The pope and magnanimity

An old attack on Christianity says that because Christians are supposed to be humble, they cannot in principle strive to be great. Christianity is therefore incompatible with the admirable cultures of Greece and Rome, where greatness of character or "magnanimity" was highly praised.

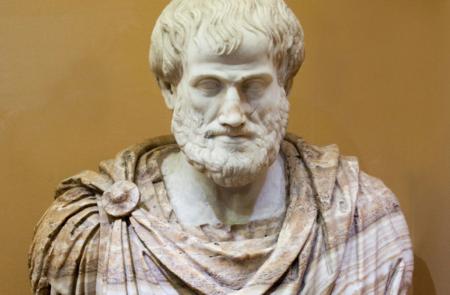

Bertrand Russell is always a good source for attacks on Christianity, and in this matter too he states the point best: "The best individual, as conceived by Aristotle, is a very different person from the Christian saint. He should have proper pride, and not underestimate his own merits." There is an irreconcilable difference between pagan and Christian ethics, Russells says, and "Nietzsche was justified in regarding Christianity as a slave-morality." The nub of the matter is that "Christian ethics disapproves of pride, which Aristotle thinks a virtue, and praises humility, which he thinks a vice."

One may concede that there is an appearance of a difficulty. Aristotle teaches that a virtuous person should be aware of his own virtue and then claim the honor rightly due to him as virtuous. On the other hand, consider the widely-esteemed Litany of Humility of Cardinal Merry del Val: "O Jesus! Meek and humble of heart, Hear me. From the desire of being esteemed..., From the desire of being honored ..., Deliver me, Jesus! That others may be chosen and I set aside ...,That others may be praised and I unnoticed ..., Jesus grant me the grace to desire it!"

So how do we, as Christians today, deal with this difficulty? Do we embrace humility and say "so much the worse for pagan ethics," or do we deny the contradiction and insist that Christianity never rejected the culture of Greece and Rome but claimed and saved the best within it?

Bertrand Russell wrote at the end of the Victorian era, when a bourgeois Christianity was the norm. Hence anyone could claim to tell us what "Christian ethics" says -- apparently even an atheist such as Russell. Moreover, the charge that Christianity rejected any ideal of human greatness could seem plausible, since so many ordinary persons were Christian and few of them appeared to be "great." However, today Christian belief is a minority phenomenon, at least culturally speaking, and we are all aware that one cannot speak of what "Christianity" says.

So if one is puzzled over this question, one must decide it by appeal to the proper authorities. I can think of two: St. Thomas Aquinas and the pope.

As it happens, and not surprisingly, St. Thomas in his "Summa" considers the very difficulty that Bertrand Russell raises: "No virtue is opposed to another virtue. But magnanimity is opposed to humility, since 'the magnanimous deems himself worthy of great things, and despises others,' according to Aristotle's 'Ethics'" iv, 3. Therefore magnanimity is not a "virtue." The Angelic Doctor answers that "magnanimity and humility are not contrary to one another, although they seem to tend in contrary directions, because they proceed according to different considerations." "There is in man something great which he possesses through the gift of God; and something defective which accrues to him through the weakness of nature ... magnanimity makes a man deem himself worthy of great things in consideration of the gifts he holds from God ... humility makes a man think little of himself in consideration of his own deficiency."

St. Thomas's treatment is marvelous and balanced, and one is reminded of G.K. Chesterton's claim, that Christianity seems a paradox to the world, because it manages to harmonize opposites which, when found separate in the world, become grotesque and distorted.

Our other authority is the pope. Now it turns out that one of the very best statements of Christian magnanimity is a spontaneous address by Pope Francis "to the Students of the Jesuit Schools of Italy and Albania" in June 2013. The pope told these students that the main thing they should learn while at school is how to be magnanimous. "What does being magnanimous mean? It means having a great heart, having greatness of mind; it means having great ideals, the wish to do great things to respond to what God asks of us. Hence also, for this very reason, to do well the routine things of every day and all the daily actions, tasks, meetings with people; doing the little everyday things with a great heart open to God and to others. It is therefore important to cultivate human formation with a view to magnanimity."

The Holy Father continued, "In order to be magnanimous with inner freedom and a spirit of service, spiritual formation is necessary. Dear young people, love Jesus Christ more and more!" He then turned to the teachers: "Give them hope and optimism for their journey in the world. Teach them to see the beauty and goodness of creation and of man who always retains the Creator's hallmark. But above all with your life be witnesses of what you communicate."--There seems here an interesting anticipation of the themes of "Laudato Si": when we view the beauty and goodness of creation, we should be inspired to widen our horizons beyond the small-mindedness of the "throwaway culture." Could magnanimity, then, actually be the hermeneutic key to "Laudato Si"?

Do something great with your life. Be a co-redeemer with Christ. Through faith contribute to God's narrative. Pope Francis's spontaneous remarks show us that striving for greatness is not something pasted onto Christian life but of its very heart and essence.

MICHAEL PAKALUK IS PROFESSOR AND CHAIR OF PHILOSOPHY AT AVE MARIA UNIVERSITY.

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.