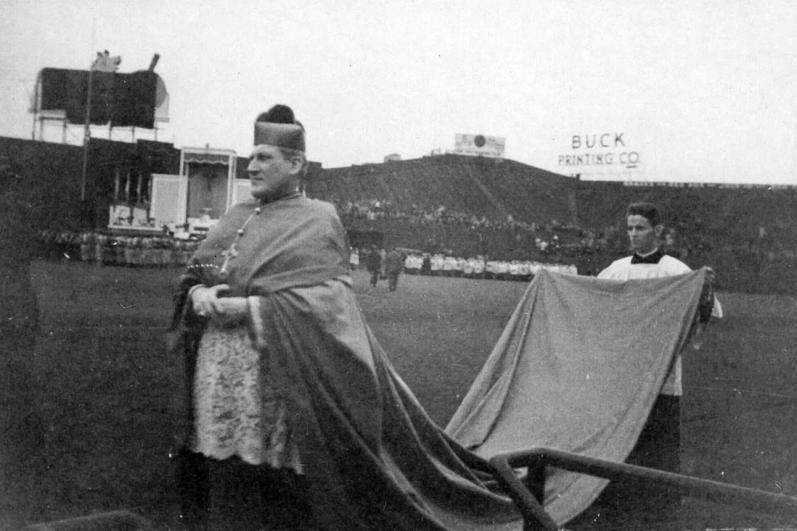

Cardinal Cushing addresses the call to holiness

On Sept. 27, 1953, the Union of Holy Name Societies hosted a meeting at Fenway Park to mark the start of a "Crusade for Sanctity" among Catholic laymen. An estimated 45,000 Holy Name Society members from over 300 parishes across the Archdiocese of Boston assembled. A large altar was erected upon which Cardinal Richard Cushing stood to deliver the keynote address on the subject of personal holiness.

Cardinal Cushing defined sanctity as "the union of the mind and heart with God," the purpose for which they were made, he states. Adding, "we were made in His image and likeness in order that the image might the more readily recognize the original; in order that the imitation might the more nearly approach the model."

This was not always so obvious, he shares, as originally God's commandments "were imprinted in the human heart," but man sinned. God then wrote down his commandments and gave them to Moses and, yet, man still sinned. Finally, he sent us Jesus Christ, who "spoke as God never could do before, to His fellow human beings, as man to man." It was in this form that it could simply be stated, "love God and love your neighbor," worship God directly and be a good neighbor through the works of mercy.

Settling upon the subject of his address, he emphasizes: "it is not that we should consider holiness and union with God in general, but personal holiness, the sanctification of each individual soul here present."

Cardinal Cushing immediately moves to a series of images that show how humankind has moved away from personal experiences which, though the words were spoken in 1953, remain relevant today.

"From birth till death we have grown accustomed to having what would ordinarily be personal work done for us by certain professionals," he claims, mothers now have babies in hospitals rather than at home, formulas nourish their children, and the children are sent to school as early as possible. "Before summer is over, we can hear a chorus of mothers saying, 'I'll be glad when school begins," he laments. And "moral instruction is presumably attended to by the churches," he adds, because at home no one talks to each other, but instead sit and listen to the radio or television."

He warns that "whatever merits or demerits of this life-long series of substitutions, it is likely to relax us into the attitude that somehow we can get substitutes to perform for us the fundamental duties of the Christian life."

He expresses his fear of complacency and instead calls upon each Catholic to become an apostle of Jesus Christ, urging them not to leave holiness to the clergy and religious alone. "Every Christian is called to be an apostle of Jesus Christ, not by Holy Order, but by Baptism," he says. At baptism, we are all called to obey the commands of God, not make sure someone else obeys them.

He gives further examples of complacency, having a Mass offered or knowing a Mass is being offered for a specific intention but not attending oneself. And while he admits no one knows better than he the value of monetary contributions to orphanages, schools, hospitals and other causes, these contributions lack a personal investment. A monetary contribution, while helpful, only makes up for the vast numbers who are not serving God and their neighbor, he believes.

He cites the personal nature of the kindness shown by the Good Samaritan, who personally cleaned and dressed the wounds of the man he found on the road, and allowed to ride his donkey, escorting him safely to an inn to recover.

"It is not enough to unload that which we 'cannot take with us' in the interests of the needy," Cardinal Cushing stated, "we must give our own soul, which we must take with us, to be sternly judged as charitable and Christlike, or selfish and diabolic, as the case may be."

"Why particularly each one of us was created, we do not know. This we do know, there must be a special reason why we were given the breath of life ... the general reason is that we be holy ... it is not a holiness to be worked out in distant places, any more than in distant centuries. It is here and now."

There is a misconception about vocations, he claims, that only the special few are called by God. But the laity can be called to do good as well, so "why should we hesitate to say that they have a vocation to do it? They may in fact be called by God to do a work for Him which, because of their peculiar position and circumstances in life, the clergy cannot do."

Cardinal Cushing concludes that he hopes his words about personal holiness will benefit those in attendance, stating that "there is no longer leisure for experiment, nor time for controversy. There is barely time for the 'one thing that is necessary' the most perfect obedience to the law of God."

- Father Thomas Ryan, CSP, directs the Paulist North American Office for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations in Boston.