Repairing the relationship between priests and bishops

On Oct. 19, the results of the National Survey of Catholic Priests were released by The Catholic Project and the Department of Sociology of the Catholic University of America.

The National Survey, the largest study of Catholic priests in America in more than 50 years, is an ambitious attempt to assess the state of the priesthood in the United States as the Church marks the 20th anniversary of the "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People."

Conducted by Gallup between February and June this year, the Survey sought to interview 10,000 of the 35,000 Catholic priests in the country; 3,516 priests from 191 dioceses and eparchies responded. The authors likewise engaged the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (CARA) to survey, between October 2021 and February this year, all of the Archbishops and Bishops who head the 195 US Dioceses and Eparchies, obtaining responses from 131 of them. So the results are quite significant, involving the input of over 10 percent of the priests and 67 percent of bishops in the country.

The National Survey was interested specifically in assessing how the abuse crisis, and the Church's institutional response to it, have affected priests' overall well-being and impacted their relationship with their bishops.

The responses showed that despite 77 percent of priests being characterized as "flourishing" according to the categories of the novel (2017) Harvard Flourishing Measure, there are some major concerns. 45 percent of priests report at least one symptom of ministry burnout, and nine percent show severe burnout, characterized by chronic emotional and physical exhaustion and high levels of stress. The burnout is particularly acute among young priests.

The biggest concerns, however, involve the toll the response to the clergy sexual abuse crisis has been having on priests' sense of vulnerability and their trust in their bishops.

When the U.S. Bishops convened in Dallas in 2002 to draft the Charter and its accompanying Norms, they did so hurriedly and under enormous pressure from the press, lawsuits, and furious faithful. They got most of the big stuff right in terms of holding offenders accountable, responding quickly to allegations, cooperating with civil authorities, committing to the healing and reconciliation of victims, and ensuring that the priesthood -- and parish staffs and volunteer teams -- were no place for those who would harm the young.

The priests in the National Survey overall were highly supportive and appreciative of these efforts, with 90 percent of priests saying that their dioceses have a strong culture of child safety and protection and nearly two-thirds saying that the zero-tolerance policy for abuse of minors has demonstrated the Church's commitment to the young and helped regain trust.

But the priests surveyed gave stark testimony to the harms that have come from what the bishops in Dallas left out of balance.

The most noteworthy damage is that priests now feel extraordinarily vulnerable to false accusations. 82 percent of priests stated that they regularly fear being falsely accused of sexual abuse. Compounding their fear is the concern of many that if they are falsely accused, they would be treated as guilty until proven innocent and left without support. 64 percent of diocesan priests think that they would not be provided with sufficient resources by their diocese and 49 percent think they would not be supported by their bishop.

This is doubtless an effect of the fact that the original understanding of the undefined term "credible accusation" in the Charter and Norms was left undefined and was interpreted by most diocesan protocols according to an absurdly low threshold: "credible" meant only that the charge was not patently "impossible," that the priest wasn't already dead when the abuse took place and that the allegation involved a who, what, when, and where. It didn't matter if the priest had a rock-solid alibi and sterling character with youth, if the accuser had a reputation for chronic mendacity, or if the details were incoherent and contradictory.

In most dioceses still today, when a priest is accused, he loses his home, his job, his good name all within hours. He is removed immediately from his rectory and parish assignment, prevented from public ministry for the length of what is often an inexcusably glacial investigation, and required to dress like a layman. A press release is published in which the priest's reputation is injured if not ruined. He has to exhaust his meager savings or beg and borrow money to hire a lawyer. Most excruciatingly, he has to linger for months or years under suspicion of being a sadistic pervert as well as a hypocrite to the faith for which he has given his life.

Some dioceses have sought to remedy various aspects of the obvious injustices involved, like changing the criterion from "credible" to "substantiated," but even the latter can be insufficient, meaning that there's "some" evidence seeming to support the accusation. The definitions and their applications remain arbitrary, the evaluation processes hidden, and for those reasons the decisions, regardless of their outcome, remain shrouded in questions.

While 61 percent of priests believe that the civil legal process would prove their innocence -- because civil criminal procedures are known, and the presumption of innocence acknowledged -- they clearly do not have a similar confidence in ecclesiastical review boards and decision-making. They fear that things other than justice and due process would be involved in the outcome, like the diocese's reputation for zero tolerance, and all of the concerns (including financial) that flow from the diocese's having such a reputation. This would be true especially in situations in which a clear sense of what did or did not happen cannot be definitively established.

The second associated lacuna in Dallas was the bishops' failure to hold themselves accountable to the Charter and Norms. During their deliberations, they decided to change the word "cleric," which would have included bishops, to "priests and deacons," in order to exempt themselves from what they were mandating for others, a clear violation of the Golden Rule. Pope Francis' 2019 apostolic letter "Vos Estis" addressed some of the disparities, but not all.

Investigations of bishops accused of the sexual abuse of minors do not normally involve the draconian measures experienced by priests. Most (rightly) remain in office as the accusations are investigated, even if they voluntarily curtail their functions. They maintain their residences. They continue to dress as clergy. Press releases and all other aspects of the process insist on the presumption of innocence. The investigations are relatively expeditious. If their innocence is established, the press, helped by the Diocesan communications department, normally gets the news out broadly.

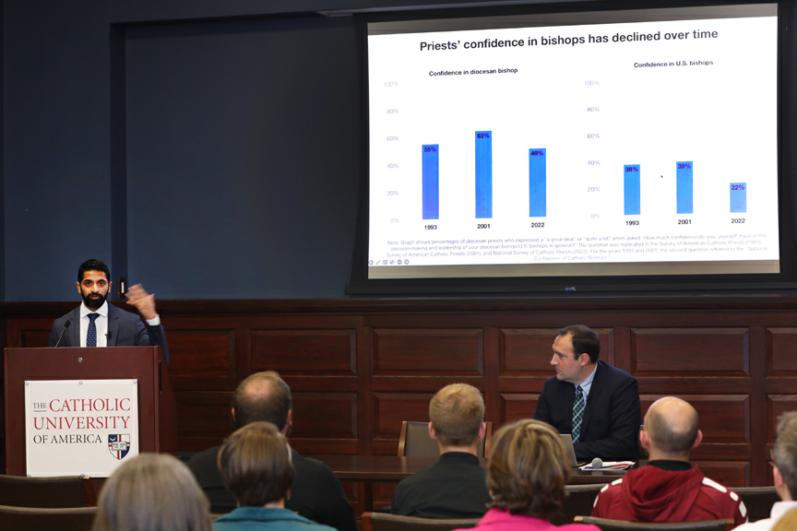

The double-standard of treatment between bishops and priests has profoundly impacted their relationship. 51 percent of priests say that they don't have confidence in their own diocesan bishop and 76 percent don't have confidence in the U.S. Bishops in general. There are doubtless several factors involved in those numbers, but it is logical that priests who do not believe that their bishops would support them and treat them justly if they were falsely accused of sexually abusing children would not have high confidence in their bishops.

The disconnect between bishops and their priests was highlighted in the Survey by the massive disparity in the way priests regard their bishops and bishops think they're regarded. Whereas 73 percent of bishops view priests as their brothers, only 28 percent of priests say that the bishops treat them that way. Similar discrepancies happen relative to bishops' behaving as spiritual fathers (70 to 28), co-workers (73 to 32), and servants (68 to 34). Priests mainly regard their bishops as administrators or CEOs who treat them as employees (55 percent), while only 44 percent of bishops identify as such.

The biggest disconnect, however, between the way bishops view themselves versus the way their priests regard them is over whether bishops could be counted on to help one of their priests who was struggling. 90 percent of bishops said that they would be there for such a priest, but only 36 percent of priests thought their bishop would.

There are, of course, many bishops who have high marks from their priests for their fairness, closeness and other virtues. But it is nothing short of shocking that 30 percent of bishops don't look at themselves as spiritual fathers to their priests, or 27 percent as their brothers, or 27 percent as their co-workers. It's more staggering that ten percent of bishops admit they would not be there for priests who were struggling.

It's time, however, for the 90 percent who say they would be there for their priests to digest this survey and recognize that the vast majority of their spiritual sons, brothers and co-workers are indeed struggling and need their help. And the particular help they need is a prudent and just revision of the obvious deficiencies in the Dallas Charter and Norms, so that they no longer have to live under the threat of the cataclysmic consequences of a false accusation.

That way they can begin to live anew in right relationship to the bishops to whom they have promised respect and obedience until death and whom the Church theologically wants them to regard as faithful spiritual fathers, brothers, collaborators and shepherds.

- Father Landry is a priest of the Diocese of Fall River who is national chaplain to Aid to the Church in Need USA, a Papal Missionary of Mercy and a Missionary of the Eucharist for the US Bishops.