Newman -- Prophet of the Great Apostasy

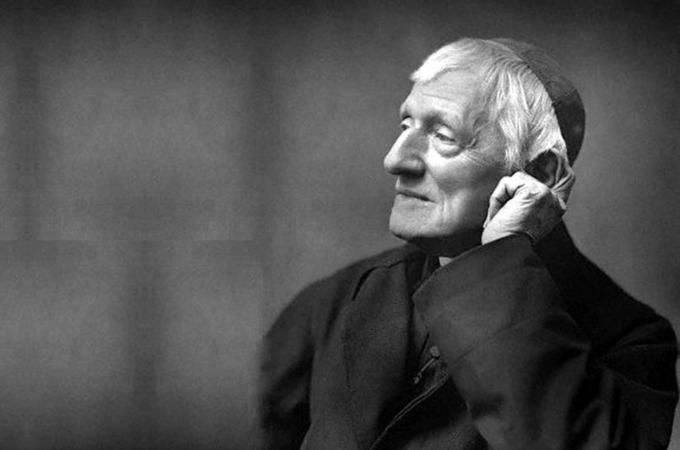

A "biglietto," in Italian, is a ticket or card. In May 1879, a messenger from the Vatican Secretary of State brought a message to a 78-year-old English priest, written on a biglietto, that the priest had been created a cardinal that morning by the recently elected Pope Leo XIII. The papal messenger was received in the Palazzo della Pigna, near the Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva, which you may know if you have visited Rome. The priest was of course John Henry Newman. He had written his masterwork, "An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent," nine years earlier, and regarded himself as coming to the end of his life as a writer. The speech which he gave on that occasion, known from that day onward as his "Biglietto Speech," was effectively his last word.

In the speech, Newman looks back over his life and identifies the evil which has been his main preoccupation. He then describes a world in which this evil seems triumphant -- and it is our world today, foreseen in the Victorian era by this great saint.

"I rejoice to say, to one great mischief I have from the first opposed myself. For thirty, forty, fifty years I have resisted to the best of my powers the spirit of liberalism in religion. Never did Holy Church need champions against it more sorely than now, when, alas! It is an error overspreading, as a snare, the whole earth," he begins his speech.

What does he mean by liberalism? It is "the doctrine that there is no positive truth in religion, but that one creed is as good as another, and this is the teaching which is gaining substance and force daily. It is inconsistent with any recognition of any religion, as true. It teaches that all are to be tolerated, for all are matters of opinion. Revealed religion is not a truth, but a sentiment and a taste; not an objective fact, not miraculous."

He spells out some of the consequences. Religion becomes merely subjective and private. It is no longer the universally accepted dictum, as it was when he was a child, that "Christianity is the law of the land." "Hitherto, it has been considered that religion alone, with its supernatural sanctions, was strong enough to secure submission of the masses of our population to law and order," he says, but "now the Philosophers and Politicians are bent on satisfying this problem without the aid of Christianity."

He then describes a new and threatening Great Apostasy. We may read it wondering "What could be wrong? That's how things should be." For it is our status quo.

"Instead of the Church's authority and teaching, they would substitute first of all a universal and a thoroughly secular education, calculated to bring home to every individual that to be orderly, industrious, and sober, is his personal interest." Observe that he attacks the idea that "self-interest rightly understood," which seems sufficiently good to us, should be the basis of our action.

"Then, for great working principles to take the place of religion, for the use of the masses thus carefully educated, it provides -- the broad fundamental ethical truths, of justice, benevolence, veracity, and the like; proved experience; and those natural laws which exist and act spontaneously in society, and in social matters, whether physical or psychological; for instance, in government, trade, finance, sanitary experiments, and the intercourse of nations. As to Religion, it is a private luxury, which a man may have if he will; but which of course he must pay for, and which he must not obtrude upon others, or indulge in to their annoyance."

He says that, in the case of England, the "liberalistic theory" is becoming dominant because of religious pluralism; also, because some religious thinkers believed that Christianity would be more pure if completely separated from the state; but mainly because there is much in the theory which is attractive -- "not to say more, the precepts of justice, truthfulness, sobriety, self-command, benevolence."

But therein lies a trap. "It is not till we find that this array of principles is intended to supersede, to block out, religion, that we pronounce it to be evil. There never was a device of the Enemy so cleverly framed and with such promise of success." "I lament it deeply," Newman says, "because I foresee that it may be the ruin of many souls."

He concludes his speech with acts of faith and hope. Of faith: "I have no fear at all that it really can do aught of serious harm to the Word of God, to Holy Church, to our Almighty King, the Lion of the tribe of Judah, Faithful and True, or to His Vicar on earth. Christianity has been too often in what seemed deadly peril, that we should fear for it any new trial now." Of hope: God saves his people in many ways, "Sometimes our enemy is turned into a friend; sometimes he is despoiled of that special virulence of evil which was so threatening; sometimes he falls to pieces of himself; sometimes he does just so much as is beneficial, and then is removed."

What is our task in the trial? To seek holiness in daily life. "Commonly the Church has nothing more to do than to go on in her own proper duties, in confidence and peace; to stand still and to see the salvation of God."

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.