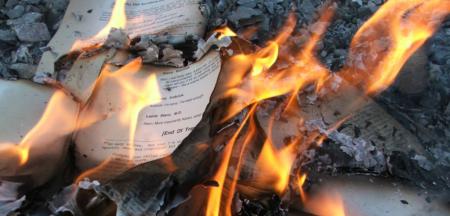

The new way of burning books

We learned in history class that when Gutenberg invented moveable type, and books could readily be copied, so that anyone could own one, what it meant to live a human life also changed. The arrival of the Era of the Book meant, for instance, the decline of local communities with their oral traditions, and the weakening of authorities in learning, who had custody over libraries.

The ramifications for Christianity too were enormous. Protestantism was simply an impossible viewpoint before Gutenberg. If only established communities such as schools or monasteries could realistically own books, then the idea that individuals are meant to make up their minds on their own about matters of faith, through an unmediated study of the printed text of Scripture, looks not simply wrongheaded but also impracticable and absurd.

It would have been interesting to be alive during that transition, actually seeing the book replace orality. Would we have been clearheaded enough to see the change and to embrace what was good, while not giving in to distortions -- without, in gleefully welcoming the book, throwing out what beforehand had been specifically good about human life?

But an equivalent change is taking place now. Do we see it? The Era of the Book has lapsed. Books are no more. They have been replaced by laptops, tablets, phones, and now watches. Books will continue to exist, if they do, only as a result of a definite choice in their favor. The flow is going completely in the opposite direction. And what difference will it make for the faith? How should we react?

Please observe that a text on a glowing screen is not a book any more than a speech written down is a speech. Nor is it enough to say, with Marshall McLuhan (who liked a good pun), that "the medium is the massage"-- since the issue is not that of a choice among modes of delivery but rather a change in our form of life.

How do we start to think about all this? One might begin with the inverse Golden Rule ("do unto yourself, as you do unto others") and point out what is obvious in the raising of children. From there one can begin to reach conclusions about how to order our own lives.

This much seems clear: There are certain goods which one gets from reading books, but not easily or at all from time spent with screens. It follows that households should make a definite effort to create a "culture of books" in the home, say, for example, by spending time several evenings each week reading books together, with the screens turned off.

What are those goods which children get only or most easily from books? As there are many, let us enumerate: (1) The exercise of the imagination, since vivid images on screens drive the imagination out. The imagination is as much a power of the human soul as thought and feeling, and children in whom it withers grow up into "men without chests." (2) Concentration, since exactly what draws us to a glowing screen makes us want to see quickly a change in that glowing screen. (3) A soothing of the senses, since the constant glow of the screen is a constant (over-) stimulation of our sense periphery.

There is the interesting question of what type and level of stimulation we are "meant" to experience habitually in ordinary life. Not that of a bombing raid for instance. Arguably not the noise and light of a modern city. Take simply a mechanical mouse and set it down among a group of indigenous people in the Amazon basin and maybe (as in Waugh's "Handful of Dust"), from the inherent strangeness of the experience, they will spontaneously run away and not wish to come back for hours. But if a smart phone had been placed before them, turned on to its startup screen, just perhaps they would have stood and watched it transfixed until the battery died out. We might not implausibly outfit a "man in the state of nature" with a book, but not with a smart phone.

One can add: (4) Freedom of judgment, because a reader is more free to separate himself from his book and formulate a judgment about what is claimed; also (5) independence of judgment, since a reader is in the presence of the author of the book, but typically someone looking at a screen is aware that the very thing he is dealing with is being looked at also by thousands or millions of others -- creating a "crowd" effect which is hard to dislodge.

Books also imply (6) a sharper memory, since memory is aided through associations with place, and practiced readers know exactly where on a page some text may be found, whereas e-pages vary with screen size and in any case "flow." There is moreover (7) a selflessness fostered by reading -- think of how you "lived" in someone else's life (not even real!) the last time to read a great novel. The association of screen-presence with narcissism, in contrast, is a truism.

How the Demise of the Book will affect the faith is a topic for another time. But note finally (8) the contemplative character of reading, and its closeness to prayer, in evidence of which: the category of "spiritual viewing" is yet to be devised; and no one finds it irrational that missals in church are still printed.

MICHAEL PAKALUK, PROFESSOR AND CHAIR OF PHILOSOPHY AT AVE MARIA UNIVERSITY, IS A MEMBER OF THE PONTIFICAL ACADEMY OF ST. THOMAS AQUINAS.

- Michael Pakaluk is Professor of Ethics and Social Philosophy in the Busch School of Business at The Catholic University of America. His book on the gospel of Mark, ‘‘The Memoirs of St. Peter,’’ is available from Regnery Gateway.