The Plan of Life

Pope Francis has stressed that the 14-month Year for Consecrated Life that he inaugurated on the first Sunday of Advent is not meant to be solely for religious brothers, sisters and priests, for consecrated virgins, widows and hermits, and for members of secular institutes and societies of apostolic life. It's meant to be lived as a "grace" by the entire Church, including the vast majority of the Church that is comprised of the laity.

There's much that all Catholics can learn from those in consecrated life to live out the Christian life better. Consecrated men and women teach all of us about the meaning of baptismal consecration, the nature of vocation, the precedence of God's kingdom, the priority and practice of prayer, the importance of community life, the continuance of Christ's mission of charity, and the true wealth, love and freedom that comes through closer assimilation of Christ's poverty, chastity and obedience.

But I think perhaps the most important thing of all that consecrated men and women teach the entire Church is about the pursuit of Christian perfection and the paths that lead to it.

It's been now fifty years since the Second Vatican Council stressed the "universal call to holiness," that "all Christians in any state or walk of life are called to the fullness of Christian life and the perfection of charity" (LG 40). But we have to admit that, at a practical level, even though the Church in most places has done a good job in teaching that all are called to be saints, the Church has generally been doing a very poor job in training to people to be saints.

Over the last half century the faith life of the average Catholic in the United States has gotten worse, not better. Mass attendance has gone way down, not up. Catholic Biblical and catechetical illiteracy has worsened. More Catholic parishes and schools are closing than being built and thriving. Catholics are still sinning, but most aren't repenting and confessing their sins. Rather than pursuing perfection, Catholics can sometimes think that on the bell curve of Catholic practice if they're just doing the minimum they're already in the upper echelons of fidelity.

That's one of the reasons why the Year for Consecrated Life is so important. Consecrated men and women are palpable reminders that God calls us to holiness, not mediocrity.

Prior to the Second Vatican Council, there was the commonly accepted caricature of Christian faith that if one wished to become a saint, one needed to become a priest or religious. Priests and religious were the ones who sought the A's in the gift of Christian life, the idea went, whereas everyone else was on the pass/fail track with an almost guaranteed enrollment in post mortem purgatorial reform school.

One of the reasons why this idea was popular was because of the discipline found in consecrated life. Novitiates, seminaries and religious communities were spiritual boot camps where no defect was left uncorrected. High expectations were given along with a thorough formation in the spiritual life to help meet those expectations.

One of the most important fruits the Church as a whole could take from this Year for Consecrated Life is the importance of this thorough spiritual training if people are to come to the fullness of Christian life and the perfection of love. Without adequate formation, Catholics have about the same chance to become holy as kids without schooling have to get into medical school or athletes without coaching have to make the NFL.

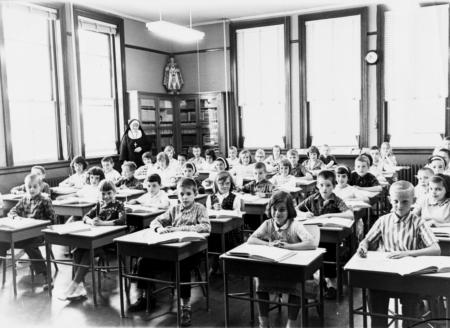

Once upon a time this formation in the Christian life was somewhat provided in Catholic schools by religious teachers who adapted their own formation to the situation of the students. It was buttressed by pious parents and grandparents who considered that their greatest task in life was not to get kids into college but into heaven.

But now, in most places, that formation is no longer being given. Parishes cannot provide adequate training in holiness solely through Sunday Mass homilies and 24 to 30 hours of catechetical instruction a year. Many families struggle to pray together at all, and few impart the spiritual discipline required for their children to become great disciples. It's one of the reasons why the Holy Spirit, I believe, has raised up so many new institutions and movements in recent times to offer concrete spiritual training and fill the gap.

St. John Paul II in 2001 wrote that the training in holiness involves six great pillars: God's grace, prayer, Mass, Confession, listening to God's word and proclaiming it in words and in practice. But even with those pillars, there's a need for help to get the most out of each of these practices. There's also a need to integrate them with a network of other practices in a curriculum of spiritual formation -- similar to the "rules" found in consecrated communities -- designed to help those who follow them grow in holiness day by day.

That program of spiritual formation is generally called a plan of life, which is a game plan of spiritual exercises to help people learn how to fight the good fight, to run the race of life so as to win, and to keep the faith by growing in faith and sharing it (2 Tim 4:7; 1 Cor 9:14). It's a series of practices given to us by the saints and spiritual directors that will help people to translate, for example, a New Year's Resolution to make 2015 a true "year of the Lord" from vague aspiration into reality.

To mark this Year for Consecrated Life, I would like to begin a series of columns on the practices in a typical plan of life that can help us live out our baptismal consecration. They're all things I seek to live by and to train those who come to see me for spiritual direction to live well.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen once said that there are no plateaus in the spiritual life. We're either climbing uphill or sliding downhill; if we're where we were a year ago, we're not the same, but worse. I hope by these columns to pass on some of the tips for all of us to be alpine climbers following Christ up Tabor and Calvary to the heavenly Jerusalem.

- Father Roger J. Landry is a priest of the Diocese of Fall River, Massachusetts, who works for the Holy See’s Permanent Observer Mission to the United Nations.