Tolkien, Chesterton and the adventure of mission

There is a common, and I'll admit somewhat understandable, interpretation of J.R.R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings trilogy that sees the great work as a celebration of the virtues of the Shire, that little town where the hobbits dwell in quiet domesticity. Neat, tidy hobbit holes, filled with comfortable furniture, delicate tea settings, and cozy fireplaces are meant, this reading has it, to evoke the charms of a "merrie old England" that existed before the rise of modernity and capitalism. As I say, there is undoubtedly something to this, for Tolkien, along with C.S. Lewis and the other members of the Inklings group, did indeed have a strong distaste for the excesses of the modern world.

However, I'm convinced that to see things this way is almost entirely to miss the point. For the ultimate purpose of Lord of the Rings is not to celebrate domesticity but rather to challenge it. Bilbo and Frodo are not meant to settle into their easy chairs but precisely to rouse themselves to adventure. Only when they leave the comforts of the Shire and face down orcs, dragons, goblins, and finally the power of evil itself do they truly find themselves. They do indeed bring to the struggle many of the virtues that they cultivated in the Shire, but those qualities, they discover, are not to be squirreled away and protected, but rather unleashed for the transformation of a hostile environment.

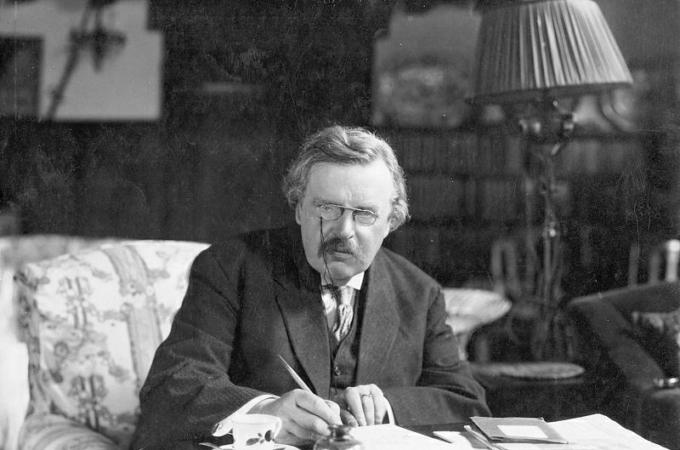

A very similar dynamic obtains in regard to interpreting G.K. Chesterton. His stories, novels, and essays can indeed be read as a nostalgic appreciation of a romantic England gone with the wind, but a close look at the man himself gives the lie to this simplistic hermeneutic. Though he enjoyed life with his wife and friends in his country home in Beaconsfield, Chesterton was at heart a Londoner, a denizen of the pubs of Fleet Street, where he rubbed shoulders with the leading journalists, politicians, and cultural mavens of the time. He loved to laugh and argue with even the bitterest enemies of the religion he held dear. Most famously, over the course of many years, he traveled the country debating with the best-known atheist of the time, his good friend G.B. Shaw, with whom he typically shared a pint after their joint appearances. The point is that Chesterton didn't hide his Catholicism away; he launched it into the wider society like a great ship onto the bounding main.

Paul Tillich was a quiet and serious student of Lutheran theology, preparing for a life as a preacher, when he was called to serve as a chaplain in the German army during World War I. In the course of five years, the young man saw the very worst of the fighting and dying. He said in one of his letters to his wife that it was like witnessing the collapse of an entire world. In the wake of that horrific experience, he sought a new way of articulating the classical Christian faith for the twentieth century, which is to say, for people whose world had fallen apart. He did indeed spend countless hours with his books, hunkering down to learn the great Christian intellectual tradition, but he insisted that the ultimate purpose of the theologian is to go out to meet the culture "mit klingendem Spiel," which means, roughly, "with fife and drum." Like his one-time colleague Karl Barth, who said that Christians ought never to crouch defensively "behind Chinese walls," Tillich felt that believers in Christ ought to meet the culture head-on.

This general attitude is present from the beginning of Christianity. From the moment the Lord gave the great commission--"Go and preach the Gospel to all nations"--his disciples knew that the Christian faith is missionary by its very nature. Though it exhibits contemplative and mystical dimensions, it is, at heart, a faith on the move, one that goes out. How fascinating that the Holy Spirit first fell in the heart of a city, and that the greatest figure of the Apostolic age, Paul of Tarsus, was an urbane fellow, at home on the rough and tumble streets of Antioch, Corinth, Athens, and Rome.

This, by the way, is why I have a particular affection for YouTube, on whose forums I am regularly excoriated and attacked, and Reddit, where secularists, agnostics, and atheists are happy to tell me how stupid I am. Well, why not? Chesterton faced much worse in Fleet Street bars; Paul met violent opposition wherever he went; Frodo and Bilbo looked into the abyss. Good. We Christians don't stay in hobbit holes; we go on adventure, mit klingendem Spiel!

- Bishop Robert Barron is the founder of the global ministry, Word on Fire, and is an Auxiliary Bishop in the Archdiocese of Los Angeles.