Readers should brace themselves for painful history of church racism

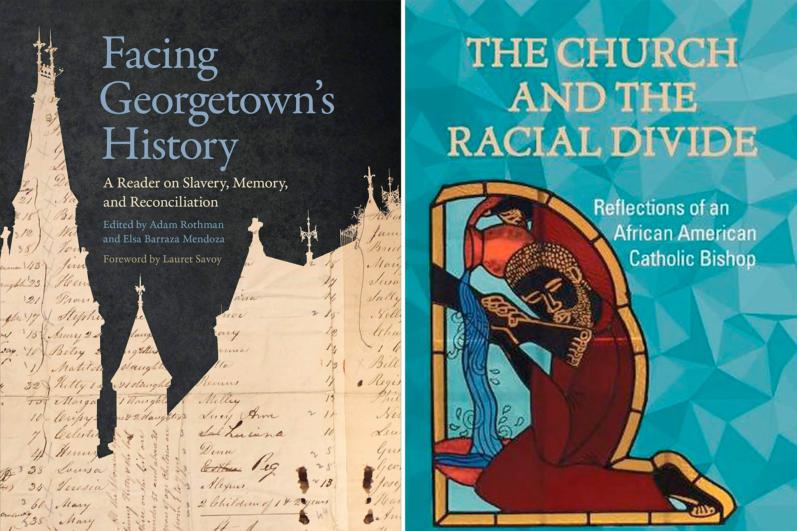

"Facing Georgetown's History: A Reader on Slavery, Memory and Reconciliation," edited by Adam Rothman & Elsa Barraza Mendoza. Georgetown University Press (Washington, 2021). 360 pp., $29.95.

"The Church and the Racial Divide: Reflections of an African American Catholic Bishop" by retired Bishop Edward K. Braxton of Belleville, Illinois. Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York, 2021). 248 pp., $26.

Readers should be -- but probably can't be -- mentally, emotionally and spiritually prepared to absorb what they will read in "Facing Georgetown's History." Given that such preparation might not be possible, they should come with open minds and hearts in order to internalize what is presented.

"Facing Georgetown's History" is an extensive compilation of material related to the university's Gospel-less roots, articulated by Adam Rothman in the book's introduction:

"Georgetown was founded in 1789 by a slave-holding Catholic elite in the new United States. The school anchored a web of plantations, churches and schools managed by the Maryland Jesuits and their proxies. ... The Maryland Jesuits' infamous sale of their human property -- 272 children, women and men known as the GU272 who lived and worked on plantations across Maryland -- helped to pull the struggling school out of a burdensome debt in 1838. The leaders who orchestrated the sale had few qualms about it."

The first part delves extensively into the history through four scholarly essays and more than a dozen documents specifically related to Catholic laity, Jesuits, Georgetown and slavery.

All of the essays are eye-opening, well researched and provide an education in Catholic history absent from college and other classrooms as recently as a decade ago. The most powerful of the writing is Elsa Barraza Mendoza's "Catholic Slave Ownership and the Development of Georgetown University's Slave Hiring System, 1792-1862."

Catholic readers will wonder what the slaveholders were thinking and, more importantly, how and why they failed in their practice of Jesus' instruction to love one another. As with the other essays in this section, it is painful to read about the lack of Gospel witness.

Among the remaining documents of this section are descriptions of "property" sales, e.g., a 1717 deed in which 15 "Negro servants" are listed with bedding, cattle and "church stuff."

Another chapter includes an 1835 speech by Jesuit Father James Ryder, a Georgetown professor and future president of the school, in which he criticizes abolitionism and seconds six resolutions made by members of the Catholic community of Richmond, Virginia, which became the capital of the Confederacy 16 years later.

One resolution read: "That while we view slavery in the abstract as an evil, we hold it to be our first duty as Christians and citizens, to support the civil institutions of our country."

The second part of the book, titled "Memory and Reconciliation," begins with three scholarly essays, the most powerful and moving of which is Ta-Nehisi Coates' "The Case for Reparations." Given the political rhetoric that reparations stoke, this is a must-read history lesson inside and outside the context of the Georgetown story.

If the first part of the book evokes despair, the second part helps one recover from it. Pieces written by descendants of the GU272 should make readers think. "A New Path for Atonement," an essay by Marc Parry, offers hope for resolution of what to do and the reconciliation in the book's title that must be a part of that resolution.

"The Church and the Racial Divide" is a collection of writings by Bishop Edward K. Braxton, who headed the Diocese of Belleville, Illinois, from 2005 until his retirement in 2020. Each is preceded by a note placing the piece, be it an address, column or pastoral letter, in the context of the time at which it was written.

The bishop's words are enlightening. In the preface, in which he notes that through many years of positive and negative experiences he has become "more and more ‘woke,'" he adds, "I have found my own voice." It's a voice that Catholics need to hear.

His 24-page introduction sets the tone for what follows as he recalls his family's history and events in his own life. Bishop Braxton's writing touches on a variety of subjects, e.g., the Museum of African American History and Culture, Black Lives Matter, cultural divide, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Emmett Till, Father Augustus Tolton and Black theology.

He frequently mentions the U.S. bishops' 1979 pastoral letter on racism, "Brothers and Sisters to Us." He quotes it at length in a chapter titled "Black Catholics in America," in which he notes, "Some may be surprised at how strong these recommendations are, and may ask: ‘What more can the church say? Where do we go from here?' There is no need to say more. The need is to do what we have said. ... I fear many Black and white Catholics cannot go forward until they go back to the council (Vatican II) documents and to this landmark pastoral letter and ponder their teachings."

At several points in the book, including the conclusion of the introduction, Bishop Braxton writes, "Listen! Learn! Think! Pray! Act!" Those words are fitting advice as to how -- and why -- one should read it.

- - -

Also of interest: "A White Catholic's Guide to Racism and Privilege" by Daniel P. Horan, OFM. Ave Maria Press (Notre Dame, Indiana, 2021). 224 pp., $17.95.

"Justice Rising: Robert Kennedy's America in Black and White" by Patricia Sullivan. Harvard University Press (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2021). 544 pp., $39.95.

"Black Catholic Studies Reader: History and Theology," edited by David J. Endres. Catholic University of America Press (Washington, 2021). 180 pp., $29.95.

- - -

Olszewski is the editor of The Catholic Virginian, biweekly publication of the Diocese of Richmond, Virginia.