Civil war chaplains

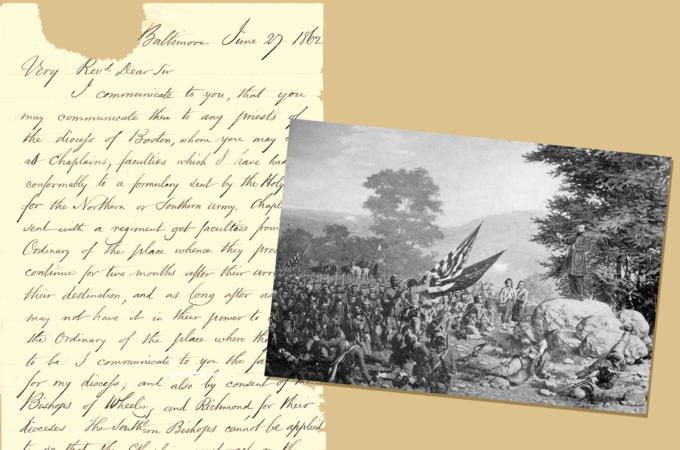

A letter from Archbishop Francis Patrick Kenrick of the Archdiocese of Baltimore to Archbishop John Joseph Williams of the Diocese of Boston, dated June 27, 1862, discusses faculties, or the authority granted to priests, serving as military chaplains during the American Civil War.

The war formally started in April 1861, when artillery batteries ringing Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, opened fire on Fort Sumter and its United States Army garrison. The garrison had maintained its post despite warnings from state officials, who were repossessing all forts in the state with loyal militia following their decision to secede from the Union the previous December.

The United States at this point in history possessed a very small professional army, so with the outset of the conflict, both the United and Confederate States governments scrambled to assemble volunteer armies on an unprecedented scale in this country. Included in these ranks of new recruits were military chaplains who would accompany the soldiers in the field, providing for their spiritual needs and, no doubt, helping them cope with the horrors they would witness over the next four years.

We can only guess what Archbishop Kenrick felt at the time of writing this. Having served as the Archbishop of Baltimore since August 1851, a city which was geographically nestled between free and slave states, he would have witnessed first-hand the arguments and actions of both sides.

Whatever his personal feelings, in his letter he gives Bishop Williams permission to grant additional faculties to priests who will be leaving dioceses to serve as military chaplains -- both for the northern and southern armies. In light of the conflict and subsequent mobilization, he references a list of these faculties from the Holy See that can be specifically granted to those individuals.

When faculties are granted, an ecclesiastical superior, such as a bishop, is extending his power to the priest receiving it. For instance, a bishop is required to administer the sacrament of Confirmation; however, if a priest is granted the appropriate faculty by his bishop then he may do so legally in the eyes of the Church. Other powers may include the ability to grant permission to skip fasting days, grant marriage dispensations, etc.

Archbishop Kenrick continues that, in these circumstances, the faculties will "continue for two months after their arrival at their destination, and as long after as they may not have it in their power to apply to the Ordinary of the place where they happen to be."

While there are several pieces of his correspondence from this time, Archbishop Kenrick would not live to see the end of the war, serving as archbishop until his death on July 8, 1863. Archbishop Williams himself was not actually a bishop at the time the letter was written, and only named so after the war, in January 1866. Shortly before the letter was written, he became an administrator of the Diocese of Boston, and is known to have taken on much of the responsibility for the diocese while his predecessor, Bishop John Bernard Fitzpatrick, sought a cure for his physical ailments abroad. Williams would go on, as his title implies, to be Boston's first archbishop when it was elevated to an archdiocese in 1875.

THOMAS LESTER IS THE ARCHIVIST OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF BOSTON.