What the Supreme Court did (and didn't do) to religious freedom

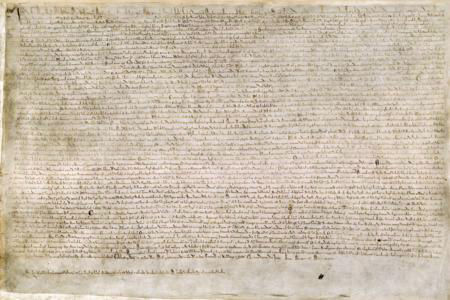

On July 1, Magna Carta, in one of its four surviving original copies, the one from Lincoln Cathedral, began a U.S. Tour with an exhibit at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts. The legal document, dating from June 15, 1215 -- which means it's celebrating its eight-hundredth anniversary -- begins and ends with King John guaranteeing "that the English church shall be free," with its rights undiminished and its liberties unimpaired. It is one of the few provisions of Magna Carta that still remains on the English statute books.

On July 6, I visited the Magna Carta, and was struck by the coincidence that July 6 is also the anniversary of the martyrdom of Thomas More, once Lord Chancellor of England, who was executed for treason because he would not take an oath prescribed by Parliament that made Henry VIII Supreme Head of the Church in England. At his trial, he was overruled in his claim that the Act of Supremacy violated Magna Carta and the King's coronation oath. After all, the provision of Magna Carta originally meant freedom of the Church from royal control. Which goes to show that religious freedom, however admirable in theory, can rather easily be disregarded in practice.

Admittedly, there are close cases. The recent Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood Specialties cases, however, released by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 30, the last day of its term, should not have been among them. The case was decided 5-4, however, with Justice Samuel Alito writing the majority opinion, and Justice Anthony Kennedy, in concurrence, once again providing the swing vote. The Court's four liberals, led by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, dissented.

The cases involved claims by closely-held family-run businesses that the requirement promulgated by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to implement The Affordable Healthcare Act (Obamacare), that they had to provide free coverage for their employees of four types of contraceptives that can cause abortion. While the regulations required the companies to provide free-of-charge 20 different types of contraceptives to women, these companies, owned and run by Protestants, did not object to contraception as such, but only those four types of contraceptives that have a feature that would prevent implantation of a fertilized embryo into the woman's uterus and thus cause an abortion.

Like so much involving the Affordable Healthcare Act, the cause became politicized. There's an interesting contrast with the case the Court decided unanimously the week prior, McCullen v. Coakley, in which the Supreme Court struck down a Massachusetts buffer zone in front of abortion clinics, because it violated freedom of speech. So in a case that also involved abortion and the First Amendment, the Court was capable of speaking with one voice, legally rather than politically.

In Hobby Lobby, the Court ruled that a federal law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), applied to the case, and that it covered "any exercise of religion, whether or not compelled by, or central to, a system of religious belief." The only question that government could consider was not the truth or reasonableness or centrality of the religious belief, but only whether the belief were sincere, which was not doubted in the case of these companies. Interestingly, RFRA had passed in 1993 by overwhelming majorities of both houses of Congress. This is because religious freedom, like free speech, is a vital part of our legal heritage and until recently, viewed as axiomatic.

The Court said that companies were legal persons within the meaning of RFRA, an unexceptional view dating back to the Middle Ages, when the Church, as the Body or Corpus of Christ, was viewed as a corporation with legal personality. Citing William Blackstone, the authoritative expounder of the common law at the time of the American founding, the Court recognized that there were two types of corporations, ecclesiastical and lay, and that lay corporations could also have eleemosynary and religious purposes. (The amicus brief I filed in support of Hobby Lobby for four non-profit corporations made the same point, also citing Blackstone.)

Because of the political firestorm that erupted several years ago when the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in favor of corporate free-speech rights in the Citizens United case, which President Obama had denounced in his State of the Union address, this question of the First Amendment rights of corporations, and specifically whether for-profit corporations were legal persons, has become politicized. Even so, two of the liberal justices, Justice Stephen Breyer and Justice Elena Kagan, did not join that part of Ginsburg's dissent that said that for-profit corporations were not legal persons.

As Justice Alito pointed out for the majority, "it is important to keep in mind that the purpose of this fiction [that corporations are legal 'persons'] is to provide protection for human beings. A corporation is simply a form of organizations used by human beings to achieve desired ends...When rights, whether constitutional or statutory, are extended to corporations, the purpose is to protect the rights of these people."

Since corporations, or at least closely-held family-run companies, can claim to exercise religion, the law requires that if their religious exercise is substantially burdened, then the government must show both that it is seeking to achieve compelling government interests, and that it is doing so in the least religiously restrictive way possible: a demanding ends and means test. If the government passes the test, the matter belongs to Caesar. If not, then it belongs to God and the religious conscience of believers.

Justice Kennedy concurred by saying that while free contraceptives for women was a compelling government interest, the government had a lesser restrictive alternative in that it could either provide the contraceptive coverage itself or extend the accommodation HHS was already giving religions non-profits, to for-profit closely-held companies with religious objections. Because he was the swing vote, the majority had to assume for the sake of argument that there was a compelling interest in free contraceptives, though the prevalence of exceptions in the regulation for grandfathered companies, companies with less than 50 employees, and Churches and other religious organizations, makes that very questionable. If it's so important to government, then why is it handing out exemptions like party favors to all those except for-profit companies with religious objections?

And so the majority ruled that the huge fines the families faced for not covering the abortifacient contraceptives did constitute a substantial burden on their religious practice, and that even assuming a compelling government interest in support of the regulation, the government had failed to show that cost-free access to these contraceptives was the least-restrictive means of achieving its desired goal. Either the government could assume the cost itself, or extend the accommodation it already was giving non-profit employers with religious objections to the mandate.

The Court went on to say that its ruling did not necessarily apply to vaccinations or blood transfusions, nor did it provide a shield to employers illegally discriminating on religious grounds. Those matters will have to wait for another day.

It did not take long, however, for the plot to thicken. On July 3 the Supreme Court issued an order in the case of Wheaton College v. Burwell, Secretary of HHS, granting an emergency injunction to the Protestant college, which had religious objections to filling out the bureaucratic form whereby the school notified its insurer of the obligation to provide full contraceptive coverage. The Court said that "the applicant has already notified the government that it meets the requirements for exemption from the contraceptive coverage on religious grounds." That was sufficient, at least pending full lower court review of the merits. The Court said "this order should not be construed as an expression of the Court's view on the merits."

Even though Justice Sonia Sotomayor had issued a similar emergency injunction protecting the Little Sisters of the Poor from the contraceptive mandate on New Year's Eve, she now wrote a dissent joined in by the other female justices, Ginsburg and Kagan. (Interestingly, they were not joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, who had dissented in the Hobby Lobby case.) While the Court here divided along gender lines, it did not divide along political lines or religious ones (Breyer is Jewish, and Sotomayor is Catholic.)

Justice Sotomayor claimed that this emergency injunction was distinguishable from the one she granted, and the full Court confirmed, in the Little Sisters of the Poor case, which is still pending. But more tellingly, she claimed that filling out the form that notified the insurer was not a substantial burden on religious exercise, and that it was the least restrictive means of achieving the government's compelling interest. She also said that the Court seemed to be back-tracking on the viability of the "accommodation" that just days earlier they had said was a lesser restrictive alternative for religious non-profits.

I was struck by how over-the-top much reaction to the Hobby Lobby case was, as if, all of a sudden, applying a law intended to protect religious freedom to the facts of a particular case were a threat to civil liberties. Justice Ginsburg, for example, calls it a "decision of startling breadth," and demonstrates that she is opposed to RFRA, in spite of the careful hedging of the majority's opinion. In front of the Supreme Court building the Monday that the decision was issued, there were contending demonstrators. The pro-government contingent had a slogan, "My birth control is none of your business." Precisely. That's what the companies were saying: Get your hand out of my pocket.

As James Taranto of the Wall Street Journal pointed out, the Freedom from Religion Foundation's full-page ad in the New York Times asserted, quoting retired Justice John Paul Stevens, "Corporations have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires." Taranto retorted: "Then shut up." But of course corporations, like the people who comprise them, can be hypocritical too.

Dwight G. Duncan is professor at UMass School of Law Dartmouth. He holds degrees in both civil and canon law.

- Dwight G. Duncan is professor at UMass School of Law Dartmouth. He holds degrees in both civil and canon law.