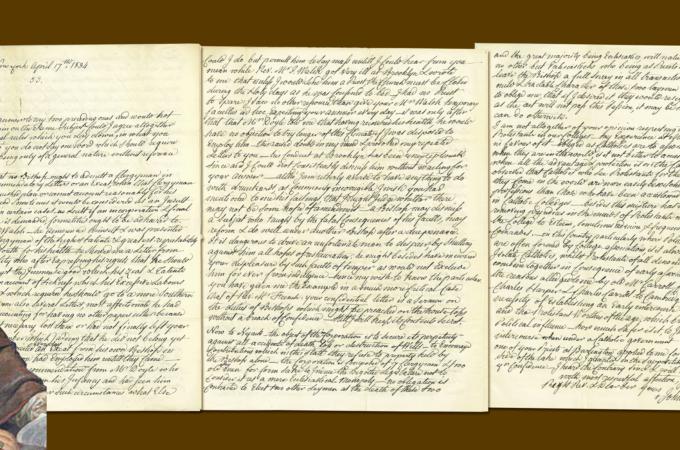

A letter from Bishop John DuBois of New York

On April 17, 1834, Bishop John DuBois of New York wrote to Bishop Benedict Fenwick of Boston. He starts by discussing the need to properly vet visiting priests; his trouble incorporating a seminary in Nyack, New York; and continues a debate about whether Protestants should be allowed to attend Catholic colleges.

Bishop DuBois first conveys the importance of properly reviewing the qualifications of visiting priests, stating that "it is generally true that no bishop ought to admit a clergyman in his diocese without commendatory letters or an exeat, taken that clergyman has not held a distinguished place or cannot account reasonably for his having no papers." He admits it can sometimes be insulting to ask for documentation, but bishops must adhere to formalities before allowing a priest to serve in their diocese.

He provides as an example the case involving a "Mr. Walsh," who was presented to him by a "Mr. Doyle" as a priest of "the highest talents and greatest respectability" on his way south to a region where the climate would improve his poor health. Mr. Doyle claimed to know Mr. Walsh since childhood, they were able to present several letters exchanged with Bishop Fenwick and one from a Boston physician as evidence of his need to seek a healthier climate.

While he awaited a letter of recommendation from Bishop Fenwick, Father John Walsh wrote from St. James, Brooklyn, that he had taken ill, and unless a priest could be sent there would be no Mass on Holy Days. With no other priest to send, Bishop DuBois sent the newly arrived Mr. Walsh. "What else could I do but permit him to say mass until I could hear from you," Bishop DuBois writes.

Soon after this episode, Mr. Doyle informed Bishop DuBois that Mr. Walsh recovered his health and would remain in New York if the bishop desired, but this raised the latter's suspicions, and he continued to write Bishop Fenwick urging a reply about the qualifications of Mr. Walsh. He apologizes to Bishop Fenwick for writing so many times but relates that Mr. Walsh's conduct in Brooklyn was "unexceptional," and he did not feel he could leave the priest's offer to serve unanswered for so long.

The answer finally arrived but did not endorse Mr. Walsh, and Bishop DuBois writes that "altho' I am utterly averse to have anything to do with drunkards as commonly incorrigible, I wish you had mentioned to me his failings, that I might judge whether there may not be some hope of amendment..." He agrees Bishop Fenwick was right to dismiss the priest but also expresses sympathy, and believes that "after due penance" the priest may recover and succeed under another bishop's guidance. "It is dangerous to drive an unfortunate man to despair, by shutting against him all hopes of restoration," he writes, and asks Bishop Fenwick for more specifics so that he may try to help Mr. Walsh.

After relating this episode, Bishop DuBois changes subjects, this time to the incorporation of a seminary in Nyack, New York. The bishop previously succeeded at Mount Saint Mary's College and Seminary in Emmitsburg, Maryland, simultaneously serving as president, treasurer and professor. In New York, laws made it difficult to incorporate and ensure that ownership could be retained by the diocese, specifically, the deed could not be in the bishop's name alone. To comply, he set up a trust consisting of himself, seven clergyman, and two older lay men. The priests were "removable at will" he relates, and the two laymen only joined as a favor to him, so it did not appear as solely an ecclesiastical institution, and they offered to resign at any time. If necessary, these steps could be taken to "leave the Bishop a full sway in all transactions."

Bishop DuBois closes his letter stating that, contrary to Bishop Fenwick's position, he believes Protestants should be allowed to attend Catholic colleges. His reasoning is that both will interact in the outside world, so the more familiar they become, the more agreeable will their relationships be afterward. Familiarity, he claims, will remove prejudices and classmates will learn to esteem one another. He also emphasizes that political connections are often formed while attending college, and it would not be wise for Catholics to isolate themselves when they might mutually benefit by developing relationships with Protestants.

Sadly, the seminary at Nyack, New York, was short lived. It was destroyed by a fire the same year this letter was written and, uninsured, nothing was salvaged from the wreckage. Correspondence between the two bishops does not appear in Bishop Fenwick's papers again until 1836, when four letters discuss the possibility of reestablishing the seminary at Nyack but this, and all subsequent attempts by Bishop DuBois, did not yield results.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.