Knowing the Trinity

Richard of St. Victor, a 12th-century Scottish theologian, is not exactly a household name in 21st-century Christian circles. Truth to tell, I only know of him because of a curious conversation I once had with my friend, the late Richard John Neuhaus, who, as only he could, told me of a friendly discussion he'd had with Rabbi David Novak one summer about the Scotsman's Trinitarian theology, which tried to establish by reason that God must be triune. (We talked about a lot of strange and wondrous things, up there on the cottage deck in the Ottawa Valley.)

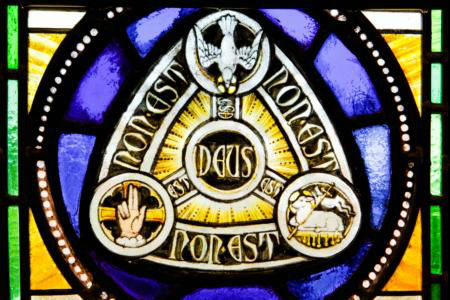

To greatly simplify a complex argument, Richard of St. Victor proposed that perfect love ("God") cannot remain in and by itself; it must direct itself to an equally perfect person ("God the Son"); and the mutual love between those two must have a third person as that to which their common love is directed ("God the Holy Spirit"). Or so the old New Catholic Encyclopedia sums up. Richard of St. Victor's Trinitarian theology didn't attract many followers, and in any case, it somewhat misses the point about the Holy Trinity --which most preachers also tend to do on Trinity Sunday. And that is that we "know" the Triune God, not through abstract argument, but through history.

The first Christians, pious Jews, were strict monotheists. That Christianity came to embrace the doctrine of the Holy Trinity -- indeed, that it put that doctrine at the center of its creed, along with its other key doctrine, the Incarnation -- is one of the great surprises of religious history. The two are linked. And that link is found, not in the abstract speculations of theologians, but in the historical experience of the Christian community.

As biblical scholar Gianfranco Ravasi puts it, the mystery of God's triune inner life is inextricably linked to the love that communicates itself to the world "in a precise historical event, the saving mission of the only-begotten Son." And this, Ravasi continues, is the theme of the nighttime conversation between Jesus and Nicodemus in the third chapter of John's Gospel: Jesus does not offer this pious Israelite, who may also stand for all those who seek the truth about God with a sincere heart, a theological treatise; he offers him a description of what is happening, in history, in himself. A new dialogue between God and humanity has begun, for "God so loved the world that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life" (John 3:16).

So the next time you see some vaguely scruffy brother holding up a "John 3:16" sign at the Super Bowl or World Series, remember that he's offering the world the answer to the speculations of Richard of St. Victor.

We know the Trinity, not because we have reasoned our way to it, but because we have been touched by the Trinity's entry into history. The gift spoken of in John 3:16, Ravasi writes, encompasses not only that which the Father gives (his Son), but also that which the Son, the suffering servant, freely offers in giving himself up to death for the world's salvation. And from that "giving" of the Father and Son comes the outpouring of the Spirit, by whose sevenfold gifts we can come to know, and we are empowered to proclaim, that Jesus, risen from the dead, is indeed Lord, and that through him we have what only God can give the forgiveness of sins.

In strictest theological definition, the Trinity is a "mystery": a truth that can never be fully comprehended by reason, but that can be known to be true in love. That is how the early Christian community came to know the triune nature of the Holy One, the God of Israel: the truth of God-in-himself was discerned in the Christian experience of the Trinitarian love that was poured into the world in the paschal mystery. That is how we can know, however dimly, the truth about God-in-himself today: through the love of God poured into our hearts sacramentally.

George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.

- George Weigel is Distinguished Senior Fellow of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, D.C.