A portrait in ordinary time

Years ago, I was in an art gallery in Amsterdam.

In contrast to the sacred themes abundant in the southern European art with which I am more familiar, the masterpieces of Dutch art have more secular themes. Centuries ago, authorities in the Netherlands disfavored public displays of religious art. Hence, Dutch collections of fine art feature beautiful still life paintings, landscapes, and portraits instead.

The portraits captured my imagination -- as portraits often do. Many were of individuals dressed in their finest and depicted with their homes and possessions in ways that invited me to speculate as to who they were and how their long-ago lives were led.

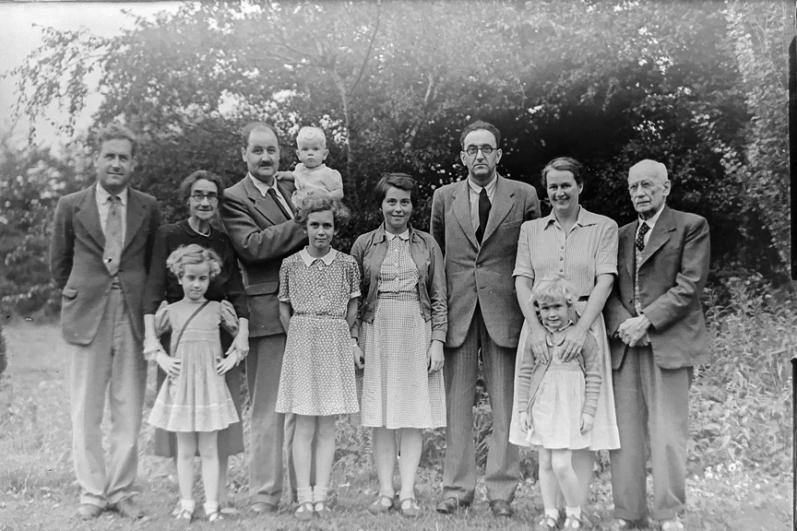

Many portraits were not of solitary individuals. They were family portraits of children posing with beloved pets and toys alongside adults dressed in ways that announced their station and status. These portraits celebrated the family ties that bound them together.

However, along with the men, women, and children in the family portraits, there were additional figures in many paintings that I did not recognize. They were small, often dressed in white, and sometimes wearing the clothes of an adult while having the faces of children. They were not exactly angels, yet they looked different from the others in the portrait. I was intrigued.

There was a docent in the gallery whose face conveyed the unmistakable boredom of a long day when no one was asking questions, and none of us docile art lovers were touching the paintings or taking the flash photos that would have demanded her attention. So, I inquired about these diminutive figures.

She told me that they were placed in the portraits to represent children in the family who died in the womb and were delivered, stillborn, into the world or children who died in infancy. Both of these were tragically common occurrences. She memorably explained that only by including those whose journeys through life were so fleeting could the family portrait, in her words, be "complete." Those not blessed with the years to walk through life with their families were remembered by this artistic convention because, truly, the family portrait was not "complete" without them.

October's "Respect Life" month is an opportunity to examine the portrait of our own human family. It is a vibrant portrait, full of people from all walks of life, of all ages, races and nationalities, with the strengths, limitations, gifts and flaws that make our portrait rich with individuals unique and irreplaceable.

Yet . . . So many are missing.

Since 1973, in the United States alone, well over 60 million irreplaceable people have been taken from our portrait before they were delivered into the world. Similar tragedy unfolds around the globe every hour of every day. Those missing from our family portrait are not merely the infants whose lives ended so early -- but the children, young adults, middle aged people, and elders they would have grown up to be. Missing, too, are the families they would have founded, the children and grandchildren they may have had, the irreplaceable contributions they would have made, and the joys -- and sorrows, too -- that they would have brought to the portrait of our human family.

Also missing from the family portrait are, all too often, the very eldest among us who are cast out of the portrait when they are at their most vulnerable. In a literal sense, there are family pictures taken every day that do not have older generations in them because those gripped by weakness, illness, and dementias are no longer invited to join the young, healthy, and strong around the family table. At the extreme, a steady drumbeat in favor of legislation that would allow ending the lives of the ill would steal still more from the family portrait.

In between life's very beginning and very end, many others are also cast from the family portrait because they are victims of a throwaway culture that discards so many who bear the scars of hard lives in a world that can be cruel.

Yet, it need not be this way.

Respect Life Month is an opportunity to acknowledge what those artists from yesteryear knew: our family portrait is incomplete if it does not include all.

It is an opportunity to mourn, humbly and honestly, for all those who are missing from the family portrait. It is a chance to ask ourselves, in the quiet of our own hearts, whether we played a role in making this so by what we have done and failed to do. It is a month to resolve to end anything that keeps others out of our family portrait, especially during the sacred vulnerability at life's very beginning and very end.

Like those artists of so long ago, it is a time to recommit to doing all we can to make our family portrait "complete." We are far poorer as a human family because of all those who are missing. In their honor and in their memory we can make a fuller, holier family portrait in this special, sobering month of ordinary time so people can be creative in beautiful ways. They make the art, music, literature, and drama that inspire the world. Others are creative in more practical ways. They build buildings, invent machines, find cures, and solve.