Boston's first Catholic school

Jan. 29 through Feb. 4 is National Catholic Schools Week, which has been observed starting on the last Sunday of January since its inception in 1974. This year's theme is "Catholic Schools: Communities of Faith, Knowledge and Service."

With that in mind, we look to the earliest days of Catholic education in the Archdiocese of Boston. The first classes known to have been offered were to girls only, and were held by the Sisters of Charity in the basement of the Cathedral of the Holy Cross on Franklin Street. But the first institution appears to have been a female academy operated by the Ursuline Nuns who arrived in 1820 at the invitation of Bishop John Cheverus, who had built a convent and school next to the cathedral for that purpose.

The school accepted about 100 students, half of whom attended school during the morning hours, and the other half in the afternoon. Since many in attendance were the daughters of poor immigrants, they paid no tuition, the operating costs being covered by inheritances from Fathers John Thayer and Francis Matignon, who shared the vision of such an institution being established in Boston.

Following Bishop Cheverus' departure in 1823, many of the sisters who founded the school fell victim to tuberculosis. With many of the founding nuns having succumbed to illness, new leadership was found in the form of Madame Saint George, known before her vows as Mary Anne Moffatt. She allied herself with Bishop Benedict Joseph Fenwick, Bishop Cheverus' successor, who believed the illness was due to being too confined in the city, and looked to move the convent and school elsehwere.

In 1826, with proceeds from the sale of the Boston site, 10 acres were purchased in Charlestown for the new convent and academy. Bishop Fenwick immediately set himself to work overseeing improvements. A farmhouse which stood on the ground was expanded to include a kitchen and chapel. He also constructed a fence so the Ursulines would remain cloistered, dug a well, and built a new road. He also landscaped the grounds, which expanded to a total of 24 acres via subsequent purchases over the next several years.

This new school, named Mount Benedict in honor of Bishop Fenwick, would in some ways be starkly different to its predecessor. This school, with its secluded lifestyle and extensive curriculum, attracted the daughters of upper-class families, often Unitarians, who were "willing to send their daughters great distances, to be separated from them for long periods, and to put aside their religious prejudices knowing the girls would return home fully prepared to take their place in the society in which they were to move." Formerly tuition-free, attendance now came at the cost of $160 (the equivalent of about $4,000 in 2017) per year.

In early 1828, Bishop Fenwick began to advertise for boarders, and by the early 1830s the school appeared to be thriving, with 50 to 60 boarders per year. Students typically rose between 5 a.m. and 6 a.m. and attended morning prayer which was read aloud, followed by 30 minutes of silence. Next, students took a breakfast of bread, butter, and milk, before three-and-a-half hours of class. They would break around 11 a.m. for lunch, recess, or other activities, before returning to the classroom for an afternoon session until 5 p.m. The day concluded with afternoon tea, followed by free time and an evening prayer.

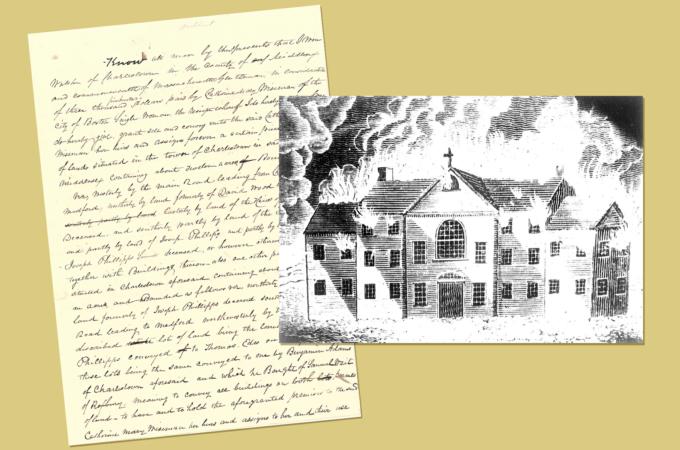

Unfortunately, this beacon of Catholic girls' education was to be short-lived but, unlike many institutions of its kind, not due to a lack of financial support or mismanagement. On Aug. 11, 1834, in an infamous and well-documented incident, an anti-Catholic mob appeared outside the convent, scattering its inhabitants and burning the structures on the property. The convent and school were never rebuilt.

For Further Reading see: Nancy Lusignan Schultz, "Fire and Roses: The Burning of the Charlestown Convent, 1834."

THOMAS LESTER IS THE ARCHIVIST OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.