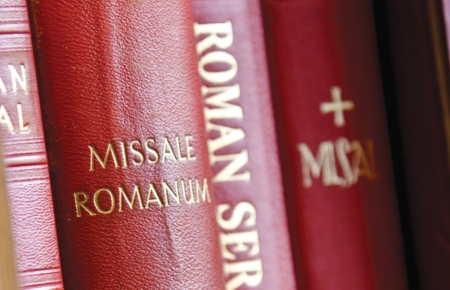

Gained in translation: the challenges of the Roman Missal

A translator is a traitor.

Father Paul Turner, a priest of the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph, knows the saying as an inside joke among those who move words, phrases and meanings from one language to another. He points out that the joke works better in Italian, where the words for traitor and translator are almost the same.

But in any language the phrase points to a greater truth, says Father Turner, a Latin scholar who worked for the International Commission on English in the Liturgy (ICEL) that developed the translation of the new Roman Missal.

"Anytime you translate you are doing your best. But it is nearly impossible to capture all the nuances and bring them into a new language," he says.

At the ICEL commission meetings Father Turner served as a recorder of the proceedings held by 11 bishops from the English-speaking world. Led by Bishop Arthur Roche of Leeds, England, the group reviewed liturgical translations. Along with other scholars, Father Turner, who is also pastor of St. Muchin Church in Cameron, Mo., could raise points about meaning and grammar, but only the bishops voted on the actual approvals.

Sometimes proposed suggestions were inserted into the revised texts; other times suggestions failed to win approval. The group, says Father Turner, was determined that the original Latin of the liturgical texts was faithfully rendered into English as much as possible.

"We want the liturgy to be understood," he says. "But those who pray it have to know that it is the prayer being brought to us by the tradition." The result, for American Catholics who first encounter the Missal, will take some adjustment.

The current translation focuses on rendering the texts understandable to modern English-speakers. The new translation will focus more on keeping the nuances in the original Latin. The result will be the use of some phrases and words that are not normally a part of everyday English discourse.

"It's not that the translation we have is wrong or heretical. But what we gained in fluidity (in English) we lost in nuance (from the Latin)," says Father Turner.

For example: the new translation sometimes uses the word "ineffable" to describe the power of God. Webster's defines the word as anything "incapable of being expressed in words." While not a part of daily English speech -- although Father Turner notes he saw the word in a recent edition of Newsweek -- "it's a great word when you talk about the mystery of God. It is a word that means we are speechless before God." When taken in context, he says, English speakers will become familiar with it for a description of a mysterious quality of God.

Other examples: in the Creed of the new missal, the old translation read that Jesus was "one in being" with the Father. The new translation will describe this relationship as "consubstantial," an English word as close to the original Latin meaning as possible.

"It's an unusual word. But the relationship between Jesus and the Father is unusual and needs a unique word," says Father Turner, who adds that ancient Church councils attempted to define this relationship in a precise a way as possible, and modern English speakers should have the benefit of those insights.

American Catholics routinely recite the Creed each Sunday in which Jesus is described as "born of the Virgin." That phrase, says Father Turner, fails to capture the full nature of Jesus. "Incarnate," the word used in the new translation, is intended to emphasize that at Jesus' conception the divine was present.

It may sound strange at first but, says Father Turner, English-speaking Christians through the ages have recited the Lord's Prayer, with its famous phrase, "hallowed be thy name." The word "hallowed" is rarely used in English anymore, but English speakers reciting the Lord's Prayer easily recognize it in that context. The same should hold true for the terminology in the new missal, says Father Turner.

The ultimate goal will be English-speaking Catholics reciting prayers that more precisely render their original Latin meanings, making the traitor in translation as unobtrusive as possible.

Peter Feureherd is a writer from Rego Park, New York.