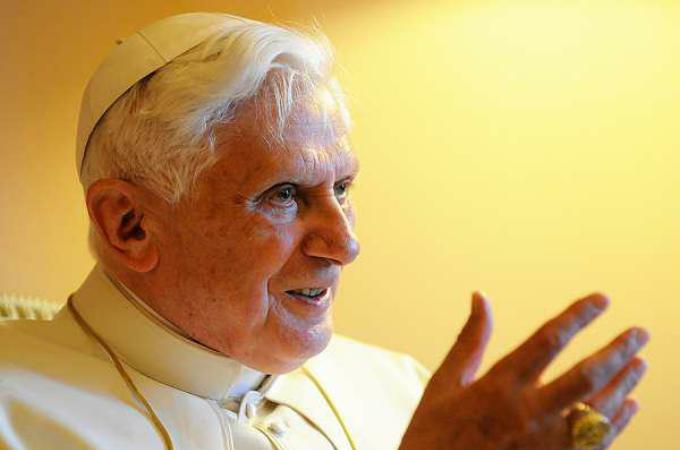

What does Benedict XVI actually say in new book on priestly celibacy?

Vatican City, Jan 14, 2020 CNA.- In his chapter in a new book on priestly celibacy, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI says a historical understanding of the priesthood in the Old and New Testaments makes it clear that celibacy is an ontological, rather than optional, part of the Catholic priesthood.

“From the Depths of Our Hearts” is set to be released in French this week and in English next month. The book consists of chapters written individually by Benedict and Cardinal Robert Sarah, prefect of the Congregation for Divine Worship, as well as a joint introduction and conclusion.

Controversy has shrouded the book since its publication was announced Jan. 12, largely over disagreement about how much Benedict contributed to the book's introduction and conclusion, and whether he gave permission for publishers to identify him as a coauthor of the text.

While that controversy is ongoing, less discussed is what Benedict XVI actually said in the chapter of the book that the pope emeritus did write.

What did Benedict XVI say in his chapter of the book?

At the core of his writing is an argument that the sexual abstinence that was merely “functional” for the priests of the Old Testament has been transformed into something “ontological” in the priesthood of the New Covenant, according to a draft text of the book seen by CNA.

Benedict’s chapter examines the history of the priesthood in the Old and New Testaments, saying that a proper understanding of the nature of the priesthood is crucial in answering contemporary questions about priestly celibacy.

“At the foundation of the serious situation in which the priesthood finds itself today, we find a methodological flaw in the reception of Scripture as Word of God,” Benedict says.

Abandoning a Christological interpretation of the Old Testament has led to a “deficient theology of worship” among many modern scholars, who fail to recognize that Jesus fulfilled the worship owed to God, rather than abolishing it, he continues.

Looking at the history of the priesthood in the Old Testament, Benedict says that “the relation between sexual abstinence and divine worship was absolutely clear in the common awareness of Israel.”

He notes that the priests of Israel were required to observe sexual abstinence during their time that they spend leading worship, when they were “in contact with the divine mystery.”

“Given that the priests of the Old Testament had to dedicate themselves to worship only during set times, marriage and the priesthood were compatible,” he says. “But because of the regular and often even daily celebration of the Eucharist, the situation of the priests of the Church of Jesus Christ has changed radically.”

Since the entire life of the priest in the New Covenant is “in contact with the divine mystery,” he says, it demands “exclusivity with regard to God” and becomes incompatible with marriage, which also requires one’s whole life.

“From the daily celebration of the Eucharist, which implies a permanent state of service to God, was born spontaneously the impossibility of a matrimonial bond. We can say that the sexual abstinence that was functional was transformed automatically into an ontological abstinence. Thus its motivation and its significance were changed from within and profoundly.”

Benedict’s text seems focused on the Latin Catholic Church; many Eastern Catholic priests do not celebrate Mass daily, and the former pope does not address specifically theology of Eastern Catholic married priests.

The pope emeritus rejects the idea that priestly celibacy is based on a contempt for human sexuality within the Church. He notes that this claim was also dismissed by the Church Fathers, and that the Church has always viewed marriage as a gift from God.

“However, the married state involves a man in his totality, and since serving the Lord likewise requires the total gift of a man, it does not seem possible to carry on the two vocations simultaneously,” he says. “Thus, the ability to renounce marriage so as to place oneself totally at the Lord’s disposition became a criterion for priestly ministry.”

Just as the priests from the Tribe of Levi renounced ownership of land, priests in the New Covenant renounce marriage and family, as a sign of their radical commitment to God, he says.

This is seen in the Psalm prayed when a man entered the clergy before the Second Vatican Council, he says: “The LORD is my chosen portion and my cup; you hold my lot. The lines have fallen for me in pleasant places; yes, I have a goodly heritage.”

Benedict concludes with a reflection on the words of John 17:17-18: “Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth. As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world.”

He says these words struck him deeply on the day before he was ordained a priest, and led him to reflect on the lifelong calling of a priest to continually unite himself to Christ and renounce “what belongs only to us.”

“Thus, on that eve of my ordination, a deep impression was left on my soul of what it means to be ordained a priest, beyond all the ceremonial aspects: it means that we must continually be purified and overcome by Christ so that He is the one who speaks and acts in us, and less and less we ourselves,” the pope emeritus says.