Discord in the early Portuguese Catholic community

Throughout the 19th century, Boston's bishops regularly contended with a lack of priests, especially those who spoke a language other than English and could effectively communicate with Catholics recently arrived in New England. While meeting the challenges of this chronic problem was a trying task on its own, external pressures could add to the difficulty, as a letter to Archbishop John Williams reveals.

Though they arrived in smaller numbers than other Catholic immigrant groups, shortly after then-Bishop Williams was installed, he began searching for a Portuguese-speaking priest who could adequately serve the Portuguese Catholics living in the diocese. The first priest is believed to have arrived in New Bedford in 1866 but died in September of the same year. There was at least one, possibly two, who also had brief stays in the area until the arrival of Father Joao Ignacio, considered "the real founder of our Portuguese missions."

He is also referred to as Father Joao Ignacio d'Aravedo, or Azevedo da Encarnacao, and possibly other variations depending on the source. We will simply refer to him as Father Ignatius, as Archbishop Williams did.

Father Ignatius was sent by the Bishop of Angra, a diocese which encompasses the Azores, and began his ministry in New Bedford, arriving in January 1869. He celebrated Mass with the Portuguese Catholics at St. Mary Church, and began raising funds among the congregation, using it to purchase land on which would later stand St. John the Baptist, credited with being the first Portuguese parish in New England.

He left New Bedford for Boston in 1873, where, in June of that year, Archbishop Williams had purchased a former Baptist church on North Bennett Street in the North End of Boston for use by Italian and Portuguese Catholics. Though they now shared a church dedicated to St. John the Baptist, Father Ignatius shared the role of pastor with an Italian-speaking priest so they could each minister to their respective communities.

Interestingly, in "One Hundred Years of Progress," it states that Archbishop Williams had paid $25,000 for the church and gave the two congregations two years to raise money, at which time whichever raised the most towards paying for it would become the sole occupant. It continues that the Portuguese parishioners raised $12,500, compared with the $10,000 raised by the Italian parishioners, prompting the Italian congregation to establish St. Leonard of Port Maurice in 1876.

One might expect that, after making such a large contribution to secure the church for themselves, the Portuguese Catholic community might grow closer and thrive. Instead, it began to fracture. What exactly the problem was is unclear, some attribute it to the strained finances of maintaining the church without the contributions of the Italian parishioners, which is understandable after making such a large contribution to secure the church for their use.

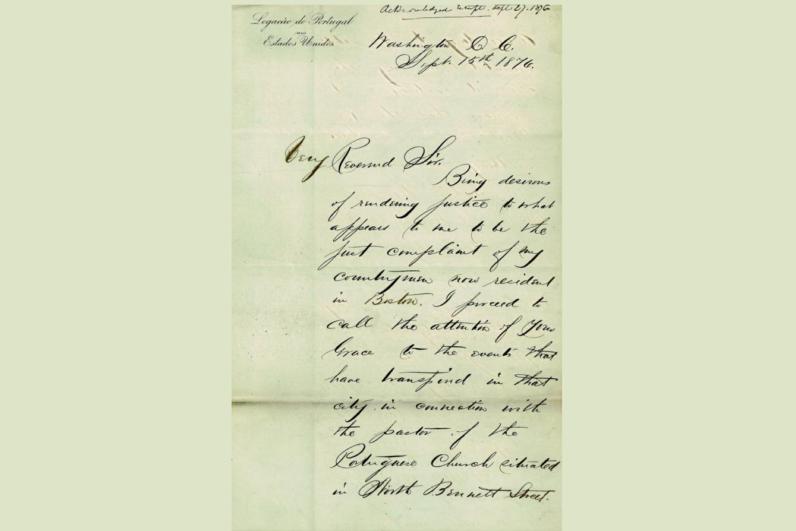

One other piece of evidence, which requires examination, is a letter in Archbishop Williams' papers from the Portuguese consul to the United States, Baron de Sant'Arma, insisting Father Ignatius was the problem and needed to be replaced. His letter, written to Archbishop Williams on Sept. 15, 1876, claims that Father Ignatius was dismissed from the parish he founded in New Bedford, was once again displaying his "peculiar temperament," that he invited an Irish priest to speak and who allegedly made derogatory remarks about the Portuguese people. The consul also claims that Father Ignatius told the congregation a previous consul was in hell, "an assurance that afflicted the minds of those who knew that gentleman."

The consul, writing from Washington, D.C., had received a petition signed by 88 members of St. John the Baptist declaring that if Father Ignatius was not removed, they would leave the parish and find another Catholic Church to attend, as some had already done. He reminds Archbishop Williams that the community has contributed "$10,000" to the parish and warns that, if the pastor was not removed, the results "will be the cause of much annoyance and scandal."

The authors of the "History of the Archdiocese of Boston" suggest that episodes such as this reveal that Trusteeism, or the administration of parishes by lay members, was something Archbishop Williams still had to contend with, despite its apparent decline in the preceding decades.

Though it is unclear from what evidence they drew their conclusions, the authors referenced above seem to favor Father Ignatius, claiming the Portuguese consul was causing the rift in an attempt to exert his authority on the Portuguese community of Boston; in the time afforded for this column, nothing was found to support or refute such a claim.

What we can deduce is that Father Ignatius retained the respect of Archbishop Williams, remaining as pastor of St. John the Baptist for two more years before, at his request, being allowed to depart for his home diocese. An entry by Archbishop Williams in the Episcopal Register dated Sept. 16, 1878, reads that Father Ignatius "leaves with the good will of all the good Portuguese's and his record in the diocese has always been that of a good and zealous priest."

Father Ignatius was succeeded by Father Henry Hughes, OP, a Welsh convert who had worked as a missionary in Europe and Africa, spoke 12 languages, and had been an interpreter at the First Vatican Council. He is credited with healing any lingering wounds among the congregation, enlarging the church and starting a parochial school in his eight years of service to the parish.

- Father Thomas Ryan, CSP, directs the Paulist North American Office for Ecumenical and Interfaith Relations in Boston.