Calling God our Father

Our last 11 grandchildren in a row have been girls, so I've gotten careful about asserting claims of male prerogative. But this Father's Day got me thinking about how we talk to God. Pope Francis recently reminded us, in one of his general audiences, that "when the disciples asked Jesus to teach them to pray, he taught them to call God Our Father."

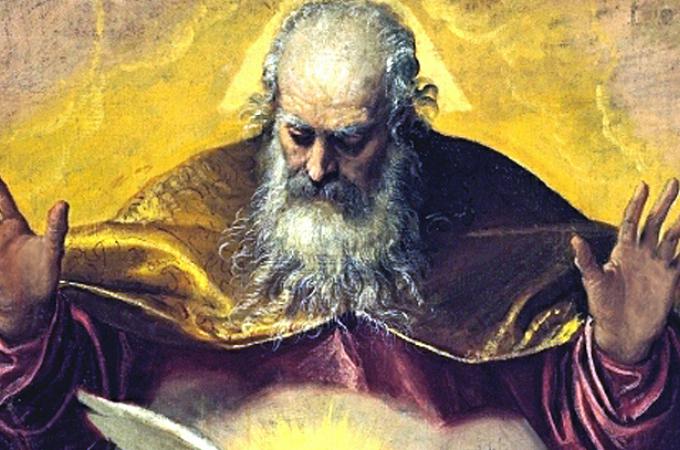

And so we do. We say the Our Father in our morning and evening prayers, in the Communion rite at Mass, six times in the rosary. But how do we square this with another truth we all acknowledge? We are made in God's image, not he in ours. God, the Catechism of the Catholic Church says, "is neither man nor woman. God is pure spirit in which there is no place for the difference between the sexes."

Reconciling these two thoughts, Pope Francis says, is "the great religious revolution introduced by Christianity" -- the idea that we could "dare to speak to the transcendent and all-holy God as children speak, with complete trust, to a loving father."

The pope is fond of invoking the parable of the prodigal son (he prefers to call it the parable of the merciful father) as a metaphor for the Christian life. The father teaches his sons the way they should live. He gives them freedom to spend their inheritance as they choose. And he is always ready to forgive; he runs out to meet the repentant sinner while he is still a long way off.

This way of understanding "the fatherhood of God," Pope Francis says, is the source of Christian hope. Because God is like this, we dare to hope for eternal life.

These days, though, talking this way about God is unsettling to the progressive mind. At some parishes, we will say "for the praise and glory of God's name" rather than "for the praise and glory of his name" during the preparation of the gifts.

Duke Divinity School's course of studies offers guidelines for inclusive language that suggest using "God" and "Godself" "as substitutes for he/she and him-/herself." And if we want to talk about God's personal relationship with us, there are nongendered options like "God is parent to us all."

These revisions sound odd and clumsy (Godself? Really?), and for me that's a sufficient reason for resisting them. But I also suspect that they are put forward for reasons very different from those the catechism has in mind when it says that with God "there is no place for the difference between the sexes."

I think that the concern about using male pronouns and praying the Our Father is that it seems unfair to women, not that it's offensive to God. The business of praying has gotten tangled up with Title VII and Title IX and the Equal Pay Act; with the role of women in the workplace; and with the assignment of domestic responsibilities for child rearing.

These days the preference for inclusive language may also find support in the movement for freedom of choice about gender expression and identity. But that's also about us, not about him.

It is a mistake to let sexual politics creep into our prayer life. Jesus told his disciples to call God Our Father. He had his reasons, and they are better than ours. That ought to be the first principle.

We need to embrace this way of talking to him, because it is the source of our hope as Christians. Like a father, God loves and teaches his children. He sets them free. And he stands at the door of our home, always ready to show mercy.

- Garvey is president of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.