Supreme Knight examines legacy of JFK inauguration speech

BOSTON -- "Upon what can we rely? ... In what can we find hope for the future? The answer, I believe, lies ultimately in the very principles which we honor tonight -- the principles of our religious heritage," then-Sen. John F. Kennedy told his brother Knights of Columbus in 1958. The event, held in Boston, commemorated the 50th anniversary of Pere Marquette Council.

He went on to say that the Catholic faith teaches self-discipline, which enables sacrifice and determination.

Some Catholics have often criticized President Kennedy for words spoken at a different event in Texas two years later. They have said he put aside his faith while trying to attain the nation's highest office.

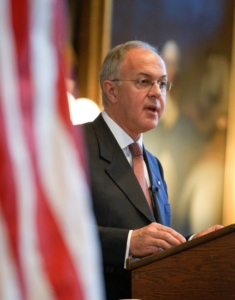

Carl A. Anderson, supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus, spoke about JFK at Faneuil Hall on April 7. The knights, who sponsored the talk, are the world's largest fraternal service organization with 1.8 million members.

Anderson's Boston remarks focused on Kennedy's inaugural address, given 50 years ago. According to a poll commissioned by the knights in January, 9 out of 10 Americans still see importance in that speech.

"Few presidential speeches in our history have so clearly presented the spirit of our nation's historical, philosophical and moral foundation," said Anderson.

In it, Kennedy challenged Americans with a moral imperative. His most famous words were, "Ask not what your country can do for you -- ask what you can do for your country."

Anderson asserted that this principle "goes to the heart of who we are as citizens and goes to the heart of who we are as a people" speaking "not only of the relationship between the governed and the government, it speaks also of the relationship between each of us and our neighbors."

"I believe the simple answer is that we ought to strive to make our great country even greater," Anderson said in answer to the famous question.

He added that Americans must be faithful citizens who exercise their rights and duties, and they must reach out to their neighbors in "a spirit of charity."

But these principles were not meant to be a reinvention of the United States. Rather, they were a restatement of principles that underpin our rights as Americans, Anderson said.

Like Kennedy, the forefathers believed that the rights of man come, not from the generosity of the state, but from the hand of God. The Declaration of Independence states that men are "endowed by their Creator" with the rights of "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

The signers of the Declaration held that the "rights cited in their claim were not simply matters of opinion or even of belief."

More importantly, they were and are, "God-given rights that could not be taken away by any person or any government. These rights are self-evident and those words were unanimously adopted. On this moral foundation, America staked its claim for liberty."

The belief in God-given rights makes America's revolution different from another revolution that occurred in the 18th century. The French who fought for independence believed that rights came from the state and that religious belief was an obstacle to liberty, he said.

Anderson called Kennedy's inaugural words a "timely reminder" of our fundamental rights. He also affirmed the dignity of every human person and encouraged Americans to be their neighbors' keeper.

"Kennedy admonished us that if a free society cannot help the many who are poor, it cannot save the few who are rich," he said.

According to Anderson, Kennedy also presented the Judeo-Christian heritage "in a way that Americans -- Catholics and non-Catholics alike -- could agree with" believing that he could "reaffirm America's moral and spiritual heritage without imposing his Catholic beliefs, and Americans, for their part, overwhelmingly approved of Kennedy's speech."

American Catholics seek neither theocracy nor secularism but a moral way forward for our country, informed by the values that have guided the nation. The challenge is to make Christianity a positive force in the political world without it being turned into a political instrument, he added.

"We are called to transform society. Our job is not an easy one," he said. "We must have the same values in the public square that we have at church."

Attempts to remove religious values threaten to "sever our country from its historical roots" and "place its future in peril."

"The belief that our rights to life and liberty are from the Creator, compel millions of our fellow citizens to question how the state can supercede that right with legalized abortion or euthanasia, and millions more question how we can believe that God is the foundation of our rights and remain silent as others attempt to rid the public square of religious values in order to fashion a completely secular society," he said.

Anthony Cusack, a seminarian at St. John's Seminary in Brighton, told The Pilot that Anderson's talk brought faith and politics together in a positive way. Once he is ordained, he expects to teach about abortion and same-sex marriage and to encounter arguments about the separation of church and state.

"Preaching, for us, is very key because that's how we communicate to people that as, not only citizens but as Catholic citizens, these are the issues we need to be aware of and this is how our faith needs to impact those decisions," he said.