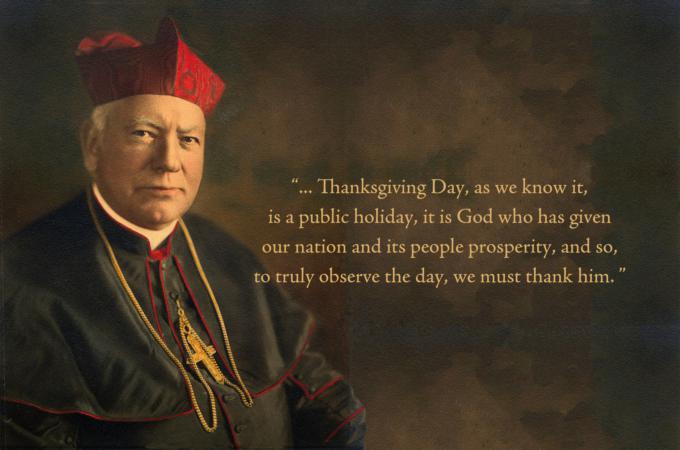

Cardinal O'Connell's Thanksgiving sermon

In the published writings of Cardinal William H. O'Connell, archbishop of Boston from 1907 to 1944, is an undated Thanksgiving sermon in which he speaks upon the meaning of the holiday and what it means to be an "Ideal Citizen."

In the first part of the sermon, Cardinal O'Connell attempts to connect the civil holiday to its religious origins, commenting on the Christian character of the country and the religious context in which days of thanksgiving were historically observed. Although he acknowledges that Thanksgiving Day, as we know it, is a public holiday, it is God who has given our nation and its people prosperity, and so, to truly observe the day, we must thank him. He commends the president for inviting "citizens of the republic to turn aside for awhile from their worldly occupations and interests and cares, in order that congregating in their various houses of worship they may return thanks to the Giver of all good gifts."

Cardinal O'Connell then expresses his obligation to speak about some subject of public interest on the day and has chosen to speak about what makes the "Ideal Citizen."

"It has been said that ideas rule the world," he says, but "this is not strictly accurate. It is ideals by which the world is governed." He elaborates upon this point, stating that ideas are inactive, but ideals are embodied by the people of a nation and put into action, given life, made a reality.

A nation is the sum of its individuals, he argues, and so if our ideals are base and mean, so, too, will the nation be. If they are right and just, the nation will be so in the eyes of God and will persist with strength and stability. Therefore, the fate of the nation rests with everyone, from the most powerful leader to the humblest laborer, a share in this responsibility rests upon each one of us. He continues that "God has given to each his special sphere, his particular work to do; and the work of each well done fits into the design of the whole plan, and completes the whole."

But what is the "true ideal" of a nation, Cardinal O'Connell asks his audience. He does not believe it is warfare and provides a list of ancient civilizations that embraced this concept and eventually perished by it. In his opinion, the United States has entered most conflicts in the name of self-defense and does not measure itself by the number of battles won or enemies slain.

Cardinal O'Connell likewise warns of making wealth the national ideal; not necessarily the acquisition or possession of wealth, but the worship of wealth. Nations that idolize wealth often present a façade of success, yet squalor and decay linger underneath. He states that "Rome was never so strong as when her Dictators came from the ploughshare, never so weak as when her Emperors built palaces of gold."

So, if our own nation idealizes neither warfare nor wealth, "can we not find somewhere an ideal that will make the perfect citizen?" We are unique, he says, because, "In a land like ours where every citizen is king, where the whole prosperity of a people depends upon the character of its citizens, where the lowest by birth may rise highest in position, there is need more than elsewhere in all the world of an ideal which be alike effective in its operation and practical in its embodiment."

His answer is that Catholic ideals create ideal citizens. Catholics are disciplined in their respect for authority, whether God or a government official, and can obey laws, whether it be the Ten Commandments or the Constitution. These are the principles that create a firm foundation upon which a government can be built, he believes.

There is much more to this sermon, particularly the numerous examples Cardinal O'Connell cites to support each point, but this overview addresses most of the major themes. The strong and authoritative nature of his words can largely be attributed to the style of public speaking at the time which called for strong, confident, statements and opinions.

While this text is undated, the collection of writings was published in 1911, coinciding with events that would lead to the outbreak of World War I in the summer of 1914.

When he speaks of warfare as an ideal and warns that those nations that embrace it will perish by it, he is probably expressing concern over the militarization of Europe, and the race to arm with modern weapons and train millions of civilians as conscripts.

His point on Catholic ideals probably holds two meanings. On a local and national level, it confronts the prejudice that Catholics were loyal to the pope, and by following him could not exercise the freedom of thought required by citizens in a democracy. Likewise, being Catholic had prevented many from holding public office, though that was changing.

On the world stage, socialism and anarchism were two growing movements, and he alludes to these in the text, and championing Catholics' obedience to authority and law seems to be directly combatting these ideals.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.