The Virgin Mary is never alone

I once heard Mexican-American theologian Father Gary Riebe-Estrella, a priest of the Society of the Divine Word, tell a story that has stayed with me for many years. Let me paraphrase.

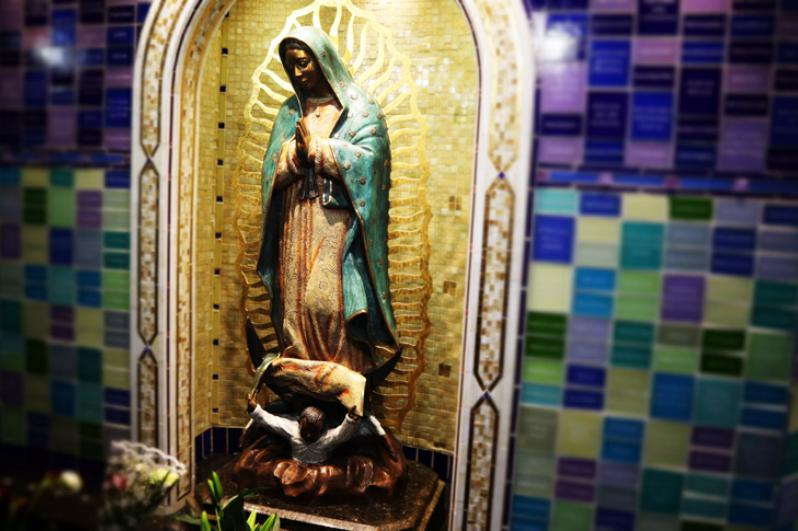

As part of his missionary work, he visited the home of a Hispanic immigrant family. As he was welcomed into the home, he noticed a beautiful small altar -- "altarcito," in Spanish -- in the living room.

Altarcitos are common in Hispanic Catholic homes. They are sacred spaces where family members place religious objects and images, pictures of relatives, relics and other things that invite to prayer. Small altars are reminders that any corner can be a space of encounter with God.

The priest's attention focused on three images of the Virgin Mary representing different Marian advocations popular among Hispanics, including Our Lady of Guadalupe. He found it interesting that they were placed next to each other.

As he struck conversation with the members of the family, and using the moment for a good catechesis, he said, "You know that there is only one Mary, the mother of Jesus, correct?"

The family, paying close attention, nodded in assent. He proceeded, "You know also that these three images evoke the same Mary, correct?" While some nodded, the mother said, "Yes, they represent the same Mary, but they are different."

Hearing this, waiting for some elaboration and perhaps anticipating the history of each advocation, Father Riebe-Estrella asked, "In what ways are they different?" The mother replied, "They are cousins."

I don't recall what happened after this interchange. I am pretty sure that a few smiles were shared, and more catechesis took place. The point, however, is that in this brief conversation, we learn a lot about how many Hispanic Catholics imagine the Virgin Mary through the experience of popular religion.

In the Hispanic Catholic imagination, closely aligned with the biblical worldview, Mary is never alone. She is always in relationship with someone.

With Jesus, her son; with Joseph, her husband; with Elizabeth, her cousin; with her neighbors and fellow country-people; with the women who suffered when their children were tortured and killed by the empire; with the apostles and early Christians who had the responsibility of spreading the Gospel.

Nearly in every narrative associated with a Marian advocation from Latin America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, after Mary appears or is found (e.g., an image, a painting) she enters in personal relationships with individuals and entire communities.

For Hispanic Catholics who express our devotion to Mary through popular Catholicism, Mary is not a distant being or a person far removed from our daily experience or our immediate relationships.

Sometimes Catholics tend to strictly define the sacred as "separated from" or "separated for." There is some truth to this, yet this does not have to mean that the sacred is equivalent to being alone or unreachable. Maybe this is why sometimes we have so much trouble relating to God and to people who serve in the name of God.

The Mary of the Hispanic Catholic imagination is holy, sacred and chosen for divine things as a member of a community. Her holiness is expressed in her relationships.

Those relationships imagined by Hispanic Catholics, as in the case of the story above, may defy the linear logic we use to interpret our religious experience. Can Mary be a cousin, a sister, a companion to herself through different advocations?

Don't jump into the rabbit hole trying to answer the question. Just dwell in the mysterious dimensions of the conviction that there is one Mary, she is never alone, and she lives in permanent relationship with us in Jesus Christ.

- Hosffman Ospino is assistant professor of theology and religious education at Boston College's School of Theology and Ministry.