On the value of biblical Hebrew

The Little Flower, St. Therese of Lisieux, wrote in her autobiography: "In Heaven only shall we be in possession of the clear truth. On earth, even in matters of Holy Scripture, our vision is dim. It distresses me to see the differences in its translations, and had I been a Priest I would have learned Hebrew, so as to read the Word of God as He deigned to utter it in human speech."

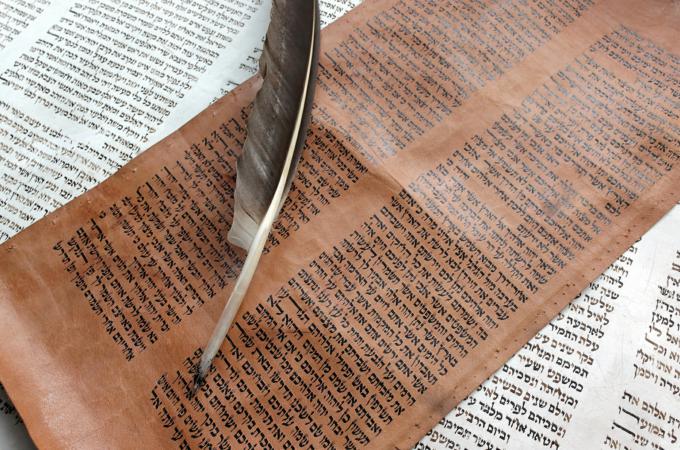

Other saints did learn Hebrew. St. John Fisher, whose martyrdom and feast we celebrated this month, undertook the study of Hebrew at an advanced age. St. Jerome, of course, the author of the Latin Vulgate, the official translation of the Catholic Church for centuries, learned Hebrew from a rabbi in the Holy Land, to be able to translate from the original Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, rather than simply from the ancient Greek translation called the Septuagint.

Now we Americans are generally not very good at or even interested in other languages than English, if we're interested in that. And when it comes to classical languages like biblical Hebrew, ancient Greek, or largely defunct Latin, that lack of interest is heightened by the common perception that these languages are largely dead, and that knowing them is both difficult and not very useful, practically speaking. Obviously, though, knowledge of the Bible in the original languages, Hebrew for the Old Testament, and Greek for the New, is important from a scholarly perspective.

While not everyone has to have a scholarly mastery of the Bible, a basic familiarity with God's Word is vitally important for every believer. The Bible spells out the rules for Christian living, most notably in the Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes. And since Christianity arose from Judaism, as the New Testament is rooted in the Old (indeed Jesus prayed the Psalms in Hebrew), an ability to relate to the Hebrew text is invaluable for theologians, priests, and educated laypeople.

St. Jerome wrote of the "Hebraica veritas," the true meaning of the Hebrew, as the preferred approach to biblical interpretation of the Old Testament. Obviously, since the New Testament was written in Hellenistic (Koine) Greek, knowledge of that language is also essential for Christian biblical scholarship. While there are many good translations of the Bible into English, nothing can really substitute knowledge of the original languages.

As the Venerable Pius XII wrote in an encyclical on biblical studies in 1943: "Not only the Greek language, which since the humanistic renaissance has been, as it were, restored to new life, is familiar to almost all students of antiquity and letters, but the knowledge of Hebrew also and of their oriental languages has spread far and wide among literary people. Moreover there are now such abundant aids to the study of these languages that the biblical scholar, who by neglecting them would deprive himself of access to the original texts, could in no way escape the stigma of levity and sloth. For it is the duty of the exegete to lay hold, so to speak, with the greatest care and reverence of the very least expressions which, under the inspiration of the Divine Spirit, have flowed from the pen of the sacred writer, so as to arrive at a deeper and fuller knowledge of his meaning."

Our love for Jesus Christ, his Church, and the origins of Christianity in Judaism, should also find expression in a desire to visit the Holy Land before we die. Just as the observant Muslim wants to make a pilgrimage to Mecca, Christians should want to visit the places in Israel associated with our Lord's life: Bethlehem, Nazareth, Galilee, and, of course Jerusalem, the site of Jesus' Passion, Death and Resurrection. While visiting Rome "videre Petrum," to see Peter in the person of the pope, and see St. Peter's Basilica and the Sistine Chapel, should obviously be on the bucket list of Roman Catholics, so too should the Holy Land and Israel.

- Dwight G. Duncan is professor at UMass School of Law Dartmouth. He holds degrees in both civil and canon law.