Cardinal Cushing, advocate of equality for all

May 18th marks the 120th anniversary of the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling in the United State Supreme Court. This infamous ruling gave validity to the idea of "separate but equal," perpetuating racial segregation in the United States for several more decades.

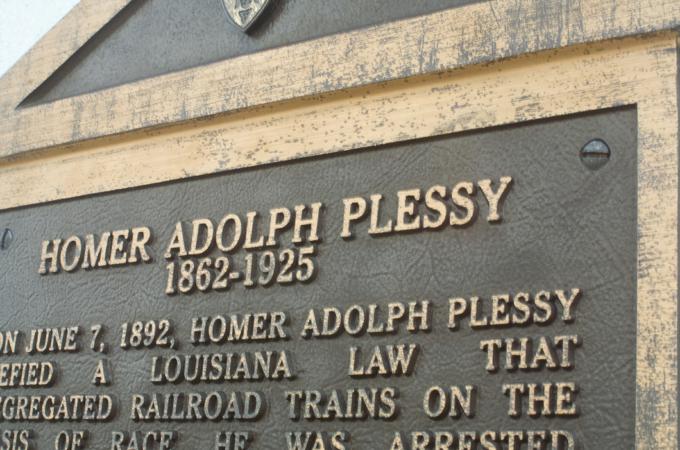

It began on June 7, 1893, when 30-year-old Homer Plessy was imprisoned for sitting in a "White" train car of the East Louisiana Railroad. His arrest was legal under the Separate Car Act of 1892, passed by the Louisiana State Legislature, and requiring him to travel in a "Colored" car.

He challenged this state law, and the case eventually reached the United States Supreme Court. Plessy's defense was based upon the 13th and 14th Amendments of the United States Constitution. The 13th, passed immediately after the Civil War, abolished slavery, while the 14th guaranteed citizens equal protection under the law. A 7-1 majority ruled in favor of the state law, the lone dissenter being Justice John Harlan.

The "separate but equal" decision stood for 58 years, until May 17, 1954, when a ruling was made in another Supreme Court case -- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Kansas). In this instance, the Supreme Court justices voted unanimously in favor of the parents of Linda Brown, an eight-year-old student who was prohibited from attending the "White" school in her neighborhood. After revealing the decision, Chief Justice Earl Warren commented upon the detrimental effects of segregated schools, and stated that "in the field of public education, the doctrine of 'separate but equal' has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal."

The papers of Cardinal Richard J. Cushing, held by the Archdiocesan Archive, contain several documents addressing these issues, in which he advocates for equality in the eyes of the law, and in the eyes of each other.

In a document that dates to the 1950s, he acknowledges one of the harsh truths in our nation's history, writing that "historians will have their problems explaining why a century was allowed to elapse between the time 'the slaves were freed' and the true liberation of the Negro began to be accomplished. It would be interesting to catalogue the long list of excuses which otherwise fair and freedom-loving Americans allowed themselves in this context in order to explain inaction, postponement, and an undisturbed conscience."

He continues that simply identifying and acknowledging these past inadequacies is not sufficient, but that action must be taken to ensure that each and every citizen is guaranteed his or her civil rights. To do so, he writes, "we must rediscover an authentic love for our fellow man...Without this basic spiritual ingredient, no formula can possibly resolve our problem; with it our every effort will be blessed by God Who is the Father of all men without exception."

While the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling and the "separate but equal" doctrine contribute to the "sad stain which spreads across the fabric of America," as Cushing described it, it is important to remember these events, decisions, and attitudes, lest they be repeated. While Cardinal Cushing's words directly reflect the time in which he lived, they remain relevant today, and are worth our attention as we continue to try and improve as a society, as Catholics, and as human beings.

For further reading:

Cardinal Richard J. Cushing Papers. Archive, Archdiocese of Boston.

Plessy v. Ferguson: www.pbs.org/wnet/jimcrow/index.html.

United States Constitution: www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution.html.