Speak the sacred

Having seen many performances of Shakespeare's play, I have heard many actors' interpretations of Hamlet's response to the seemingly innocent question: "What do you read, my lord?"

With dry irony, or with bitterness, weariness, humor or biting sarcasm, Hamlet replies: "Words, words, words." Like his author, Hamlet had reason to be fed up with words and reason to be entranced with them. So have we all.

A dizzying variety of words is spit out at us regularly. How do we sort them out? Consider the difficulty of understanding the thought of one person you love and respect. What would it take to absorb and understand even a tiny fraction of all the thought that is thrown at us?

Words are not cheap, though we might treat them that way. Think of a word someone spoke that hurt you deeply and took you days or years to get over. Or a word that raised you up and changed the course of your life.

True words can reveal something, just as false words can deny something. When words are misused and truth relative, it produces in us an understandable anger that gets recycled as general anguish.

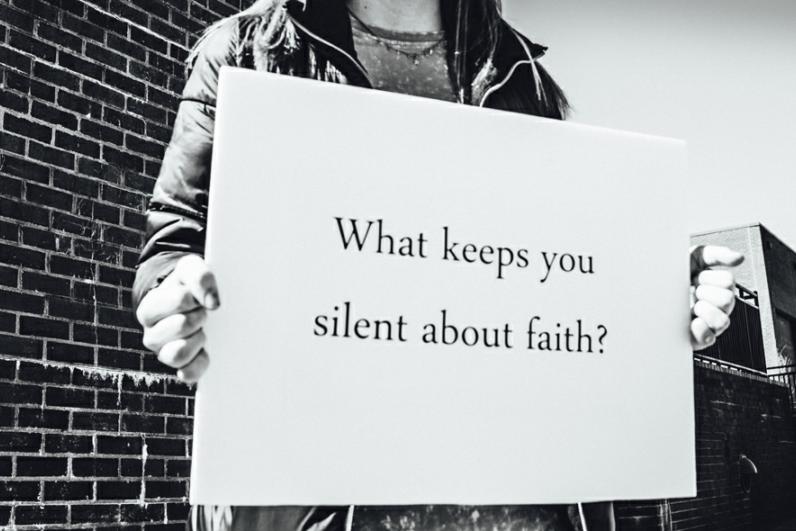

As every parent knows, part of learning language is learning to speak. Even those for whom physical speech is not possible need to learn to "speak" what is within. There is an ache inside that requires it, as Helen Keller's experience poignantly witnesses. Part of sorting out the value of others' words is learning to speak our own word.

And if the life of faith is essential to us, we need to learn to speak our faith. We all share the work of theology, the God-word: "theos" (God), "logos" (word). Theological reflection and formulation is not an elite discipline reserved for a few, to be admired or ignored by the rest. The effort to put our faith into words, for and with each other -- as we are able -- is as crucial as learning to forage and prepare food.

Truth is not easy. It is difficult, painful, "costing not less than everything," as for Christ the truth who gave everything. Dionysius the Areopagite spoke of theology's work as "suffering divine things."

This work involves a letting go, a deep learning that literally costs blood at times, a true listening far beyond words. Theological reflection is agonizing and achingly beautiful. We never say the last word -- but each word in the tradition brings us closer to what will never be defined even in eternity.

It is humiliating, and therefore teaches humility that also brings us closer to truth. It is striving toward a work never finished, since our words never can encompass the truth of divinity or even humanity; but in reaching beyond ourselves, does not our reach grow?

Theological reflection is for each of us, and for all, both personal and ecclesial.

Our faith, after all, is evidence-based. The evidence is not necessarily collected using the scientific method, but collected and sifted it is and has been for thousands of years, by people who put faith into action and words.

Evidence-based, because it is a historical faith, rooted in historical events that shaped the lives of women and men throughout history and in turn adds the evidence of their lives lived by this standard.

Seeking truth is not a passion our generation shares, yet is at the heart of the Gospel. Jesus urges his followers to do "the truth" (Jn 3:21). Christians need to be taught, so that with the whole Church we can do our work of theological reflection.

We don't start from ourselves. We start with the word of God spoken in us all, spoken on the cross and in the Eucharist, received and spoken in the Church, the body of Christ.

Our ancestors have given blood to speak the sacred, that we too might learn to speak. We might be afraid to try or unsure how. The hard work of giving faith words requires discipline.

Our October liturgical calendar presents us with an array of fellow Christians who risked to do theological reflection from their different places in the Church. We begin October with Therese of Lisieux, who never studied theology and did not live through her 25th year but is named a doctor (learned teacher) of the Church.

We continue with Luke the evangelist, who helped structure the Scriptures that also give us the word we need to live and speak, and Ignatius of Antioch, who as bishop was ordained to the role of teaching and whose theological reflection was rooted in his action and the gift of his life even to martyrdom.

But we end the month on the eve of All Saints' Day -- everyone, known and unknown to us, who has spoken their God-given word for and with the Church.

Let us help each other respond as the bride to her beloved's call, in the Song of Songs: "Let me hear your voice, for your voice is sweet."

MARY MARROCCO IS A COLUMNIST WITH THE CATHOLIC NEWS SERVICE.