Conflict on the Passamaquoddy Reservation

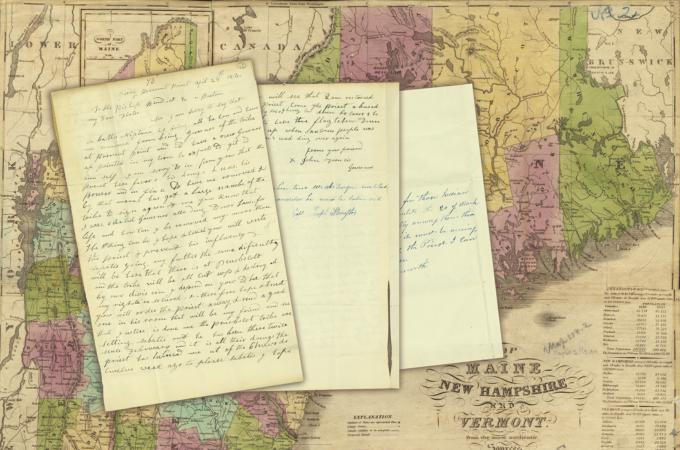

On April 28, 1840, Gov. John Francis Neptune wrote to Bishop Benedict Fenwick of Boston from Pleasant Point, Maine, a town on the Passamaquoddy Reservation. He requested the bishop's aid in a struggle to retain his place as leader of the tribe, and the traditional lifestyle he embodied, over those who favored a modern communal lifestyle.

Gov. John Francis Neptune was the son of the late Chief Francis Joseph Neptune, who had allied the Passamaquoddy with the colonists during the American Revolution. Disappointed at being a non-entity in the Treaty of Paris (1783), he subsequently negotiated with the State of Massachusetts, to which Maine then belonged, and in return for their loyalty the Passamaquoddy secured ownership of land, which extended through parts of Maine and into Canada. The resolution was passed by the Massachusetts Legislature on Sept. 29, 1794.

Chief Francis Joseph continued to serve as chief (or, now, governor of the reservation) until his death, prompting a vote for his successor in 1834. Traditionally, the chief's eldest son or a close male relative would succeed him and remain in that role until the end of his life. Though this was the general pattern of succession, the choice of a new chief still had to be approved by the tribe and, in this instance, there was strong opposition to John Francis succeeding his father.

John Francis, like his father, displayed exemplary skills, values and other qualities that made him an ideal successor within the context of a traditional hunting lifestyle. However, those in opposition had largely settled in towns on the reservation and favored this communal lifestyle and the benefits it offered, among them access to educational and religious instruction. They sought a leader who could effectively communicate with those outside of the reservation, help their towns grow, and advocate on their behalf.

John Francis had enough support to garner a majority of the votes and succeed his father as governor; however, the opposition and their preferred candidate, Sabattis Neptune, would continue to challenge his leadership for nearly 20 years.

In his letter to Bishop Fenwick, Gov. John Francis writes that Sabattis is "doing all he can and have me removed from being governor of the tribe at Pleasant Point and to have a new governor appointed in my room he aspects to git it himself." Furthermore, he accuses the Catholic priest assigned to Pleasant Point, Father Louise-Edmond DeMillier, of being partisan: denying John Francis access to the church and encouraging support of his rival, Sabbatis. He also claims that Father DeMillier struck his wife, knocking her down.

He reminds Bishop Fenwick that his position of governor is for life, asking "how can I be removed any more than a king can be(?)" He also asks that the bishop write Father DeMillier to respect his place as the duly-elected governor. Finally, he pleads that he depends on the bishop for security, and "therefore hope and trust you (Bishop Fenwick) will order the priest away and send a good one in his room (sic.) that will be my friend and see that justice is done me . . ."

There are two notes, which were added to the letter in transit. One is signed by Captain Joseph Stoneflos, most likely the bearer of the letter, who wrote that "if the Priest stays here two weeks longer we shall have fighting among ourselves he must be taken [?] away."

The second note is from James Farnsworth, who noted "Sir, I have been the agent for those Indians for the last seven years until the 20 of March last; there is more difficulty among them than I have ever known before. It must be owing to the bad management of the Priest, I can assign it to no other cause."

If Bishop Fenwick took any steps to rectify the situation, it did not include removing Father DeMillier, who remained on the reservation until his death on July 23, 1843. The bishop may have had little choice due to the scarcity of priests in the diocese, and even fewer who were qualified to serve on the reservation. Following Father DeMillier's death, it would be some time until another resident priest was assigned there, the reservation instead receiving regular visits from priests based in Eastport, Maine.

The conflict seems to have been resolved with a treaty enacted by the State of Maine on Feb. 28, 1852. It allowed for Gov. John Francis to remain in his position at Pleasant Point for the remainder of his life. It simultaneously provided for a second governor to be elected and based at Indian Township, also within the reservation, who would be elected in four-year terms.

It continued that upon the death of Gov. John Francis, the Passamaquoddy would vote whether they should continue with two governors, one at each location, or live under just one based at Indian Town. It was decided upon his death in 1875 to continue with two governors.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.