The Temperance Movement in 19th century Boston

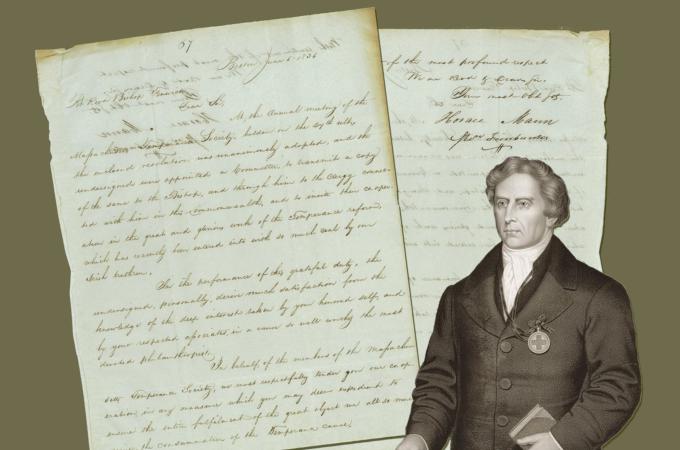

In the papers of Bishop Benedict J. Fenwick of Boston is a letter dated June 6, 1836, from Horace Mann, at the time a Massachusetts Representative from Boston, conveying a resolution unanimously passed by members of the Massachusetts Temperance Society. The enclosed resolution reads as follows:

"That it afford us peculiar pleasure to know that a Temperance Society has recently been formed in this City by our Irish brethren on the highly praiseworthy principal of ... freedom from all sectarian difference in religion."

While Mann is renowned for his work in education, he also supported other social causes, which came to the fore in antebellum American society, particularly the abolition of slavery and temperance. In the letter, Mann, writing on behalf of the society, offers its "cooperation in any measure which you may deem expedient to ensure the entire fulfillment of the great object we all so much desire, the consummation of the Temperance cause."

Though there were proponents of temperance during the late 18th century, it did not receive widespread support until the 19th. The Massachusetts Temperance Society, from which Mann writes, was founded as the Massachusetts Society for the Suppression of Intemperance in 1813, preceding the founding of the American Temperance Society, also in Boston, in 1826.

Many of the early societies were predominantly Protestant, but Catholics began to join soon after. Though it contained both Catholic and Protestant members, one of the early examples was the Irish Temperance Society, founded in Boston in 1835, and is most likely what Mann is addressing in his letter. Starting in 1838, Catholics took up the issue in greater numbers after being inspired by the work of Capuchin Father Theobald Mathew in Ireland, who that year started his campaign advocating for total abstinence from alcohol. The attention he received in the United States only increased as his followers, already pledged to abstain from alcohol, arrived in the United States in large numbers as they fled widespread famine at home.

The movement was officially sanctioned by the Catholic Church when the Fourth Provincial Council of Baltimore (1840) encouraged parishes to form their own societies, which inevitably placed Catholic priests in leadership roles. With Bishop Fenwick's blessing, pastors throughout the then Diocese of Boston administered the pledge of temperance to parishioners, and The Pilot eagerly reported the numbers and shared inspiring stories of individuals whose lives were improved through abstention.

As diocesan historians have commented, "almost for the first time Catholics and Protestants appeared to have found one moral crusade on which they could combine, and there was a brief period of what might also be called fraternization." Societies marched in parades together, held joint meetings, and Protestant clergy and Catholic priests visited each other's churches to speak about temperance and administer the oath.

Momentum continued to grow throughout the 1830s, reaching its height during the early 1840s, and then began to ebb. While the movement bridged religious divides, the relationship between groups advocating for responsible use of alcohol and those favoring total abstention became strained. There were also calls for legislative action, leading to laws in Massachusetts controlling the sale of spirits and prohibition in Maine, to name a few, but it is suggested this evolution from social into a political issue may have diminished the enthusiasm of some reformers.

Although after the perceived height of the movement, a highlight was certainly Father Mathew's visit to the United States in 1849. His itinerary included staying several days in Boston, where he was paraded through the streets and spoke at several large gatherings, administering the oath of abstention to thousands, before continuing to visit other cities throughout the state.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.