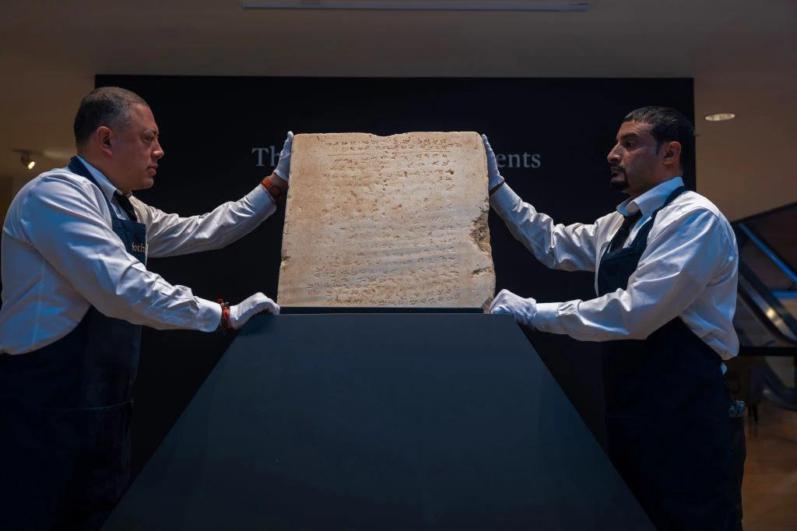

Ten Commandments tablet surpasses estimates at Sotheby's despite authenticity questions

A contentious Ten Commandments tablet has sold at Sotheby's for $5.04 million -- more than twice its high estimate of $2 million.The auction took place on Wednesday in New York City.

Promoted by the auction house as "the earliest surviving inscribed tablet of the Ten Commandments" and purportedly dating to the late Roman-Byzantine era, the marble slab drew intense scrutiny ahead of the sale, with scholars disputing its provenance and authenticity.

According to Sotheby's, a local worker discovered the roughly 115-pound artifact in 1913 during railway construction in what is now Israel. Unaware of its significance, he reportedly used it as a threshold stone for decades.

It was only in 1943, when scholar Jacob Kaplan acquired the tablet, that its potential importance as a Samaritan Decalogue emerged. Sotheby's relied partly on this narrative and the object's wear as indicators of its antiquity.

Some experts remained unconvinced.

"It may or may not be ancient," said Christopher Rollston, the chairman of the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations at George Washington University in an interview with CNA.

"Sotheby's has not done its due diligence with this piece, and I find that to be deeply problematic." Rollston argued that while Sotheby's cites wear patterns as evidence of age, decades of use as a doorway threshold alone could account for the stone's abrasion.

In a recent blog post for The Times of Israel, Rollston also noted that the tablet omits the commandment forbidding the misuse of God's name -- a precept included in the Samaritan Pentateuch.

He suggested that such deviations might be intentional "surprising content" introduced by forgers to stoke interest. "For 150 years, and indeed much longer than that...forgers have been producing fake inscriptions with surprising content," Rollston wrote in the blog.

Sotheby's defended its process. "Sotheby's regularly undertakes due diligence procedures to authenticate and determine the provenance of property prior to accepting it for sale, and the research into this property was no different," a spokesperson said before the sale.

The house emphasized that the tablet "was also seen by scholars who had the opportunity to inspect it first-hand" and has appeared in scholarly publications since 1947 without prior challenges to its authenticity.

The strong price underscores the ongoing tension between market demand for rare antiquities and persistent legal, ethical, and academic debates about how such objects are vetted.

"Auction houses don't have any specific legal obligations to verify authenticity and provenance," said Patty Gerstenblith, Distinguished Research Professor of Law and Director of the Center for Art, Museum & Cultural Heritage Law at DePaul University. "The auction house typically owes a fiduciary obligation to the consignor, not the buyer."

If doubts arise after a sale, buyers face hurdles. "If the artifact turns out not to be authentic or not to have lawful provenance, the purchaser may be able to sue the auction house," Gerstenblith said, noting that such claims often hinge on whether the auction house's assertions amounted to a warranty or were made fraudulently.

While the $5.04 million result indicates robust interest in this piece of purported biblical heritage, the scholarly skepticism voiced by experts like Rollston suggests the tablet's true legacy -- and its place in the historical record -- may remain the subject of vigorous debate.