Pope Francis' Letter to the U.S. Bishops

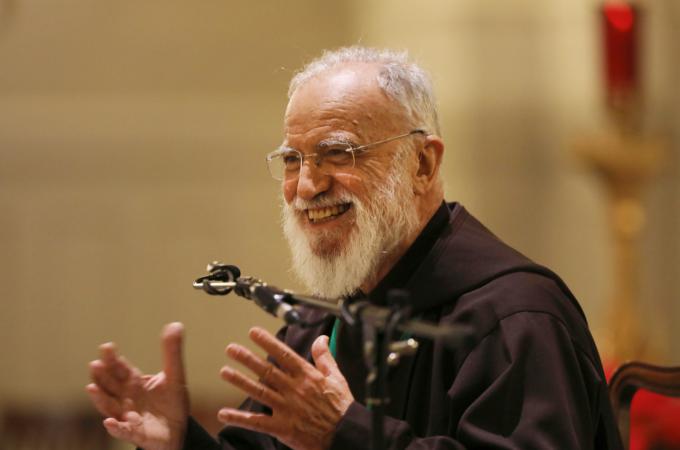

On January 1, Pope Francis wrote an extraordinary eight-page letter to the bishops of the United States as they were preparing to convene at Mundelein Seminary north of Chicago for a retreat with the preacher to the papal household, Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa. The retreat was suggested by Pope Francis to the leaders of the U.S. Bishops Conference when they met with him in Rome in September about steps to respond to the sexual abuse crisis plaguing the Church in our country.

The pope revealed at the beginning of the missive that his original intention was to accompany the bishops "personally" for several days of the retreat, but that, for logistical reasons, he was unable to fulfill that desire. Instead, he wrote the letter "to make up for that journey that could not take place" and in order to be "one with you during these days of spiritual retreat." Both the original desire and the length of the letter show that what is happening in the U.S. is not peripheral to the Holy Father's concerns, but something he considers a priority.

In the letter, he shared some of his own prayerful discernment as to the nature of the crisis and about the proper way to remedy it, hoping that the bishops would bring it to their prayer during retreat. For someone who has routinely and humbly declared, both before and after his election, that his "first discernment" is often erroneous, the letter was surely not meant to end conversation but to begin and nourish it. This is a prayerful conversation -- with the Lord and with other members of the Church -- that every American Catholic and all those interested in the reform of the Church should similarly enter.

Pope Francis makes five main points in his reflections.

The first is that the most profound response to the crisis must be spiritual. It must be done together with the Lord, having listened to him in prayer, not just as individuals as his body the Church. The temptation, Pope Francis said, is to focus primarily and hastily on administrative actions, new policies and procedures, and improved flow charts, as if new procedures and human procedures alone are what's required. He said that such things "can be helpful, good and necessary," but, if the crisis is reduced to an "organizational problem," it would not be grasped and dealt with adequately. Everything the Church does, he says, must have the "flavor of the Gospel," something, in other words, the Lord himself would do. The remedy must involve metanoia, he states, a conversion that extends also to the way those in the Church pray, handle power and money, exercise authority and relate to each other. Otherwise our well-structured and organized efforts "will lack evangelical power."

He says that bishops must be more than mere administrators, but those who can "teach others to discern God's presence in the history of his people." The Church's "primary duty is to foster a shared spirit of discernment," to help the whole Church "dare to come together, on our knees, before the Lord" and his sufferings on the Cross, so that the we might recognize that Christ is still with us, calling us to conversion and strengthening us to do the hard work necessary to cleanse the Church for which he died.

Obviously, to be capable of this, bishops must be good, moral, prayerful men who live the faith, not those living a double life as we saw in the case of former Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, or those who don't love their flock enough to protect them from known predators.

Pope Francis is suggesting that many of us might be looking for the Lord's voice in the "tempest or the earthquake," rather than in a gentle whisper, and, as urgent as addressing the crisis is, even more urgent is making sure we hear the Lord so that we will do whatever "the Lord best determines." Otherwise, Pope Francis warns, "the cure" may become "worse than the disease."

The second point is about the multivalent nature of the crisis that the Church is facing. It involves, he says, "abuse of power and conscience and sexual abuse on the part of ordained ministers, male and female religious and lay faithful." It also involves not only the "poor way" that those "sins and crimes" have been handled, but also the "efforts to deny or conceal" them, a cover-up mentality that "enabled them to fester and cause even greater harm." He doesn't explicitly mention the many questions and concerns about the McCarrick situation, and how he was able to rise in the hierarchy and remain in increasingly prestigious positions despite his sexual abuse of seminarians and minors, but it is possible to understand them as described by the sexual abuse, abuse of power and cover-up mentality he does name.

The third point is about the lack of unity that Pope Francis thinks may be a worse and longer-lasting scandal than the abuse and malfeasance. He describes "tensions, conflicts and disputes," "contradictions," "division and dispersion," "recrimination, undercutting and discrediting," "gossip and slander," "hatred and rejection" that have "deeply affected the communion of bishops and generated not the sort of health and necessary disagreements and tensions found in any living body."

It is somewhat to be expected that when deep corruption is exposed, those not implicated in it want to root it out completely, and can be susceptible to bringing longstanding concerns to the table all at once, with frustration and anger that can truly harm the familial bonds that are meant to exist within the Church. He warns that the "enemy of human nature," the devil, is trying to exploit the scandals to divide the Church for whose unity Christ prayed during the Last Supper, by leading bishops and faithful in the Church to attack each other rather than the problems of the scandals and the devil who rejoices in them. This "lack of unity, division and dispersion" are among the "greatest temptations" those in the Church face and Pope Francis urges the Church in the U.S. to focus squarely on remedying it, so that the bishops and the Church they guide can more concertedly battle the situation of infidelity and abuse.

Fourth is the crisis of credibility in the Church. He stresses that renewed credibility will not come from statements, new policies, marketing strategies or individuals' own personal or collective good name, but ultimately from the renewal of the credibility of the unity of the Church, what he terms a "united body that, while acknowledging its sinfulness and limitations, is at the same time capable of preaching the need for conversion." The restoration of credibility will come, in other words, from the Church's behaving as she always should have been behaving, something that involves not only hatred for sin out of love for God and sinners, but also profound unity flowing from the fact that God is our Father and Jesus entered our world to found a family comprised of those who hear his word and observe it.

This connection between unity and credibility is ever timely. There are many who do not realize that as they attack the credibility of bishops or priests whom they think are part of the problem -- or even attack the Holy Father -- they are undermining the authority of every bishop and priest and the whole Church. Constructive fraternal or filial criticism on particular points is one thing. All-inclusive acerbic attacks are another. The Church is meant to be the "sign and instrument of communion with God and of the unity of the entire human race," Vatican II teaches, and when we lack such unity, we scandalously obscure God and who we really are as his sons and daughters. "The greatest service [the Church] offers," Pope Francis insists, is this service of unity.

The fifth point is about the need for real and affective fraternal communion among bishops and within the whole Church, which is not just the absence of fomented division, but a concerted effort to unite each part to the whole. There are several elements to this effort: Praying for and with each other. Listening to each other. Giving and receiving help from each other. Working together. Suffering with each other. Exercising authority in constant reference to the universal communion of the Church. Proper spiritual fatherhood, conscious of the feelings and disheartenment of God's people. Constant conversion. And Mary's help, which helped sustain the unity of the first disciples.

That's the communion Pope Francis is praying for that will fortify the Church to eradicate the abuse. That's the communion he is hoping that the bishops and faithful of the Church in the U.S. will discern they need as the gift from God who wants to help rebuild his Church as a communion of holiness.

- Father Roger J. Landry is a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, who works for the Holy See’s Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations.