He rose again from the dead

I want to change how you think about the Resurrection by asking you to imagine it in a new way. You need to use your imagination, not in the sense of thinking of some fable which never existed, but in the sense of grasping more accurately what did -- and does -- exist.

Christianity is necessarily concrete. "Our salvation hinges on the flesh," ("caro salutis est cardo"), Tertullian said. We must use the imagination to grasp whatever is concrete. "That which we have seen and have heard, we declare unto you," (1 Jn 1:3). A purely conceptual grasp of these matters will be at least incomplete.

I assume you approach this question of the resurrected body of Christ, as did I, with images of a gloriously triumphant Lord, perhaps floating in air in front of a cross.

You may also have in your mind images derived from false philosophy, not Christianity -- of the soul as a kind of luminous spirit, liberated from the body upon death, rising upwards towards heaven. "Heaven has gained another angel," as people will say, who hold this heresy in a common form.

In fact it's not easy to make sense of the Resurrection on such a view. Why should the luminous liberated spirit return to the body after all? That was specifically why the early Christians added to their credo, "I believe in the resurrection of the body."

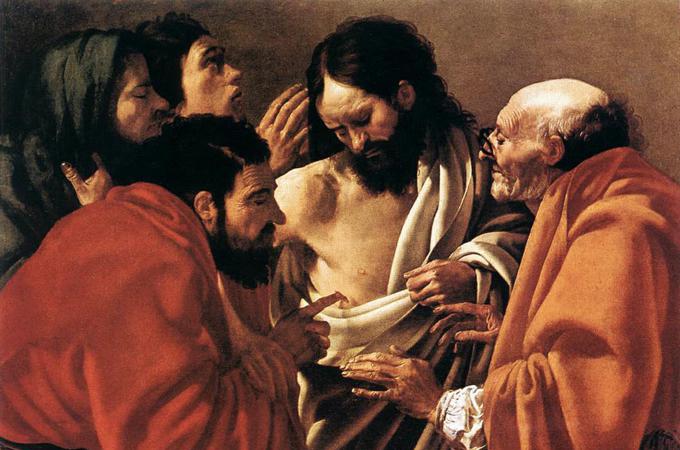

In imagination, the necessary correction to this view involves two steps. The first is to imagine the resurrected body of Christ as still bearing the wounds of the Passion.

It's interesting that, although we say that Thomas doubted, nonetheless he was at least fully convinced in advance that, if Jesus were resurrected at all, his body would show wounds, "Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the place of the nails, and put my hand into his side, I will not believe" (Jn. 20:25). Evidently, he had been well instructed by the Master, whose flesh precisely was at stake.

The recent 3-D reconstruction of the Shroud of Turin imputes 370 wounds to the front of Christ and by inference at least an equal number on the back. Did the resurrected Lord display all of those wounds as well, and the broken nose and dislocated shoulder? The saints say no. They say, first of all, that it was a matter of free choice that Our Lord would show wounds at all. "He might, had He pleased," says St. Augustine, "have wiped all spot and trace of wound from His glorified body; but He had reasons for retaining them."

But then wounds would be retained in the body only in such a way as to display virtue: "We are, as I know not how," St. Augustine adds, "afflicted with such love for the blessed martyrs, that we would wish in that kingdom to see on their bodies the marks of those wounds which they have borne for Christ's sake. And perhaps we shall see them; for they will not have deformity, but dignity, and, though on the body, shine forth not with bodily, but with spiritual beauty. ... For though all the blemishes of the body shall then be no more, yet the evidences of virtue are not to be called blemishes."

The resurrected body of the Lord, then, retains "evidences of virtue." It is not human life and suffering in general, but this life and this passion, that it displays.

While dwelling on this point, let us also consider that the body would show his origin: it is unmistakably the Semitic body of a son of David, and resemblance to his mother -- you can see her in him -- would give reflected evidence, too, of her virtue. (See for example "The Small Cowper Madonna" of Raphael, where the two faces are as if mirror reflections.) He is Jesus the Nazorean.

But the second step is to imagine the resurrected Lord as having returned from the dead. In my experience, Christians do not reflect on this point. And yet the Catechism points out that it is a separate assertion of the creed: "The frequent New Testament affirmations that Jesus was 'raised from the dead' presuppose that the crucified one sojourned in the realm of the dead prior to his resurrection" (n. 632).

Did the soul of Lazarus also sojourn among the dead before he was raised? There seem to be verifiable cases of "near death experiences," where persons on the point of death, and apparently comatose, nonetheless experience themselves as separated from the body. They give reports of what happened to them, that they could not otherwise have known. Such persons have clearly not "sojourned among the dead." Was the soul of Larazus, then, in contrast, in such a condition, a kind of "natural" separation from the body, yet still somehow "asleep" -- as indeed the Lord described him?

To rise, and to rise from the dead, are different. We would experience a sense of eeriness and natural fear at someone who had risen from the dead. And so the disciples did. When Jesus appeared among them, despite his saying, "Peace be with you!" they were distraught, terrified, filled with fear. Dwell upon this. He is a spirit from among the dead, they think. To conquer this fear, "he showed them his hands and feet" (Lk. 24:40). The one imagination instructs the other.

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.