The St. Patrick's Day 'panic' of 1732

As St. Patrick's Day approaches, and with it, the annual parades, concerts, and festivities, we recall a time in Massachusetts when even the slightest rumor of the celebration of the Catholic holiday stirred officials into a panic and whipped the public into an anti-Catholic frenzy.

Late in the winter of 1731, a rumor began to circulate around Boston that the city's small population of Irish Catholics would attempt to smuggle in a priest for Mass on March 17 -- St. Patrick's Day. Under Massachusetts law, Catholic priests were forbidden not only from saying Mass publicly, but also from residing in or even entering the colony. Any priest who broke this law would be sentenced to life in prison; if he later escaped from prison and was captured, he could be put to death.

The severity of the law barring priests reflected the prevailing view of ruling Puritans that Catholics were dangerous and subversive, not fellow Christians but rather idolatrous followers of the anti-Christ. In times of danger or uncertainty, Puritans reliably cast suspicion on Catholics as the "Other," convenient scapegoats on which to place blame. Indeed, the last person to be hanged for witchcraft in Boston, Ann Glover, was an Irish Catholic likely targeted for her private religious devotional practices.

So dangerous did Puritans believe Catholics to be that when, in 1691, the Second Massachusetts Charter extended freedom of religion to all Christians, Catholics were explicitly excluded. "Forever hereafter there shall be liberty of conscience allowed in the worship of God to all Christians," the Charter decreed, "except [to] Papists, inhabiting, or which shall inhabit or be resident within, such Province or Territory."

Puritans retained this harsh view toward Catholics four decades later, when speculation about an impending St. Patrick's Day Mass was brought to the attention of colonial authorities. An informant came forward, listing the names of Boston Catholics who were personally known to him and adding, "There are many Seurvants, Porters, Carters andc whose names at present don't occur. All these are pretended Chh. [Church] Men." The informant warned, "Im credibly inform'd yt they-re to have Mass said on Friday next (being what they call St. Patrick's Day)." He implored the government "to set a private guard . . . And Endeavor to apprehend ye whole body of 'em all."

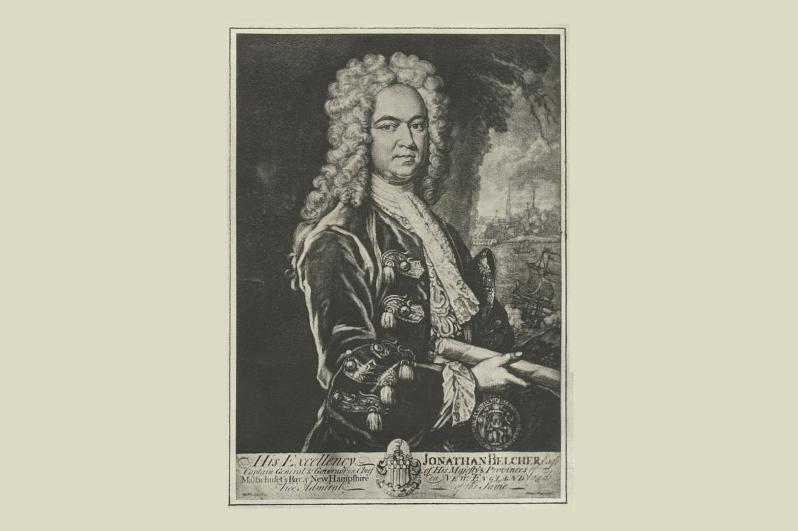

Authorities sprang into action to try to thwart the Catholics. On March 17, Massachusetts Bay Gov. Jonathan Belcher issued warrants to the sheriff, deputy sheriff, and constables of Suffolk County. "Whereas it hath been represented unto me That there are a considerable number of Papists now residing within the Town of Boston or elsewhere in sd County," he wrote, "who have Joyned with their Priest, or do speedily design to assemble together, in order to say their Popish prayers or Celebrate Masses and to use other Romish Ceremonies and Rites of Worship . . . These [warrants] are therefore to will and require you and each of you respectively in His Majesty's Name forthwith to make diligent Enquiry after and search for the said Popish Priest and other Papists of his Faith and Perswasion."

The governor exhorted law enforcement to hunt the Catholics down, writing, "You are Directed and Impowered to break open any Dwelling houses, shops, or other Places or apartments, where you shall suspect they or any of them are kept concealed." The apprehended were to be brought "before lawful Authority in order to their being secured and proceeded against as to Law and Justice appertains."

It is not known whether any Catholics were actually arrested in this incident, although one suspects not, given the lack of contemporary documentation. Nor is it known who the priest at the center of the St. Patrick's Day panic was, although in the "History of the Archdiocese of Boston," John Sexton speculates that it was Father Joseph Greaton, SJ, a Philadelphia-based missionary priest who was known to have connections to the Catholic community in Boston.

As to whether the feared St. Patrick's Day Mass took place, or was ever planned, this, too remains unknown. The only evidence for the 1731 observance of the holiday anywhere in the Colonies is found in Benjamin Franklin's Maryland Gazette, in a poem entitled "Verses on St. Patrick's Day." While decidedly deist in tone, the poem contained a verse that Catholics living in the shadows in Massachusetts likely would have hoped for their persecutors to take to heart: "As one great City was the Earth design'd / As Fellow-Citizens are all Mankind . . . / Of Whatsoever NATION they may be. Nay, tho' they in RELIGION disagree."

VIOLET HURST IS AN ARCHIVIST FOR THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.