The archdiocese in eight maps -- 1870 and 1872

This is the third in a series of four articles about the changing geography, or better, the borders of the Archdiocese of Boston. These also focus on the Diocese of Providence, which concludes its sesquicentennial observance on June 26, 2022.

For the next 17 years, the borders of the New England dioceses remained the same. In 1870, another change was made, again at the suggestion of the bishops of the New York province, that a new diocese be made in Massachusetts. Boston's Bishop John J. Williams initiated the proposal as he saw the happy expansion of the Catholic faith and its more evident expression in new parishes, schools, and other institutions.

Bishop Fenwick's College of the Holy Cross in Worcester was joined by its new cousin, Boston College, established in 1863 within walking distance of the site chosen for the new Cathedral of the Holy Cross in Boston's South End.

In spite of the national turmoil of the Civil War, the shock of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the initial steps of Reconstruction, the Church was still growing in population and physical presence. This was especially evident in the nation's "northeast quadrant" -- the territory encompassed by the U.S. border with Canada to the north, following it west from the Atlantic Ocean to a bit beyond the Mississippi River, then south to about what would be the Mason-Dixon Line or the 36th parallel, then east back to the Atlantic.

The history of the Catholic Church in the U.S. in the nation's first century was largely that of the Church in that "quadrant" -- with the caution that the Church had been long planted in Florida, Georgia, Texas, areas now Arizona and New Mexico and along the Camino Real in California with its trail of Missions.

While there is the temptation to review history through biographies of bishops or histories of institutions -- both of which are important -- the fact remains that then, as now, the Church is really seen and experienced by both Catholics and their fellow non-Catholic Americans on the very local level of the parish -- its people, clergy, its school, and women religious.

As people poured into the U.S. from across the globe, many escaping political upheaval, wars or rumors of war, religious persecution, and economic disaster, the population of newcomers swelled. As they began families of their own here, they wanted the Church to be part of their lives. Catholics begged bishops to establish parishes and to open schools to meet their needs for the sacramental life and assistance in handing on the faith to their children.

With seemingly no end in sight to this growth, bishops struggled to meet the requests of new peoples and new families. The sheer size of a diocese made it impossible for the bishop to know his people in any real sense. So this fell primarily to his priests, who were always in short supply in relation to the just demands of the people.

Even as means of transportation developed, better roads and then railroads, bishops found it increasingly difficult to visit their dioceses. Records of national and regional meetings of bishops, usually having priests along as advisors, show that this was a top concern in these years. Recommendations from the meetings flowed regularly to the Holy See, and the plea for the creation of new dioceses was usually met with approval. Though trans-Atlantic communications played a role in delays, by and large, the proposals were accepted as sent from the United States. There was a sense at the Holy See that those who were in place probably knew what would work and would not.

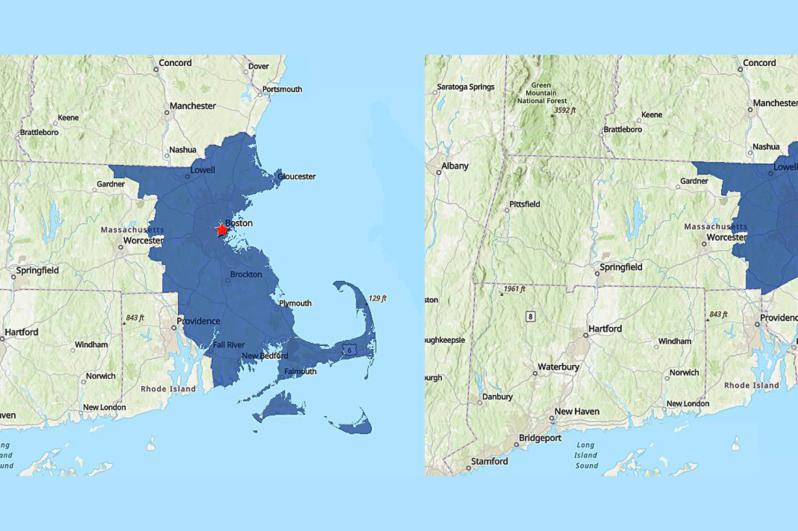

The next change for the Boston Diocese came in 1870 when the diocese of Springfield was created by Blessed Pius IX. The four western counties of the Commonwealth: Berkshire, Franklin, Hampden, and Hampshire, and the central and largest in territory of the counties, Worcester, were separated from the Boston Diocese and the new see city established at Springfield with the parish church of St. Michael there to be the cathedral church.

The new diocese had larger cities at Springfield, Holyoke, and Worcester, and there were small towns hosting long-established colleges, including Amherst, Williamstown, and Northampton. The migration of new arrivals west from Boston and substantial immigration from Quebec brought growth to the area, especially to the mill towns along the Connecticut River. The Federal Armory at Springfield was a major employer throughout the Civil War and beyond.

Just two years later, in 1872, again at the suggestion of the provincial bishops, another new see was recommended and created. The new see would be designated Providence. The territory of Rhode Island was separated from Hartford. Bishop Williams, wanting to ensure the success of the new diocese, also suggested that the southeastern part of his diocese be attached to the new see.

This would be the last border change for the Boston Diocese. The four southeastern counties of the Commonwealth -- Barnstable, Bristol, Dukes, and Nantucket -- would be the new bishop of Providence's responsibility. The now dubbed "corridor to the Cape," consisting of the Plymouth County towns of Mattapoisett, Marion, and Wareham, were ceded, creating a land bridge between Bristol County and the isthmus of Barnstable County. The two island counties of Dukes and Nantucket were then reached only by boat. The new diocese preceded the construction of the Cape Cod Canal by almost 50 years.

One of the oldest parishes in New England, Corpus Christi in Barnstable, was in the region's newest diocese. The see stretched from the Connecticut border on the west across Rhode Island into southeastern Massachusetts, ending at the tip of Cape Cod in Provincetown. The cities of Attleboro, Fall River, and New Bedford would play a key role in the expansion of the Church in the Massachusetts section of the Providence Diocese.

The new diocese would be entrusted to an energetic young, immigrant, Irish priest, Father Thomas Francis Hendricken. The young bishop was ordained at the cathedral in Providence on April 28, 1872, by New York's Archbishop (and late first American named to the College of Cardinals) John McCloskey. Assisting him were Boston's Bishop John J. Williams and Portland's Bishop David W. Bacon.