Beyond the righteousness of the Scribes and Pharisees

Just as balloons can look designed to be popped, with the merest prick of pin, so do merely human ideals seem to beg for deflation.

And yet we need them. If you doubt that, start paying attention. The richest man in the world, an icon of success, Jeff Bezos, divorced his wife of 25 years, leaving her for a helicopter pilot who dresses in leather. He courted his new girlfriend with obscene texts, including pictures of his private parts, as the world discovered after his brother, or maybe it was his girlfriend, betrayed him to a tabloid newspaper. This great man, giving the world an example of folly and self-deception, went on to blame Donald Trump and foreign powers for the revelation, not acknowledging any blame himself. He even drew down into his web of deception the once great newspaper which he purchased.

Whatever his strengths, he's not a gentleman, I think we can grant, anymore than someone who brags that the best way to get women to like you is to grab them by ... well, we won't say.

The examples go on and on. In the face of them, we need not "civility" as people say, mere etiquette or politeness, but stronger stuff, some kind of ideal of how to live, and what to die for. We need a complete package, a code, a way of life, a flag that people can rally under, with exemplars and heroes. But here's the paradox: although we need such a high ideal of life, the ones that our philosophers and religious leaders have thought up -- which express a high ideal, one might say, of the merely human -- end up being either ludicrous or repugnant, often both.

Brad Miner's book, "The Compleat Gentleman," recently published in a revised third edition, argues that such an ideal is possible today only with a Christian inspiration, and only drawing deeply from ideals of chivalry.

The mentioned paradox was present from the start. Socrates was very attractive for devoting his life to seeking wisdom and exposing the ignorance of the elites of his day, right? But Aristophanes, probably with some reason, lampooned him and his followers for bad hygiene, uselessness in the world, and absurd self-importance. Aristotle has a famous portrait of "the magnanimous man" -- the great-souled man -- with many appealing traits. But when he concludes his description telling us that great personages like that should walk slowly, speak in a deep voice, appear to be unhurried, and take care not to be excitable, readers may wonder whether a description meant originally in earnest hasn't drifted into self-parody.

More recently, St. John Henry Newman gave his famous ideal of a gentleman. People often cite it, especially its line that "it is almost a definition of a gentleman to say he is one who never inflicts pain." There are many beautiful parts in Newman's description, such as this: "The true gentleman ... carefully avoids whatever may cause a jar or a jolt in the minds of those with whom he is cast; -- all clashing of opinion, or collision of feeling, all restraint, or suspicion, or gloom, or resentment; his great concern being to make every one at their ease and at home. He has his eyes on all his company; he is tender towards the bashful, gentle towards the distant, and merciful towards the absurd; he can recollect to whom he is speaking; he guards against unseasonable allusions, or topics which may irritate; he is seldom prominent in conversation, and never wearisome. He makes light of favours while he does them, and seems to be receiving when he is conferring. He never speaks of himself except when compelled, never defends himself by a mere retort, he has no ears for slander or gossip, is scrupulous in imputing motives to those who interfere with him, and interprets every thing for the best."

And yet Newman is wary of the ideal. The "gentleman" is a beautiful realization of how human nature might best be developed "apart from religious principle." But given such a standing, it can "distort the development of the Catholic (ideas)" for a person. It can just as well turn against holiness, he worries, as be put in the service of it.

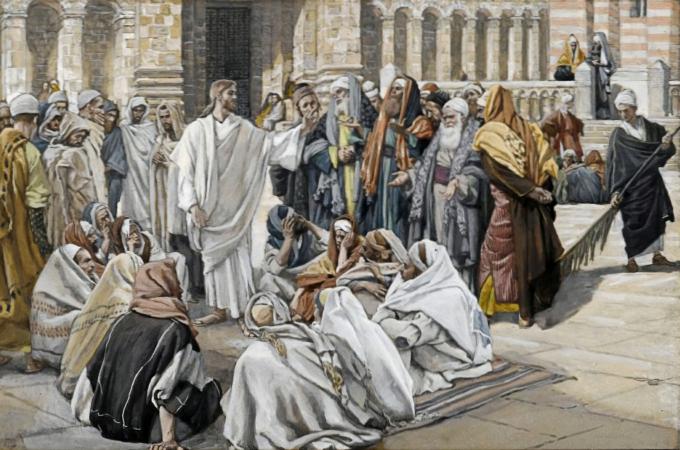

The best candidates for gentlemen in Our Lord's day -- read the glowing descriptions of them in contemporary authors -- were the Scribes and Pharisees, cultured men, who knew how to behave, and took care not to offend. But they saw a menace in Jesus from the start and plotted to destroy him. Was it typical Semitic hyperbole or a vision of the plain truth which led Our Lord to say that prostitutes were entering the Kingdom of God before them (Mt. 21:31)?

So, something more is needed for a complete and acceptable gentleman, and Miner's historically informed argument is that that element is chivalry. Miner's is a romantic thesis in the strict, sober sense. It's essential to chivalry that a man live as always prepared to die, like the heroes of Flight 93, with their "Let's roll!" But also that he be just. "The best men -- as warriors, lovers, and monks -- have always been just men," Miner concludes, "Of all the chivalrous attributes, honor is the greatest, because it brings the burden of justice into every moment of a man's life."

- Michael Pakaluk, an Aristotle scholar and Ordinarius of the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas, is a professor in the Busch School of Business at the Catholic University of America. He lives in Hyattsville, MD, with his wife Catherine, also a professor at the Busch School, and their eight children. His latest book, on the Gospel of Mark, is "The Memoirs of St Peter." His next book,"Mary's Voice in the Gospel of John," is forthcoming from Regnery Gateway.