Marking the Gospel of Mark with a fresh approach

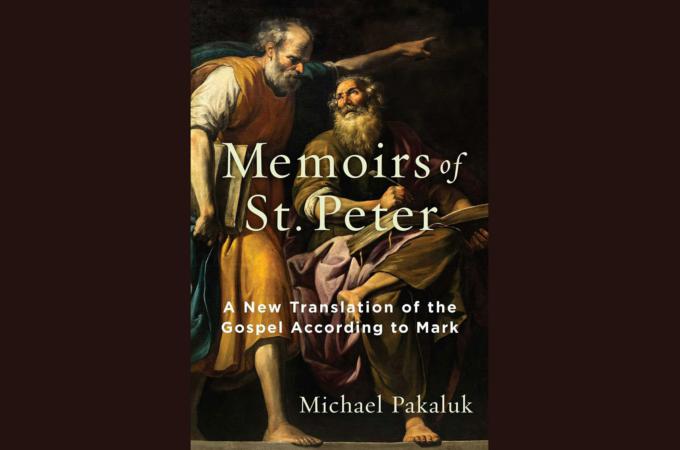

There's a new translation of the Gospel according to St. Mark, the shortest of the four gospels, entitled "The Memoirs of St. Peter." It's by a good friend of mine, Michael Pakaluk, who is also a columnist for The Pilot. Published in 2019 by Regnery Gateway, it has just been joined this year by his new translation of the Gospel according to St. John, entitled "Mary's Voice in the Gospel According to John." I can't wait to read the new volume, for his Gospel of Mark is superb.

Pakaluk provides an introduction which explains his approach to translating and commenting on Mark's Gospel, relying on the ancient tradition that Mark accompanied St. Peter and captured the immediacy and themes of Peter's first-hand preaching about the public life, death, and resurrection of Jesus, including Jesus' sayings and his miracles. He quotes Tertullian, for example, who wrote at the end of the second century: "The Gospel that Mark wrote may be affirmed to be Peter's, whose interpreter Mark was."

So, one of the features of this translation is to translate Mark's use of the original Greek historical present as an English present, so it oftentimes reads as if you are there while the events unfold. Here is Pakaluk's method explained in his introduction: "I am aware of three methods for drawing out the literal sense. In the first, the reader uses his imagination to picture as fully and acutely as possible what is recounted, just as a child listening to a story does. St. Ignatius of Loyola recommends this method in his 'Spiritual Exercises.' The second method appeals more to the heart. The reader takes on the role of someone in an episode of the Gospel and fosters the thoughts and emotions of that person. St. Josemaria Escriva is a great proponent of this method, as for example in his devotional book on the Holy Rosary. But here I follow a third method, which mainly engages the intellect. In this method, the reader is invited to puzzle over Scripture, to find it intellectually interesting, by considering the question, 'What must have things been like for the events recounted here to have taken place?'"

Michael Pakaluk is successful in reading and commenting on Mark's Gospel -- Peter's memoirs -- in this way. It causes one to approach afresh and consider anew Gospel passages that are familiar, sometimes too familiar to be freshly considered.

Here's his translation from chapter 7 of Jesus' cure of the deaf and dumb man: "They bring him a man who was deaf and dumb. They beg him to place a hand on the man. So, leading the man by himself, away from the crowd, he placed his fingers into his ears. Spitting, he touched his tongue. Looking up to heaven, he sighed deeply. He says to him, 'Eph-phatha.' (That is, 'Be opened.') The man's ears were opened, the binding on his tongue was loosed, and he spoke fluently." The translation conveys a sense of immediacy, a certain "you are there" quality.

Here's his commentary on Jesus' sigh: "This is not for the man's benefit: he can't hear yet. Nor for the crowd's: they were too far away to hear it. Jesus' sigh is simply a spontaneous expression of his mercy and pity. Again, Peter is conveying what it was like to be there." As to the Aramaic word 'Eph-phatha," "Here we have once again Peter's 'sound recording' of what it was like to hear Christ speak. Note that Jesus does not heal the man by touch alone but by a word that gives the interpretation of the touch. The seven sacraments are like this. They involve a tactile gesture, like washing or anointing, and yet the imparting of grace requires the added verbal dimension, which gives the interpretation of the action and relates to the action as form to matter."

This is biblical translation and interpretation of a high order, nourishing the mind with spiritual insight and wisdom in full accordance with the Church's rich tradition. I can't recommend it too highly, but judge for yourself.

- Dwight G. Duncan is professor at UMass School of Law Dartmouth. He holds degrees in both civil and canon law.