Images of Mary

Q. I am wondering how the common representation of Mary in art form came to be. Whether in Nativity scenes, statues or paintings, she is usually shown as being Caucasian (or at least European), with a pale complexion and hair that is almost blond. Shouldn't she be depicted instead as dark-skinned, dark-haired and Jewish? (Corydon, Indiana)

A. For many centuries, the focal point of Christianity was Europe, and a heavy majority of the world's Catholics lived on that continent. (In more recent years that has changed rapidly; according to the Pew Research Center, in the year 1910, 65 percent of all Catholics lived in Europe, but by 2010 only 24 percent did.)

Because most religious artists were European, it is not surprising that they portrayed Mary as looking like the people they knew; they were not trying to create a photographic replica of Mary of Nazareth but to appeal to the religious sensibilities of those most likely to view their work.

Had they wanted instead an exact likeness, they would have known even in the Middle Ages that Palestinian Jews at the time of Christ had darker skin, with darker eyes and a dark hair color. (What they might not have known then -- but what nearly all biblical scholars believe today -- is that, based on Jewish marriage customs of the time, Mary was most likely 14 or 15 years old when she gave birth to Jesus.)

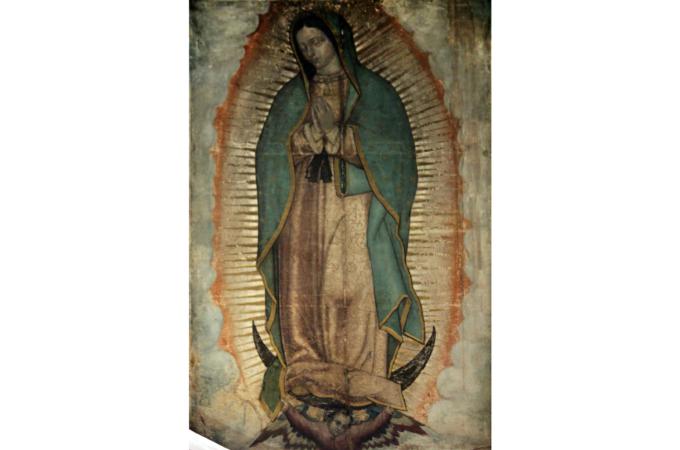

There is, of course, a range of artistic works that do portray Mary with non-European features. Probably the best known of these is the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.

In 1531, Mary appeared to an indigenous named Juan Diego on a hill outside Mexico City. When the local bishop was skeptical and asked for a sign, Mary directed Juan Diego to collect roses in his cloak and bring them to the bishop. As he unfolded the cloak, dozens of roses fell to the floor and revealed the image of Mary imprinted on the inside -- with the dark skin of the indigenous people.

Q. My 23-year-old daughter has recently gotten engaged to a very nice young man. Our family had been planning the wedding, but I began to notice some reluctance on my daughter's part. After a frank discussion, she admitted that neither she nor her fiance have any wish to be married in the Catholic Church.

Both of them have issues with the church, particularly with regard to gay marriage. This is breaking my heart and upsetting my husband as well. I cannot find any clear answer on whether we are allowed to attend her wedding next year; the articles I have seen from religious sources seem to differ in the guidelines they offer.

Can you tell me what I should do? (I don't want to commit a mortal sin but she is my daughter, and I've always told her I would love and support her no matter what mistakes she made.) (Suffolk, Virginia)

A. The first thing I would want is to have your daughter and her fiance talk with an understanding priest over their concerns with some of the church's teachings. He might be able to help them sort out whether their issues are fundamental enough to forgo the strength of the sacraments and the comfort they may once have felt with the church's prayers and practice.

If that suggestion doesn't work and they still decide to marry outside the church, I believe you should feel free to attend the wedding. No doubt, you and your husband have made clear to your daughter your own feelings: the joy and security you experience from the Catholic faith and your hope to pass that on to your daughter as a lifelong gift.

As you said, she is your daughter, the child of your love. Not to attend the wedding, in my view, risks a permanent rupture and could eliminate any chance of her returning to Catholic practice through your gentle example.

- - -

Questions may be sent to Father Kenneth Doyle at askfatherdoyle@gmail.com and 30 Columbia Circle Dr., Albany, New York 12203.

- Father Kenneth Doyle is a columnist for Catholic News Service