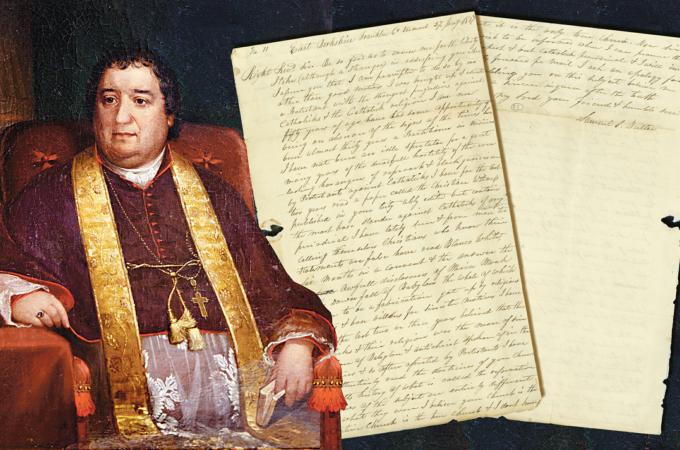

Bishop Fenwick corresponds with an early Catholic convert

In the Bishop Benedict Fenwick Papers reside four letters from a Dr. Samuel Butler of East Berkshire, Vermont, spanning 1837 through 1841. The letters discuss Butler's choice to convert to Catholicism and its impact on his social and professional life.

Butler first writes to Bishop Fenwick in January of 1837, introducing himself as a 50 year old Protestant who for the past 30 years has been practicing medicine. He claims his journey towards Catholicism started several years prior, after reading the Christian Witness, published in Boston, and being appalled not only by the anti-Catholic rhetoric within, but that "men...calling themselves Christians who know their statements are false" would publish such slander. He now believes that the Catholic Church is the true Church, and wishes to be informed, asking the bishop to send him Catholic periodicals so that he may be better informed about Catholic doctrine.

He writes again the following September, apologizing for not being able to see Bishop Fenwick during his recent visit to Burlington, Vermont. Butler wished to ask him in person if he was worthy of joining the Catholic faith but, since that time, has done so, having been baptized by Father Jeremiah O'Callaghan. He also reveals some of the hardships he has faced since converting. While his personal relationships have not suffered, his fellow physicians and patients in neighboring communities have grown suspicious of him, and he asks Bishop Fenwick whether publishing a defense of his decision to convert would ease their fears.

The next letter between Dr. Butler and Bishop Fenwick dates to Aug. 14, 1840. He opens "Dear Sir, I address you as one ordained of God to minister in holy things..." He continues to thank Bishop Fenwick for his advice, leading us to believe that they regularly corresponded in the intervening years. He writes to lament about "the scarcity of good books and periodicals in this section of the country," insisting that whatever people read they believe, and it often instills in them false believes and prejudices -- "The great mass of mankind are so constituted in that peculiar manner that everything is taken for truth that appears in print, it is in this way that the falsehood and calumny against the church of Christ has been circulated and obtained so much footing."

The final letter we have from these exchanges dates to Dec. 1, 1841. Again, the letter seems to indicate that they corresponded regularly. He notes marked improvements in his professional life from when he initially converted to Catholicism, writing that he is "enjoying perhaps as much confidence of the people as my neighboring physicians."

The final letter also alludes to the difficulties of being a convert in a Protestant family and community. He recounts how he discussed his decision with his Protestant minister at the time of conversion, and left on peaceful terms, and so still offers financial assistance to him along with supporting the local Catholic priest. He also still attends services there occasionally, so he can remain connected with the community, but that has brought him into conflict with the local Catholic priest, who refuses him Communion until he stop attending his former church. Butler argues that "it is but for me and even for the Catholic Church that [I] continue my usual friendly intercourse with this people..."

This small detail speaks to an issue of which there are other examples in the early history of the Diocese of Boston. Some priests who originated from Europe and enjoyed a relationship with Protestants were seen as a liability by their superiors, but in the United States this was often seen as an asset. This was due to the Catholic community comprising a small minority of the population, and the ability to foster an understanding with the much larger Protestant community allowed both to peacefully coexist in American cities.

It is believed around 2,000 people converted to Catholicism during Bishop Fenwick's tenure as Bishop of Boston, a significant increase to the small Catholic population prior to the large-scale immigration to come within a decade of these exchanges. A few of these converts would continue to become Catholic priests at a time when they were so desperately needed to serve New England's Catholic population.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.