Cleveland Catholic church's 'alfombras' take shape during Holy Week

CLEVELAND (CNS) -- During Holy Week in her native El Salvador, Thelma Chavez, 60, would go and watch the elaborate Holy Week sawdust "alfombras," or carpets, being prepared in time for Good Friday evening.

This year for the first time in her life, she participated in the creation of the carpets at her parish church, Sagrada Familia, in Cleveland. It is the fourth year the parish, largely made up of Hispanic members, is following this Easter tradition.

"I remember when I was a child we would go see the 'alfombras' and they were so beautiful. They would start to prepare them during Holy Week," said Chavez, who moved to Cleveland two years ago. "It made me so happy to see the church doing it here too. Now what I never did in my own country I am doing here."

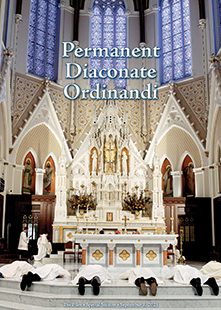

Following a Palm Sunday community lunch in the church auditorium, chairs and tables were pushed aside and the floor scrupulously swept before sheets of plastic were put down. This is where the alfombras would be made throughout the week.

A tradition which brought to the Americas possibly by the Spanish, the alfombras are a Holy Week custom in numerous countries in Latin America including Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras and Peru.

Traditionally made with colored sawdust, today some are made using colored sand or salt. In Peru, the carpets are made of flower petals. Each follow their own traditions as to when the work on the alfombras begin, but all are made outside in public areas and must be completed before the Good Friday procession that will pass over the carpets, destroying them.

The whole process is sacrificial in nature, noted parish priest Father Robert Reidy, who helped begin the tradition in Cleveland 25 years ago when he was a pastor at Sacred Heart Chapel in Lorain.

Upon returning from service in Cleveland's diocesan mission in El Salvador, he wanted to incorporate the tradition into his new parish as an act of sacrifice to end Lent. He and parishioner Roberto Alejandro Santiago, who needed an Eagle Scout project, initiated the project four years ago.

"It is a way to express your faith through art and to know it will be sacrificed on Good Friday when we will walk through it. The first year people didn't understand why we were going to destroy them after all that hard work," Father Reidy told Catholic News Service.

The tradition was adapted to the Cleveland climate, he said, and so the alfombras are made inside. Even non-Hispanic members of the parish have become involved in making alfombras, he said.

"It brings me so much joy to see how far we have come as a community. You can really feel (Jesus') presence here. You have the church as a whole coming in on this," said Santiago, now 16.

People bring in their designs in on a flash drive. Using a computer and a projector, the image is shown on a wall where a plastic sheet has been placed, Designs are traced on to the sheet, before it is placed on the floor to be used as a template.

The first year fewer than 20 alfombras were made, this year they were close to making 50.

Organizers needed to figure out the logistics for the growing number of participants, including community groups such as the Cleveland Rape Crisis Center's Hogar Consuelo comprehensive outreach program for the Hispanic community. The center sees the alfombras as way of connecting to the community as well as creating an awareness of their program.

"This tradition is in remembrance of the sacrifice which Jesus made for us on his way to Calvary. Come Good Friday our procession will leave the church (sanctuary) and we will walk all over the alfombras. It is a sacrifice we make. We spent the time to make these and it is physically taxing to sit, kneeling, on these hard floors," said his father, Robert Santiago Jr., 52. "We are remembering Jesus when he went on his path (carrying the cross for us)."

People are greatly impacted when they walk over the beautiful alfombras, physically feeling his presence and his sacrifice as they destroy their own hard work, he said. Many begin to cry, added Santiago.

"It makes you feel humble how it brings all the people together in homage of our Lord. It helps us learn how different communities within the church think and look at their traditions," said Benny Ortiz, 61. "We don't have to be here but we choose to be here because we care about this tradition."