Judge Martin T. Manton's bid for a Supreme Court seat

On Sept. 12, 1922, Bishop Thomas E. Molloy of Brooklyn wrote a letter to Boston's Cardinal William H. O'Connell. "Your Eminence," he began, "A distinguished Justice of the U.S. Circuit Court and a practical Catholic of this diocese, the Honorable Martin T. Manton, is mentioned very favorably for the U.S. Supreme Court, on the occasion of the next vacancy."

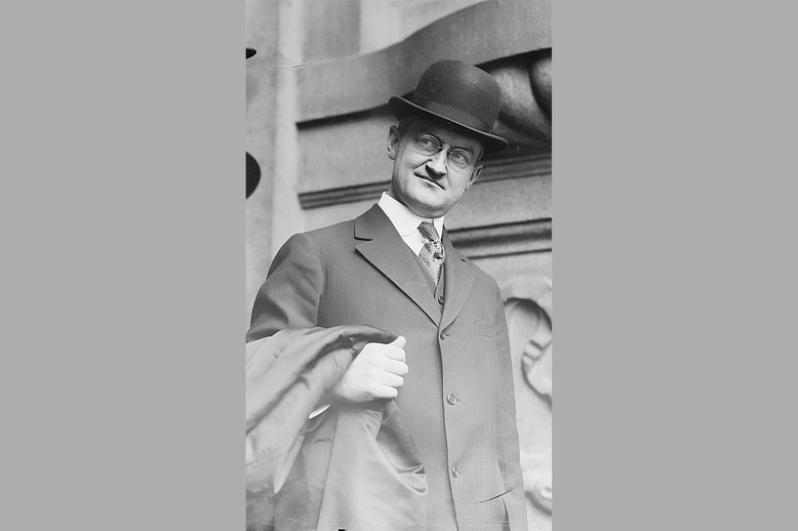

Judge Martin T. Manton was born on Aug. 2, 1880, in New York City. An Irish Catholic of humble origins, he was a standout student at Columbia Law School, where he founded the university's law review. After earning his bachelor of laws, he entered private practice, first joining the law firm of William Bourke Cockran, an influential Irish-American politician and orator who was an early mentor of Winston Churchill. As a lawyer, Manton was immensely successful, earning more than $1 million in 15 years -- an enormous sum for the time. He was also well-connected, befriending political and business leaders throughout the five boroughs.

On Aug. 15, 1916, Manton was nominated by President Woodrow Wilson to a seat on the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. He was confirmed by the Senate on Aug. 23, 1916, and served on the court for two years before his elevation to the Second Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, widely considered to be the second-most influential court in the nation -- second only to the Supreme Court. It was on this court that he served in 1922, when rumors began circulating that Justice William R. Day was preparing to retire from the Supreme Court.

At the time of Justice Day's retirement, it was tradition that presidents would make bipartisan appointments to the Supreme Court; that is, they would alternate appointing Democratic and Republican justices. Since President Warren G. Harding had most recently appointed a Republican (former Utah Senator George Sutherland), Justice Day's seat was to go to a Democrat; and, in keeping with the Supreme Court tradition of always having a "Catholic seat," it was to go to a Roman Catholic. Justice Manton fit the bill, and his name quickly rose to the top of the president's "short list" of nominees.

Manton sprang into action, lobbying his friends and allies to support his appointment. Knowing that he would need to curry favor with the Senate Majority Leader, Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, he sought to reach out to him through the Catholic hierarchy. He approached the Bishop of Brooklyn, who in turn penned a letter to Cardinal O'Connell in Boston.

"Justice Manton has informed me that Senator Lodge would probably consult Your Eminence in reference to available Catholic candidates for this high office," the bishop wrote. "He wishes, therefore, to make known his identity to Your Eminence in case any inquiry should be made in reference to him."

The bishop went on to say, "I should be reluctant, indeed, to trouble Your Eminence with this were I not impressed by the consideration that Catholic interests might be advanced in having practical Catholics in important positions of State."

With a nod to propriety, he hastened to add, "I assured Justice Manton that Your Eminence would refuse absolutely to become involved in this matter if your actions would be interpreted as political in any way," and that it could of course be the case that "Boston may have Catholic talent to be devoted to the U.S. Supreme Court."

Still, the bishop wrote, "Justice Manton will be satisfied ... if I only make known his identity to Your Eminence so that you may know who he is if any inquiry were be made regarding him as he seems to think there will be."

Cardinal O'Connell's reply to this initial inquiry is not held by the Archdiocese of Boston Archives, but a follow-up letter from Bishop Molloy on Sept. 16 thanks him for the "kind and gracious disposition so generously manifested in regard to my request on behalf of Justice Manton."

As Justice Manton worked to gain Senator Lodge's support, a powerful voice began to work against his nomination. William Howard Taft, the chief justice of the Supreme Court and a former president, had made inquiries into Justice Manton's associations in New York. He consulted with members of the New York bar, including his own brother, Henry Waters Taft, and came to believe that Justice Manton was corrupt, a Tammany Hall appointee. Behind the scenes, he began to lobby President Harding to instead nominate the jurist Pierce Butler, another Catholic Democrat, to the court.

Bishop Molloy made one more appeal to Cardinal O'Connell on Justice Manton's behalf in a letter dated Oct.13, 1922. In this letter, Manton's appeals are more desperate. The bishop wrote, "Mr. Will Hays, former Postmaster General, is urging Justice Manton to request Your Eminence to drop just a word to Senator Lodge about the matter of his appointment." The bishop was somewhat embarrassed and reluctant to pass on the request, "realizing, as I do, that a Senator should first approach a Cardinal."

Cardinal O'Connell's reply came 10 days later, when he wrote, tactfully, "I assure you that I have already said in the right place a good word for the gentleman concerning whom you write." Unfortunately for Manton, a good word in the right place was not enough to secure his nomination. Pierce Butler was appointed to the Supreme Court, after securing support of his own from at least eight bishops, many of whom appealed directly to President Harding.

If the name Martin Manton sounds familiar, it is likely not because of his failed bid for a Supreme Court nomination in 1922, but it is because he was later embroiled in one of the largest scandals in the history of the Federal Court system. After suffering massive financial losses in the Great Depression, Manton began accepting loans and bribes in exchange for his votes in federal cases. In a highly publicized series of court cases, he was tried and indicted in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, where he once sat as a judge.

His appeal case brought the highest-ranking judge in the second-highest court in the country before his own colleagues. Given the number of judges who had to recuse themselves from the trial due to their personal acquaintance with Manton, a special federal court had to be set up to hear the appeal. Some of the leading political figures in the nation, including former Democratic Presidential candidates Alfred Smith and John W. Davis, were called as character witnesses at the trial.

In the end, Manton was sentenced to two years in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary and served 17 months.

VIOLET HURST IS AN ARCHIVIST FOR THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.