The responsibility of ecological stewardship

Not long after St. John XXIII's social encyclical Mater et Magistra made its appearance in 1961, a wisecrack began making the rounds among Catholics who'd taken umbrage: "Mater, si; magistra, no"--mother, yes; teacher, no. In other words, the Church has a maternal relationship with her members but is not their teacher on matters of an economic, political, and social nature.

While this was what passed for cleverness back then, the cleverness, such as it was, was of a highly destructive variety. Among other things, "Mater, si; magistra, no" helped set the stage for the self-righteous dismissals that greeted publication in 1968 of Pope Paul VI's encyclical Humanae Vitae reaffirming the Church's condemnation of contraception.

Just as the smart-aleck rejection of Mater et Magistra amounted to telling the Church to stay out of the arena of social justice, so this response to Humanae Vitae meant the Church should stay out of the bedroom--a tasteful turn of speech time and again employed by some of the encyclical's more raucous critics.

As time went by, knee-jerk antipathy to Church teaching spread to other areas where dissenters happened not to like what was taught. Now it appears we may be facing a new eruption recalling these earlier events. With publication of Pope Francis' long-awaited encyclical on the environment apparently imminent, the chorus of dissent is tuning up again. No papal document in years has received so much prejudicial negative comment before it's been read.

A typical remark by a good Catholic man: "With all the problems we have now, why does the Pope need to talk about climate change?" To which the obvious answer is: When the time comes, read the encyclical and maybe you'll find out.

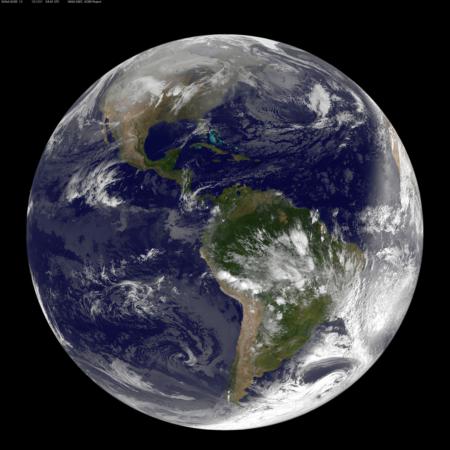

In this day and age it should hardly need saying that whether and how humankind rises to the challenge of environmental stewardship are questions carrying serious moral weight. That's not to say every suggested solution to every environmental problem is necessarily correct. But in matters of ecological morality, Pope Francis has more right than most to be heard. That includes being heard on global warming.

This isn't the first time a pope has written about ecology. Several recent popes have done that. Consider the passages on the human duty to safeguard the environment in St. John Paul II's great prolife encyclical of 1995 Evangelium Vitae.

The responsibility of ecological stewardship exists, John Paul said, "not only for the present, but also for future generations." Then, quoting an earlier encyclical of his, he added: "The dominion granted to man by the Creator is not an absolute power...to dispose of things as one pleases....When it comes to the natural world, we are subject not only to biological laws but also to moral ones, which cannot be violated with impunity" (Evangelium Vitae, 42).

There's plenty more, here and elsewhere in the writings of John Paul II and other pontiffs, but this much at least should be clear: When Francis speaks on the environment, he won't be speaking in a vacuum but will be adding his voice to in a growing tradition of ecological teaching by the papal magisterium.

Despite that, though, some Catholics--"emboldened by the internet," as one writer recently put it--already have taken to the blogs to express their epithet-laden displeasure or do some simple name-calling about what they imagine the Pope will say. Here is a symptom of a pre-existing spirit of pathological contentiousness that threatens to escalate once the new encyclical comes out. This calls for penance and prayer.

- Russell Shaw is the author of more than twenty books. He is a consultor of the Pontifical Council for Social Communications and served as communications director for the U.S. Bishops.