mary's Voice in the Gospel of John" available from Amazon.